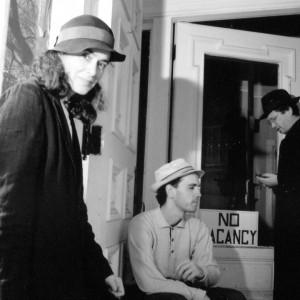

Talk about woodshedding: The Howling Turbines perform in the woodpile for a fundraiser at Flatbread Company in 2002. In addition to being relegated to the woodpile, we weren’t allowed to use a PA — heaven forfend that we should interrupt the joyous shrieking of childish bliss at this popular family restaurant. Jeff Stanton photo and montage.

The merry-go-round is beginning to slow now

Have I stayed too long at the fair?

The music has stopped and the children must go now

Have I stayed too long at the fair?

— Billy Barnes

Avoid the sad words! Instead, spend freely at the Bandcamp Howling Turbines store!

With our host Bob Gallagher shown at upper left, the Howling Turbines perform at a party circa 2002. Photo by Jeff Stanton.

As I look back, the last years of the Howling Turbines, from 2001 to 2004, had a winter-sunset quality.

Of course, it didn’t seem that way to me at the time. Instead, it felt like business as usual, right up to the end. But now, recalling those years and listening to recordings from then, I get a distinct sense of streetlights flickering on, the sky going briefly garish then dark, and crows flocking home to roost.

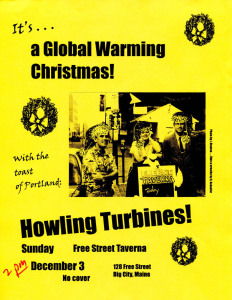

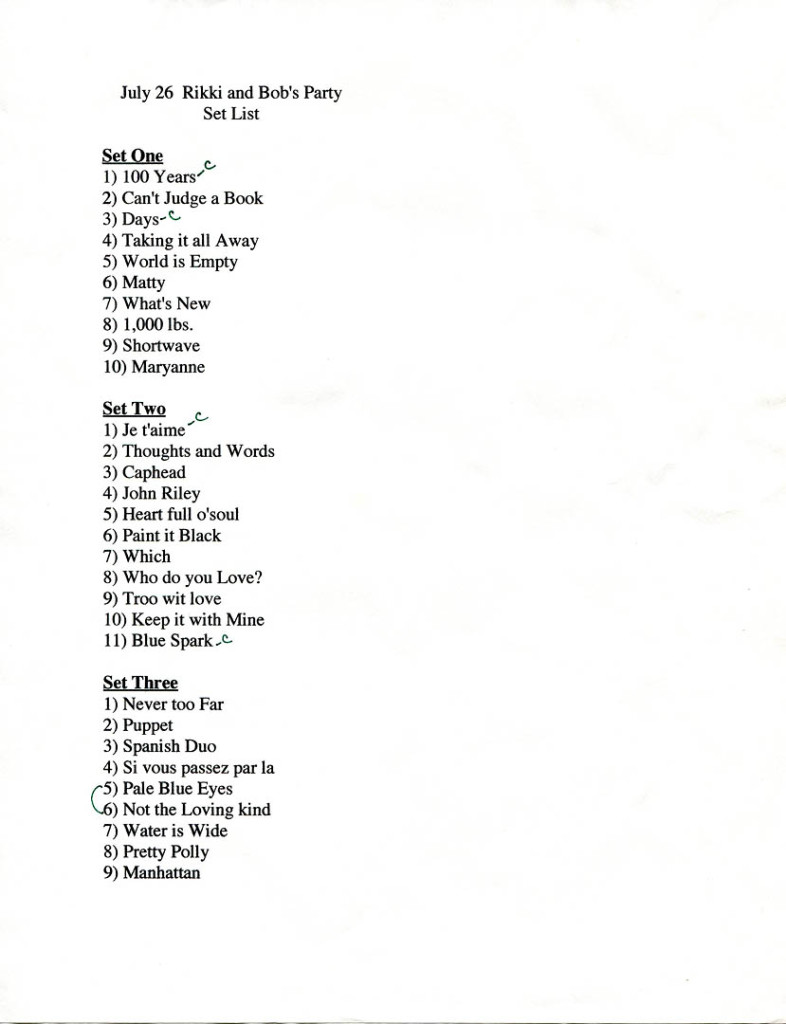

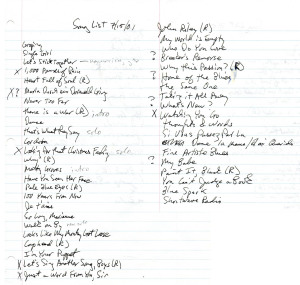

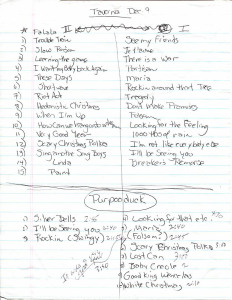

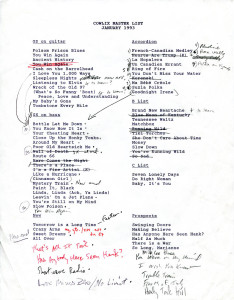

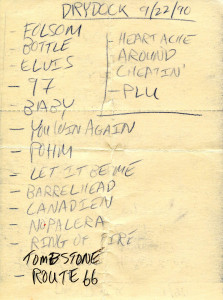

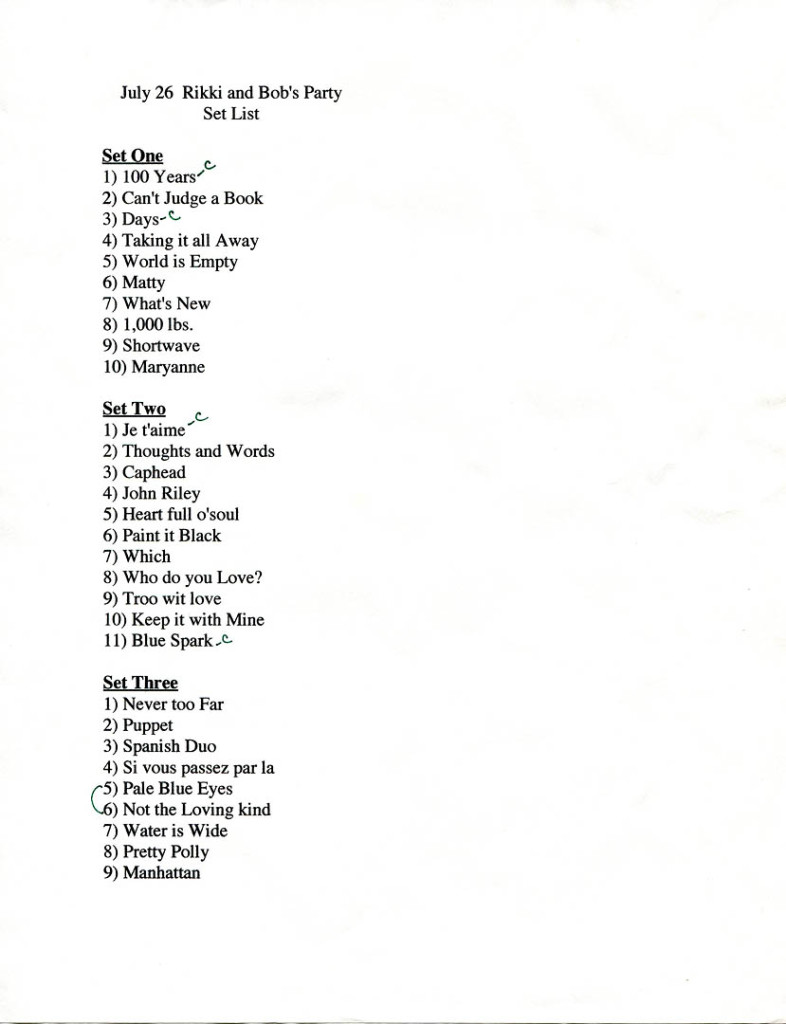

The Turbines’ setlist for the last party we played at Rikki and Bob Gallagher’s house, in 2003. We set up on the back deck, rain began and we tore it all down, the rain stopped and we set it all up again. Hardly anyone attended. Hubley Archives.

The Howling Turbines continued to rehearse and, very occasionally, to perform. We bought more instruments to make more sounds, although there was less energy behind the sounds. The tempos slowed but we still found new reservoirs of sophistication, feeling and even beauty.

Our demise was not dramatic. In fact, though the Turbines’ music could be quite dramatic, or at least loud and then soft, there was never much personal drama among the three of us. We came together as musical veterans who shared a long history, solid affection and a lot of musical taste.

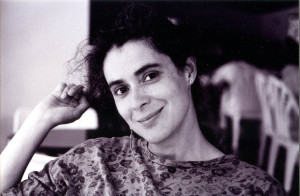

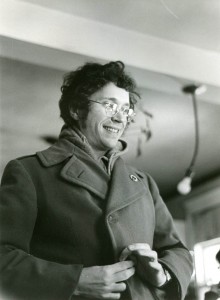

Howling Turbines bassist Gretchen Schaefer, shown in Rikki and Bob Gallagher’s backyard in Westbrook during one of the four Gallagher parties we played. Photo by Jeff Stanton.

Drummer Ken Reynolds and I started playing together in the late 1970s. Bassist Gretchen Schaefer, my wife since 2002, entered the picture in 1981 during the days of Ken’s and my band the Fashion Jungle, and she had performed with me in the Cowlix and Boarders.

In short, we were congenial. The Turbines’ end wasn’t a big knife festival. It was more like death from a thousand cuts.

Gretchen and Doug during a Gallagher party. Photo by Jeff Stanton (image distortion by inkjet printer)

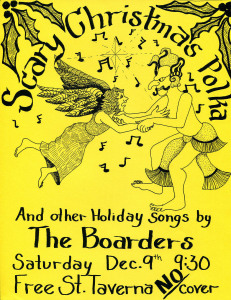

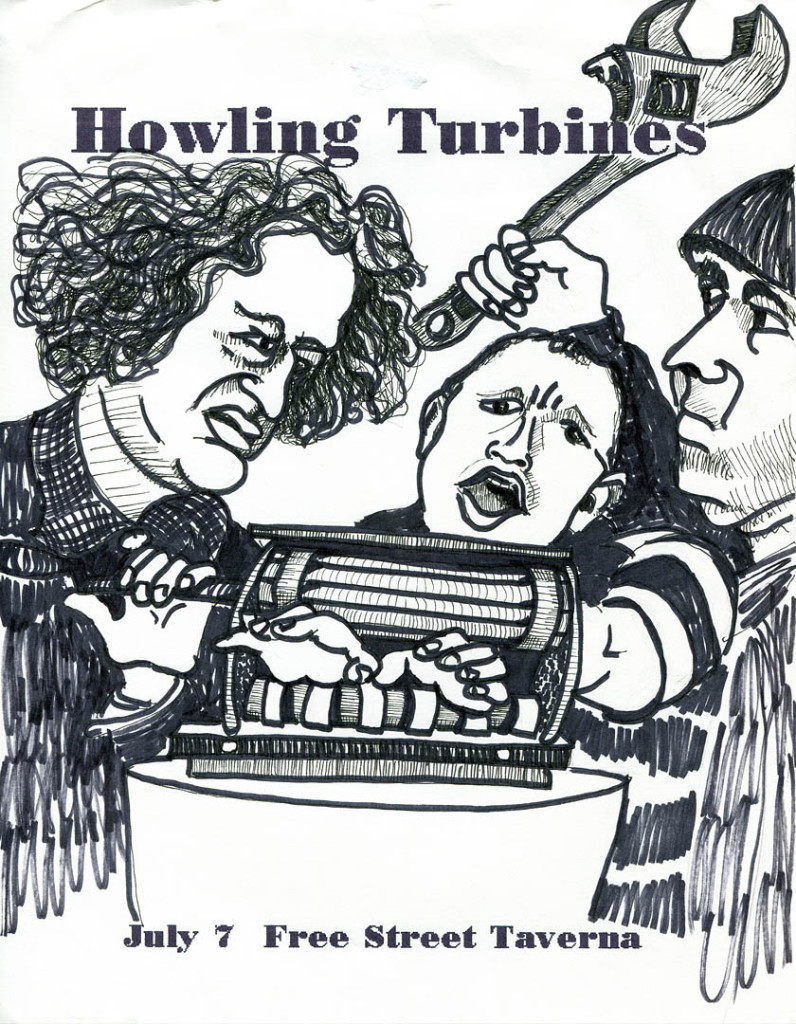

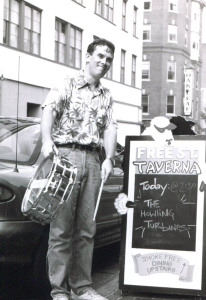

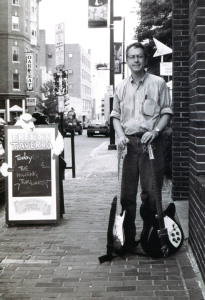

Never energetic about bird-dogging gigs (perfect: a band of introverts), we lost our one steady venue in 2002 when Peter Kostopoulos sold the Free Street Taverna. I don’t remember if we tried to get bookings from the Taverna’s next owner, but in any event we never played there again. The sale of that bohemian watering hole was the end of an era, and not just for the Turbines.

So thereafter performances were even less frequent than before. In fact, it was mainly because of two friends, Gretchen’s colleague Rikki Gallagher and her husband Bob, who several times invited us to play at their parties, that we had any gigs at all during those last years. (We did have the inestimable honor of playing acoustically in the woodpile of a hangar-like Portland pizza place that wouldn’t let us use any P.A., so, sonically at least, we might as well not

even have been there at all.)

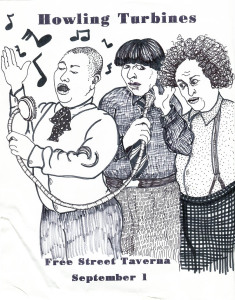

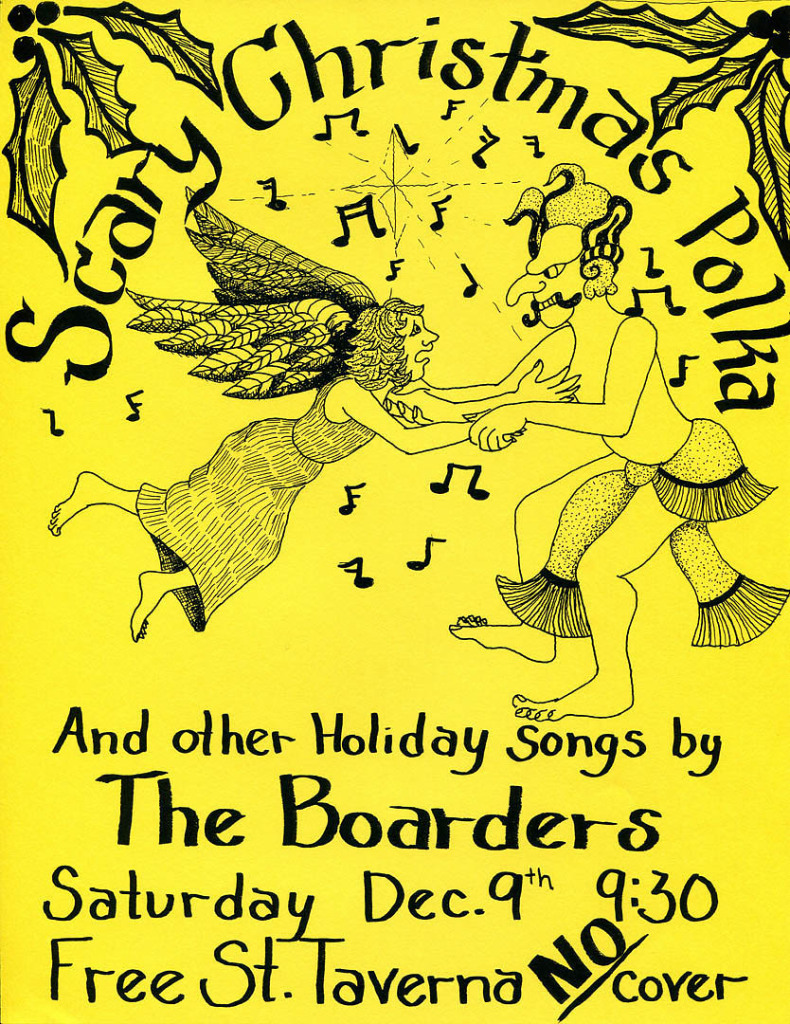

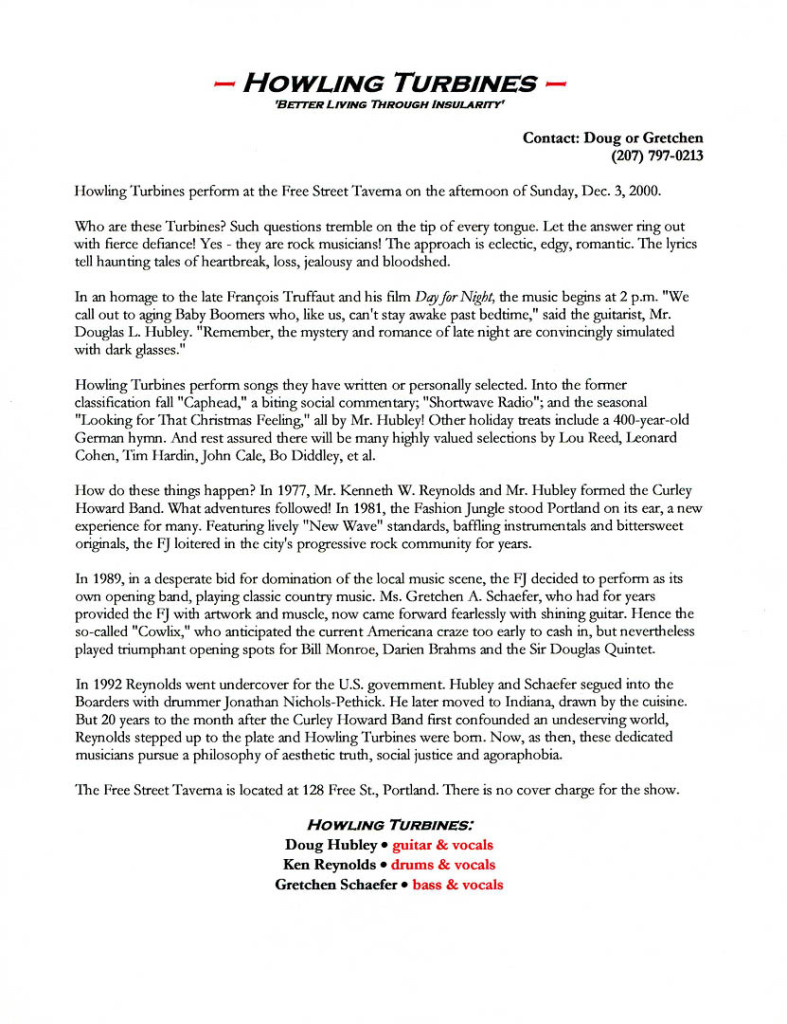

It’s a different side of Larry in one of Gretchen Schaefer’s Howling Turbines posters based on Three Stooges publicity stills. And here I thought he was the nicest of the bunch. Hubley Archives.

And the Gallaghers’ invitations led to a fruitful new direction for the Turbines. Although we twice played electric in the Gallaghers’ back yard, we also performed indoors for them in the winter. This meant going acoustic — and we liked it.

The memories of those performances in the Gallaghers’ living rooms, one in Westbook and one in Raymond, remain vivid: so satisfying, so musical, such great communication among the Howling Turbines.

For those dates, Gretchen played a Martin acoustic bass guitar, I played the Gibson J-100 and Ken alternated among his new djembe, a very minimal kit played with brushes, and bongo drums that I had given Gretchen for Christmas an eternity ago, in the 1980s. The musical communication among the three of us seemed to gain both nuance and depth. We couldn’t make the big sound or the big beat, but we seemed to gain capability in other ways. Suddenly we were branching out in new directions: going deeper into torch music, deeper into folk and world music.

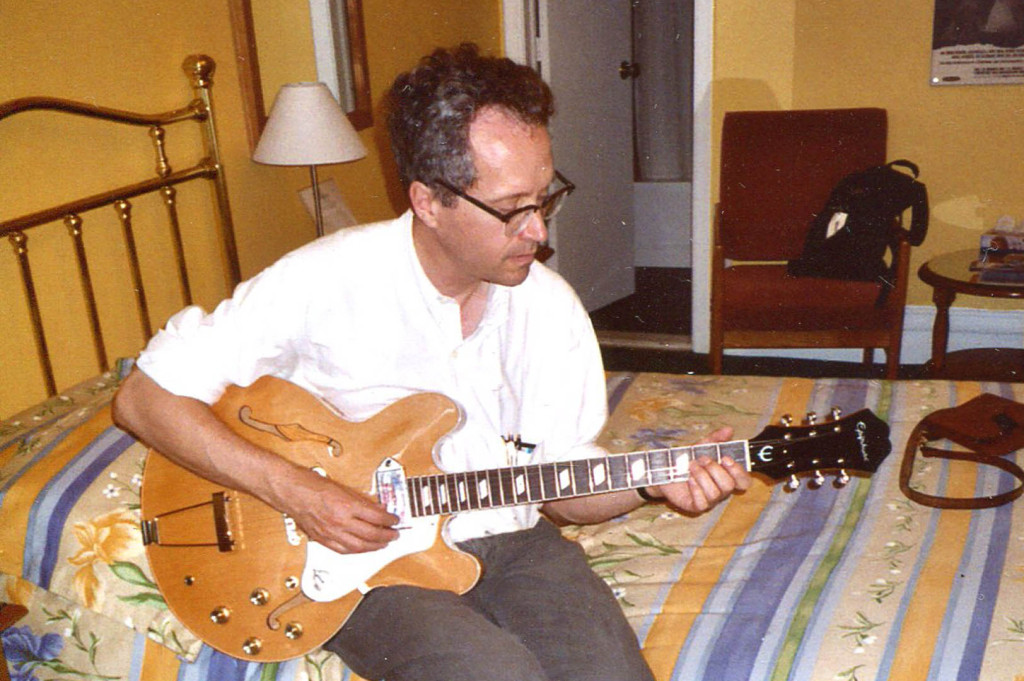

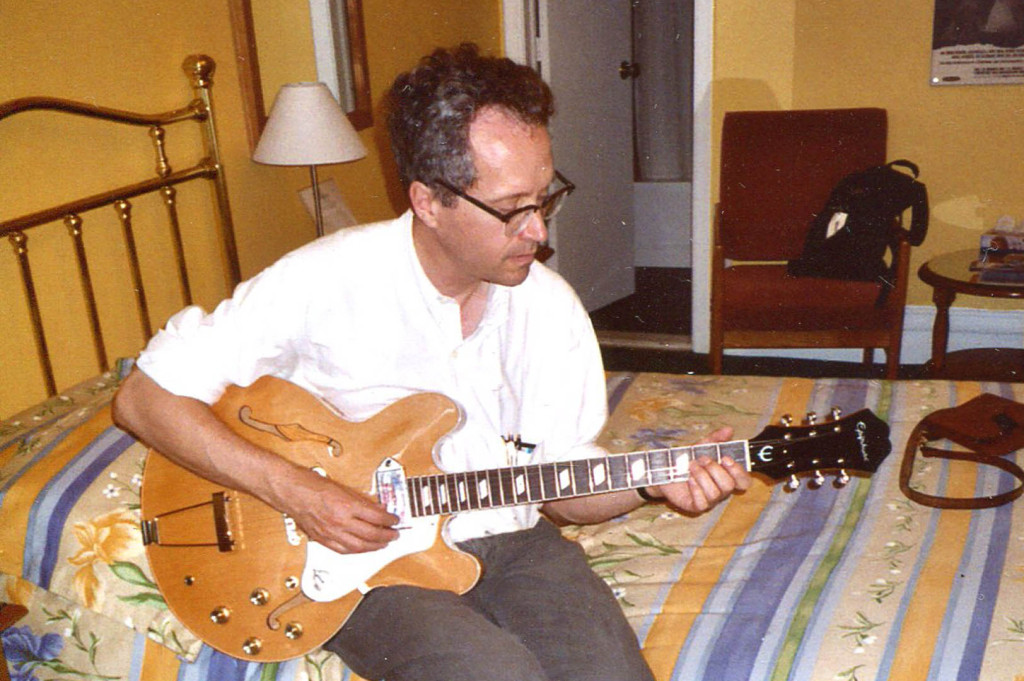

The Epiphone Casino in a hotel in Montreal, where I bought it at a shop near the Jean Talon market. Gretchen Schaefer photo/Hubley Archives.

The djembe, which Ken got around 2000, was transformative. This hand drum opened to us the extensive bazaar of world variations on the ole two-beat. In both acoustic and electric modes, we glommed up a gratifyingly new, to us, diversity of rhythms that was a welcome added dimension to the metallic Turbines sound.

The Excelsior, aka Bluebell, purchased at Accordion-O-Rama in New York City. Photo by Gretchen Schaefer/Hubley Archives.

I got a couple of new instruments in those years, too. In summer 2002, at a store near the Jean Talon market in Montreal, I succumbed to the longtime desire to own an Epiphone Casino. This specimen was blond and, unlike other Casinos I had tried, would stay in tune for the duration of an entire song. At the time they were priced at about US$550 and C$550, and the Canadian dollar was much cheaper, so how could I resist?

That same year, in November, I made my second purchase at the legendary Accordion-O-Rama, located at the time in Manhattan (and now in South Amboy, New Jersey). Gretchen was attending a conference, and since I was footloose and fancy-free, it was only natural that my first thought was to buy a new accordion.

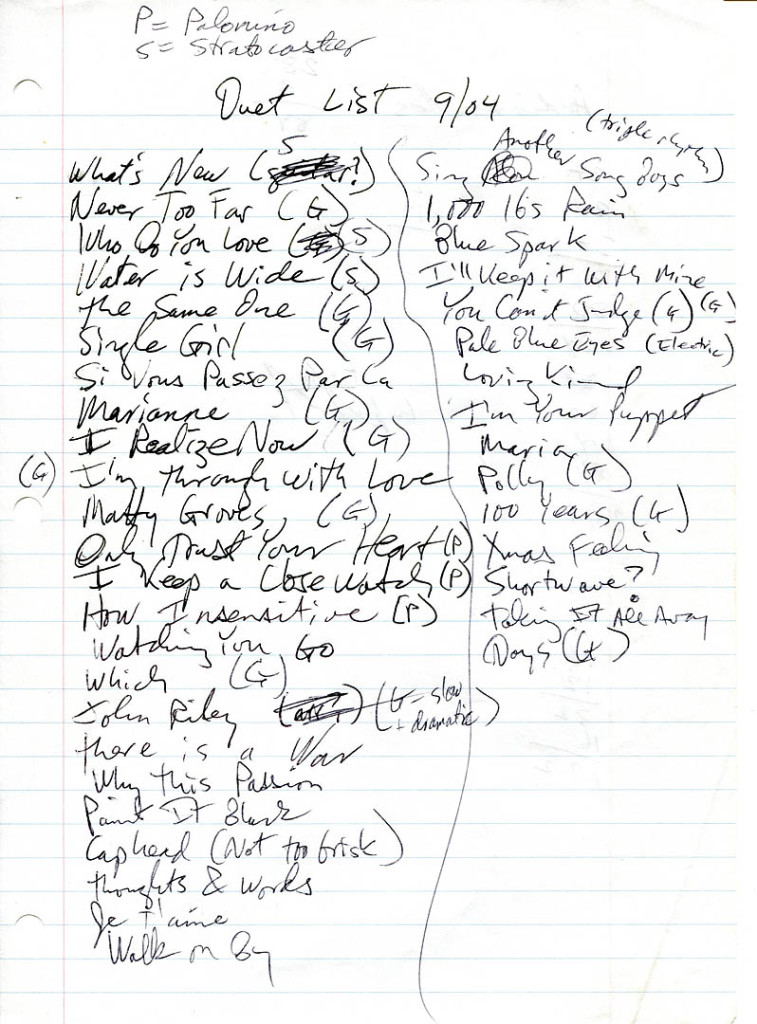

Ken Reynolds, Doug Hubley and Gretchen Schaefer: the Howling Turbines, circa 2002, at a party at the Westbrook home of Rikki and Bob Gallagher. Photo by Jeff Stanton.

My first Accordion-O-Rama purchase was the used, black and silver Lira 120-bass that I got in 1987 and played with the Cowlix and the Boarders. Carefully packing the old Lira accordion according to Peter Shearer’s instructions, I shipped it ahead to the Big City. It was a trade-in toward accordion No. 3: a sweet blue Excelsior 48-bass that weighed about a ton less than the Lira and had a full set of musette reeds, as opposed to the Lira’s half-musette.

This did not represent an accordion renaissance for me (that would come later, with Gretchen’s and my current band, Day for Night). But I did use the Excelsior, aka Bluebell, on a few numbers that would come to symbolize the late Turbines for me — both sung by Ken Reynolds.

Ken with the djembe, at right, as Doug drones on. Jeff Stanton photo.

Lou Reed’s “Pale Blue Eyes” was a revival from our old band, the Mirrors. Inspired by a 1970s affair, Ken had sung it poignantly then, but now in our maturity and with the streetlights flickering on around the Howling Turbines, it gained a new depth of emotion.

Reed’s onetime Velvet Underground colleague John Cale wrote “I’m Not the Loving Kind.” If stunning electricity and pounding tom-toms defined the Turbines’ early years, this song — Ken’s unforced singing, the accordion, the bongoes, Gretchen’s bass and our restrained backing vocals — symbolizes the end game to me. For all its simplicity, it was one of our best numbers. It came so late in the game.

The oddest turn we took was toward Brazil. Sometime in the late 1990s, I bought for Gretchen a compilation of Stan Getz bossa nova recordings, and I would borrow it for my 45-minute commute to work. I got hooked. It was mainly the rhythm: I remember one day in the Jetta on the Maine Turnpike, the road noise drowning out nearly everything but João Gilberto’s guitar. And it was so infectious I couldn’t stand it.

We had already made a pass at jazz, in our technically circumscribed way. (I remember drifting into the back yard in an ecstatic haze one summer day after work, trying to puzzle out the chords to “I’m Through With Love.”)

Bossa nova seemed like the aesthetically appropriate next step. The Turbines didn’t stay together long enough to get deep into it, but we learned enough to give our sets a spice that you just wouldn’t get from any other band from Portland, Maine, that was also playing Buddy Holly, Johnny Cash and John Cale numbers.

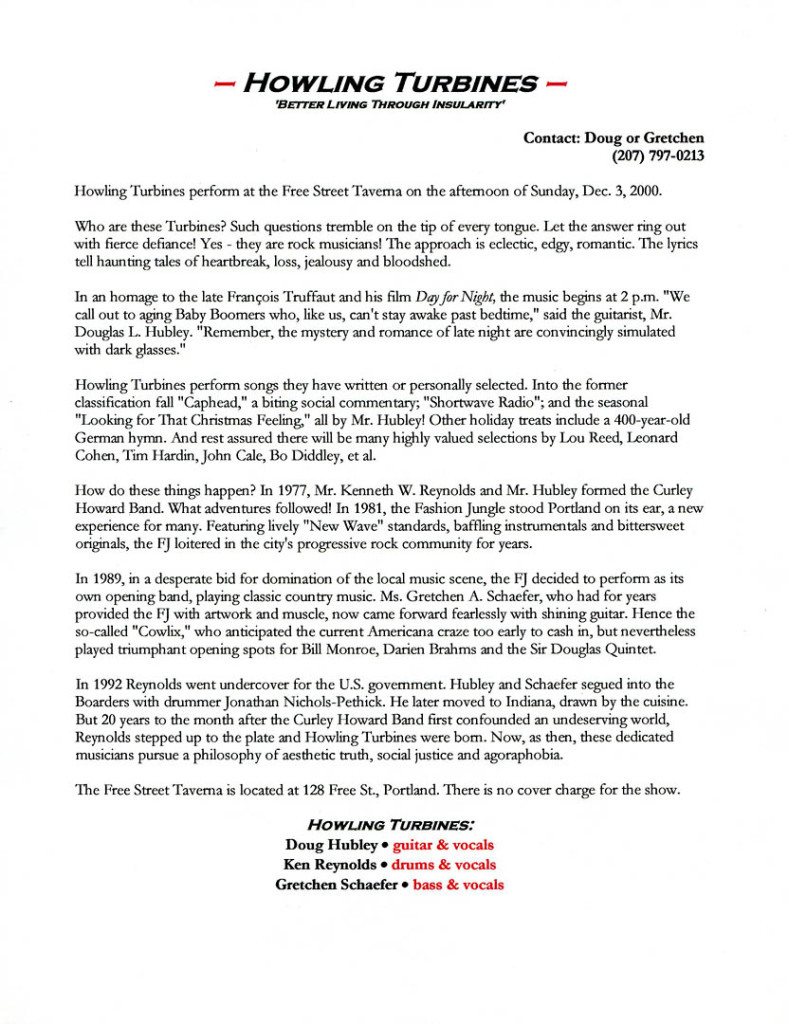

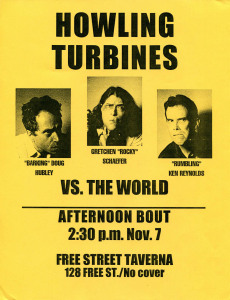

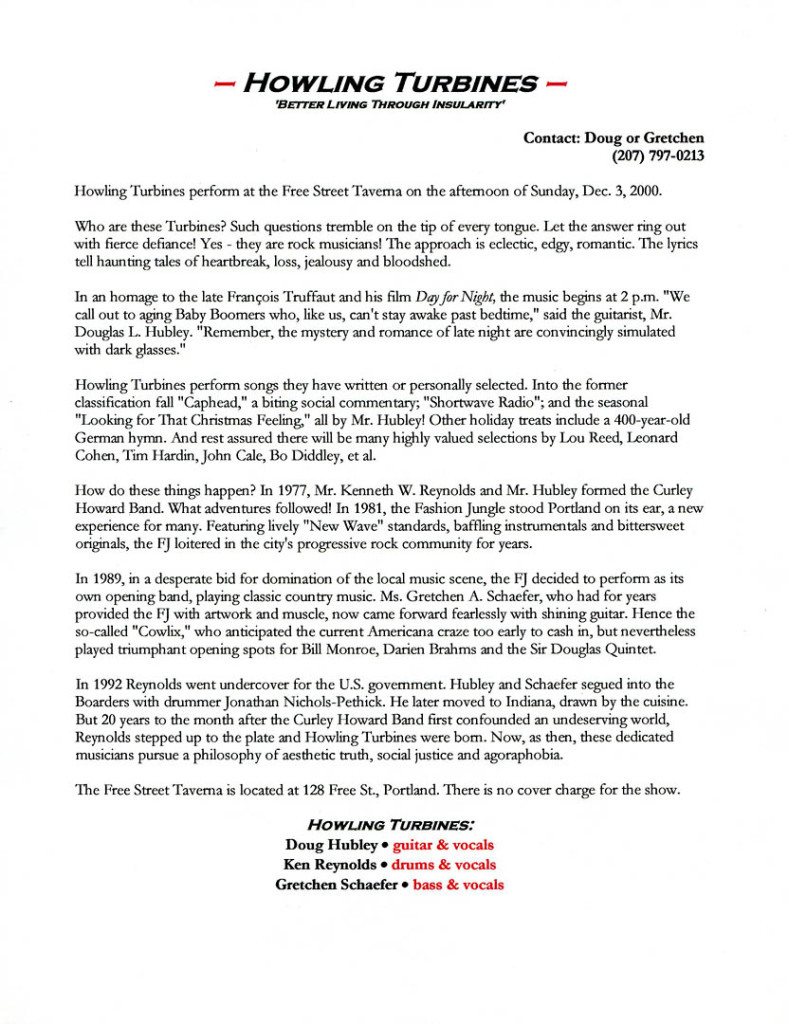

Who are these Turbines? Read and find out, if you would be so bold! Hubley Archives.

From our early days we revived Cale’s “I Keep a Close Watch,” setting it to a fast bossa nova beat. As opposed to Cale’s full piano chords or the stately Rickenbacker 12-string setting we had started out with, this late rendition had a chilly sparsity that rendered the stark lyrics all the starker.

And from the Gilberto-Getz-Gilberto songbook, in an audacious grab that resolved into an ideal Howling Turbines selection, we picked up Benny Carter and Sammy Kahn’s “Only Trust Your Heart.” It was Gretchen’s best vocal performance with the Howling Turbines, and we hung onto it into the early days of Day for Night.

But the crows were gathering around us, if we had just had the perspicacity to wonder what the cawing was about. Descendants of a band premised on the primacy of original material, the Fashion Jungle, the Turbines nevertheless learned no new originals after 1998’s “Caphead” — which, in fact, was the last song I wrote until 2010.

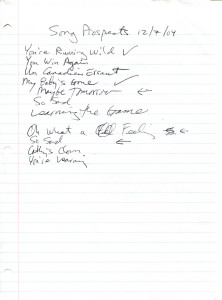

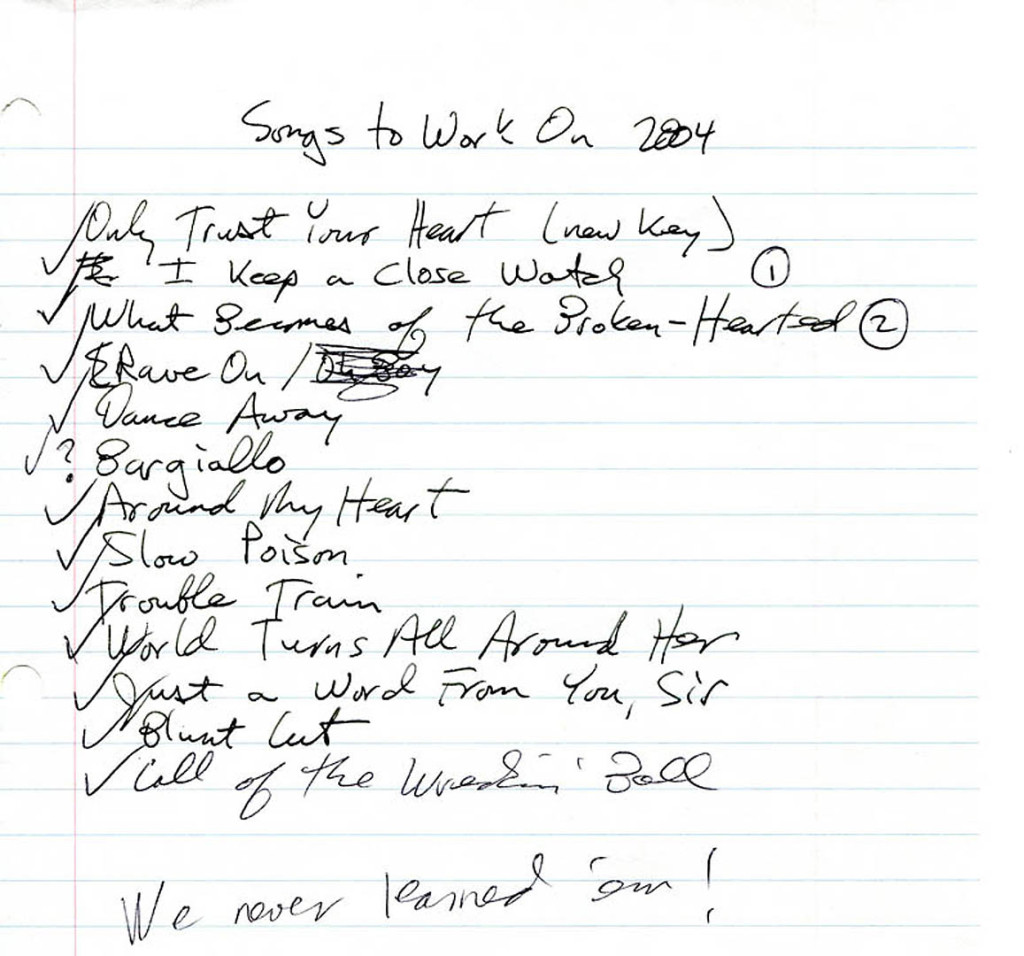

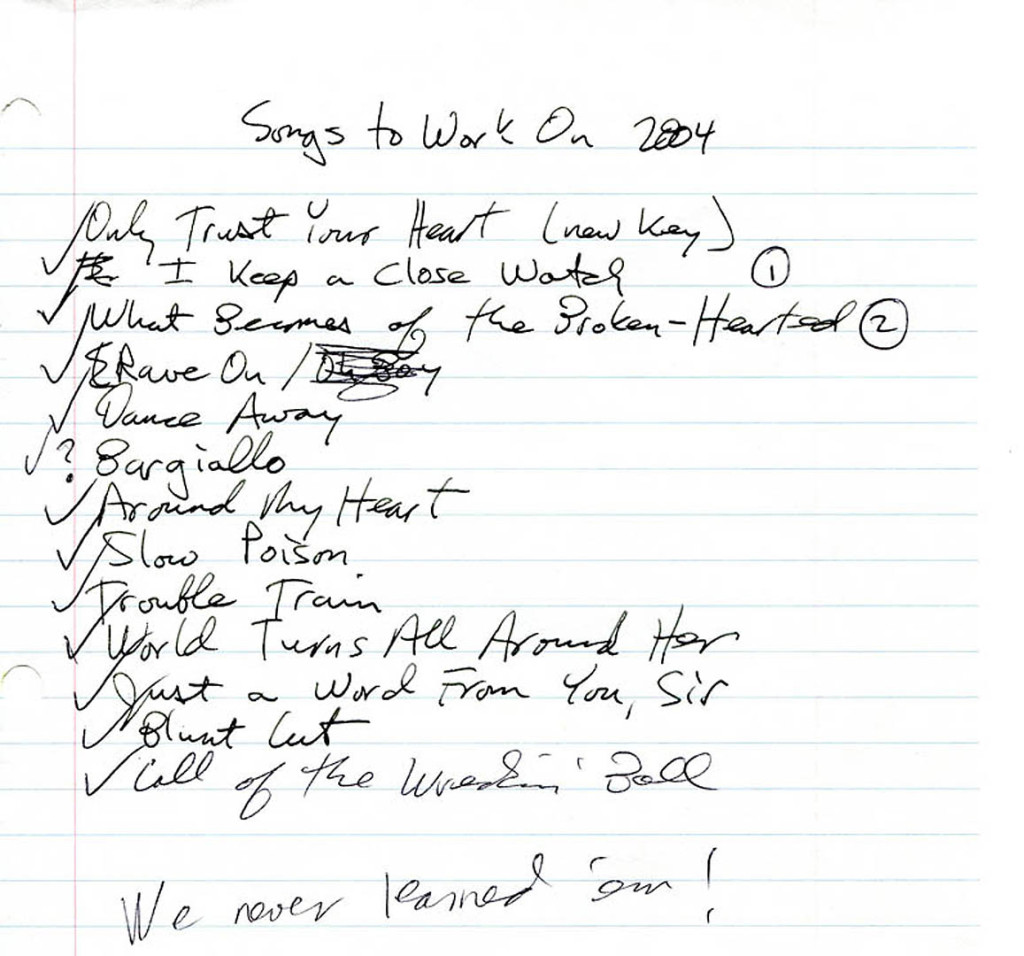

So much to do and so little time. The songs that I prepared for the Turbines to learn or revive in early 2004. Hubley Archives.

We remained loyal to the notion of being an originals band even as the well ran dry, clinging to Big Hits from the Old Days dating back even to the FJ. But 15 or 20 years after the first flush of inspiration, it took some emotional gymnastics to conjure up enthusiasm for “Shortwave Radio” and “Groping for the Perfect Song.”

In the end, what stopped the Turbines’ spin was the same stick in the blades that stalls most bands: Our lives were changing in ways that couldn’t accommodate the band. I think that was particularly true for Ken. He got involved with a woman in the early 2000s and wanted, naturally, to devote time to that relationship — a desire complicated by his job at the post office, which almost invariably entailed evening or overnight shifts.

Paying work, and love: It’s hard not to prioritize those.

In January 2004, in what I considered the lead-up to a fresh start, I prepared several cover songs for us to learn or revive (including “Bargiallo” by the Italian band Madreblu, Jimmy Ruffin’s “What Becomes of the Broken-Hearted” and the bossa nova version of “I Keep a Close Watch”).

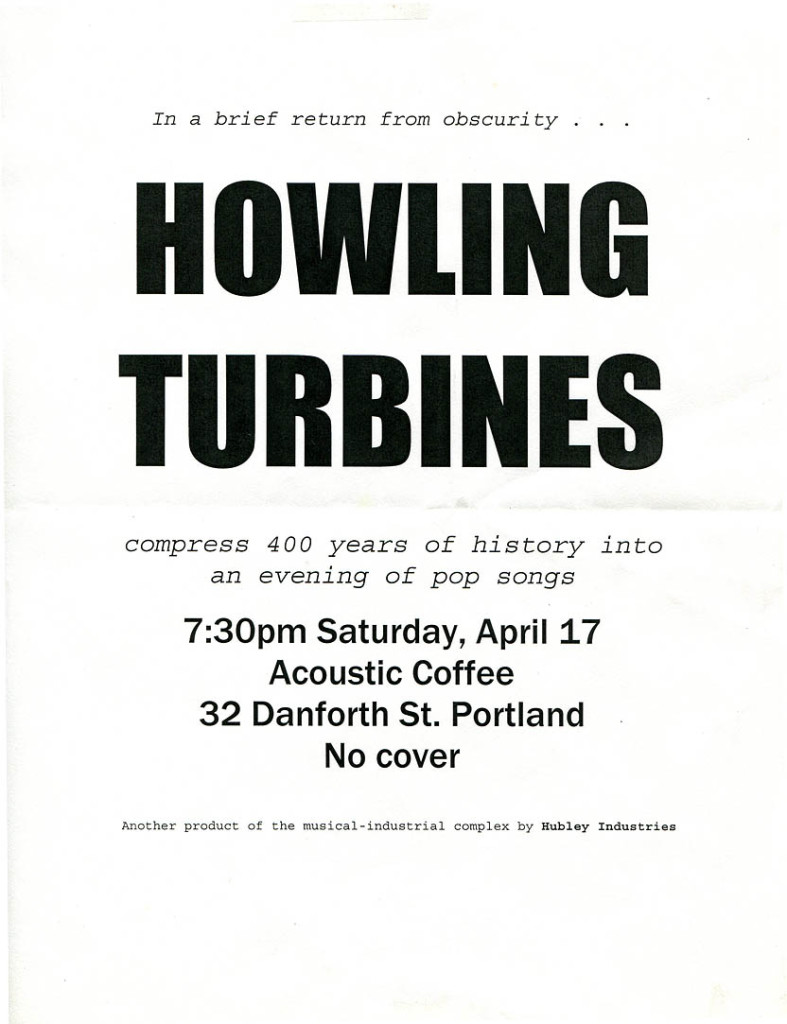

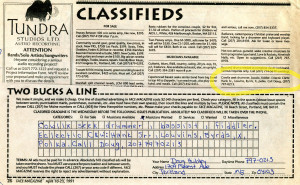

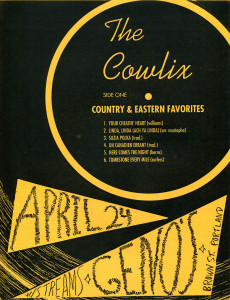

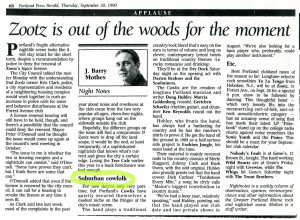

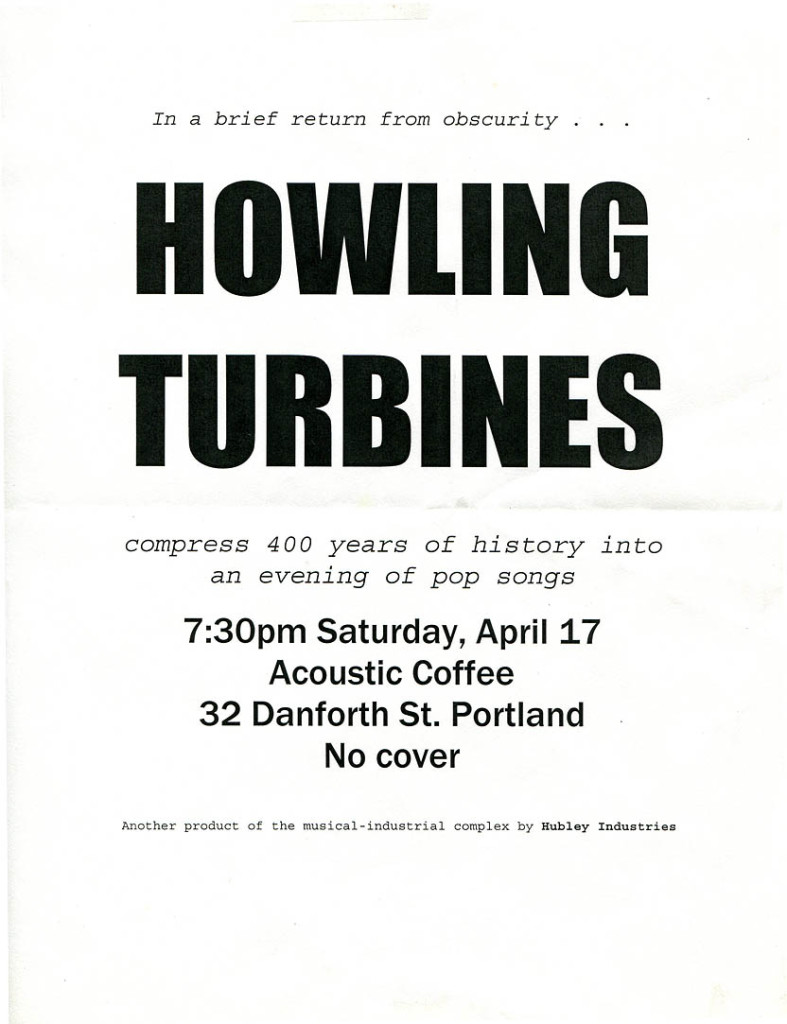

“Brief return from obscurity” refers to the fact that the Turbines played only private parties after the sale of the Free Street Taverna, our sole public venue. And the Acoustic Coffee date turned out to be the Turbines’ last gig. Hubley Archives.

Three months later, on April 17, the Howling Turbines played what turned out to be our last gig, at a place on Danforth Street called Acoustic Coffee.

We played pretty well — and not acoustically, despite the club name — but it was an uneasy date, even though Gretchen and I, at least, had no idea it was the band’s finale. The club owner had booked us but didn’t really seem to like us, and had weirdly passive-aggressive ways of showing it.

Among our friends in attendance were Barbie Weed and Tracey Mousseau. The Acoustic Coffee chairs were folding chairs, and Barbie’s collapsed, trapping her thumb in a shear point and injuring it. Tracey took her to the emergency room. As I recall, the club owner wasn’t nice to Barbie about the injury his defective furniture inflicted on her. Sorry our friend hurt your chair, mister!

We hauled the gear back to the basement and said our goodnights as usual and, surprise, the Howling Turbines were done . . . as we realized sometime later. There was no big breakup scene or even a discussion — and we’re still friends with Ken — but he never came back for another rehearsal, returning to the basement only several months later to retrieve his drums.

For Gretchen and me, what followed was three years in a musical wilderness — much of it Brazilian.

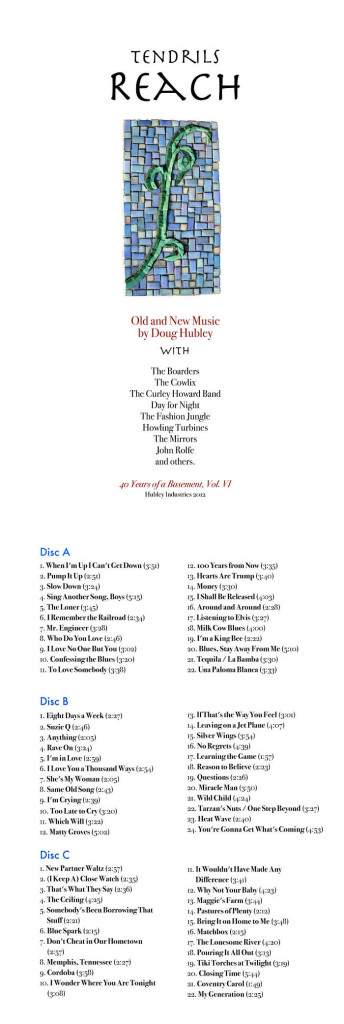

I present these rehearsal recordings an as accompaniment to this post, but it’s really a mismatch. The post dwells on the last years of the Howling Turbines, in which our music had a distinct decline-of-the-empire quality. These songs, though, are from our growth years, 1998-99. I offer them because I can’t put cover versions up for sale. But it was covers, by Lou Reed, John Cale, Leonard Cohen and others, that really formed the soundtrack of this chapter of the band. The excerpts embedded in the text above will give you a better sense of what was happening musically.

Visit the Bandcamp store.

- Looks Like My Monkey Got Loose (Hubley) I was sitting on a bus in January 1996, waiting to leave Elm Street, when I thought of a crazy monkey as a metaphor for lack of self-control. (You may not believe it, but I myself have had impulse-control issues.) The song started out with the Boarders and endured into the Howling Turbines, who recorded this take in a 1998 rehearsal. Gretchen and I gave up the Little Debbie Swiss Rolls once and for all after the news about transfats came out, but the jones never goes away. Copyright 2010 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.

- Just a Word From You, Sir (Hubley) The second of two very different versions of this number. One of two songs I wrote for the Turbines, this number is generally about my relationship with authority, and specifically about Stalin, Leonard Cohen and God. The original arrangement was slow, grinding, heavy and metallic. I now prefer the original to this sprightly tap-dance setting, but the later one too has its charms and is certainly more dynamic than the other. This 1999 rehearsal recording is a recent discovery in the Basement vault. Copyright 2010 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.

- Watching You Go (Hubley) Another holdover from the Boarders. I regard this as one of the best songs I’ve written. Fate is generous with opportunities to dwell on the loss of loved ones, but it took the death of my cat Harry to get me to actually write about it. Fortunately I was able to expand the lyrics beyond “my kitty died.” A 1999 Howling Turbines rehearsal recording. Copyright 1996 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.

- Why This Passion (Hubley) A wordy attempt to trace the course of a lovers’ quarrel, this high-romantic epic started out with the Chapman-Torraca Fashion Jungle in an over-elaborate arrangement, became more straightforward in the FJ’s later incarnations, and finally, with the Boarders, picked up the “camel beat” heard here. Given Ken Reynolds’ latter-day attraction to the tom-toms, that beat was a natch for him, as you can hear in this 1998 or 1999 rehearsal recording. Copyright 2010 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.

Notes From a Basement text copyright © 2012–2015 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.