Day for Night: O Brothers, Where Are We?

Visit the Day for Night gift shop at Bandcamp!

Day for Night’s first gig took place in July 2007

Gretchen Schaefer poses for a picture during Day for Night’s public debut, at the Lewiston (Maine) Farmers Market in July 2007. Hubley Archives.

at a farmers market in downtown Lewiston, Maine. The market coordinator was a student at the college where I work, and I responded to her open call for musicians.

As we recall, it went pretty well. Market organizers allotted us a sunny patch of grass along the sidewalk, and we were OK with the lack of stage and amplification. Punctuating our music with changes from guitar to accordion (me) and to autoharp (Gretchen), we jittered along steadily through our two sets till late afternoon.

There were a few compliments, some kids found us briefly intriguing, most people gave us exactly the kind of non-attention we were hoping for as we rediscovered our performing reflexes.

Day for Night performs the Everly Brothers’ “Price of Love” at Bates College, Nov. 30, 2007. Photo by H. Lincoln Benedict.

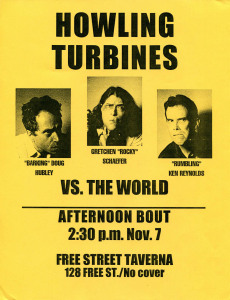

For Gretchen and me, the three-year interval between our last date as the electric Howling Turbines, with drummer Ken Reynolds, and our first as the acoustic Day for Night entailed adventures as diverse and gnarly as

- learning to blend our voices and instruments without the cover of drums;

- realizing how productive we could be in a cabin in Colorado;

- finding that, darn it, we just weren’t cut out to be bossa nova musicians after all;

- and, as a corollary to that last, figuring out just what music we should be playing.

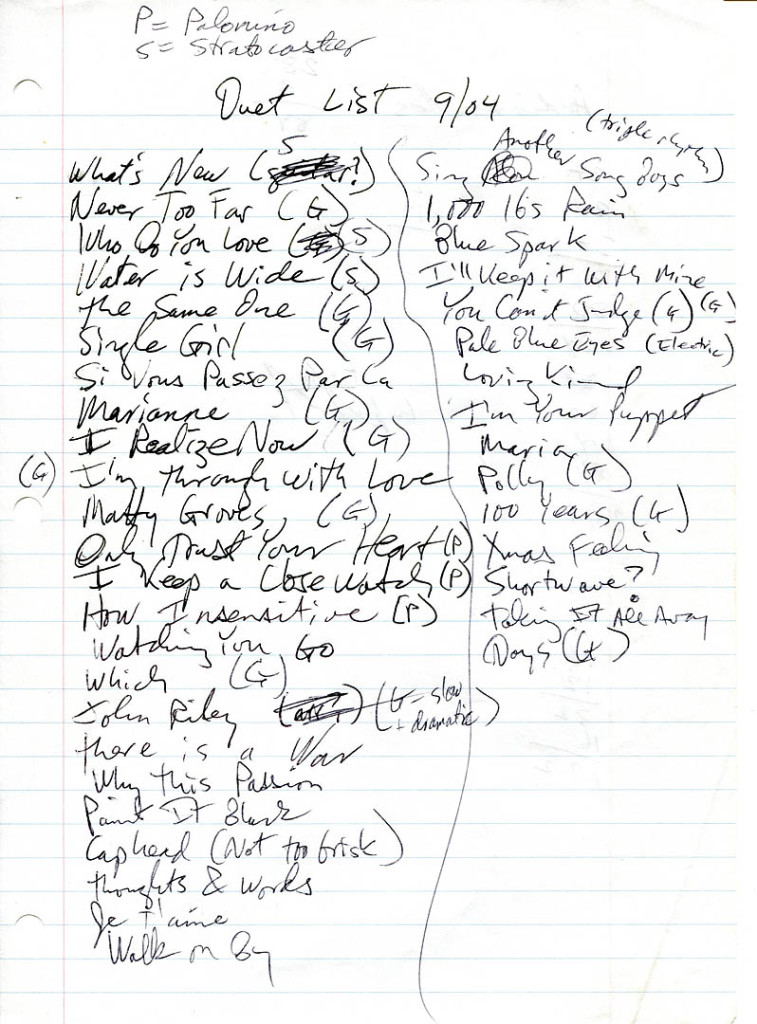

Answering that last question was easy and hard. Easy because even in the depths of bossa nova madness in 2004–05, we knew that country music would always be Day for Night’s prime directive. Having drifted away from bossa nova, though, we next had to get serious about country, which meant figuring out just what country meant for Day for Night. That was the hard part.

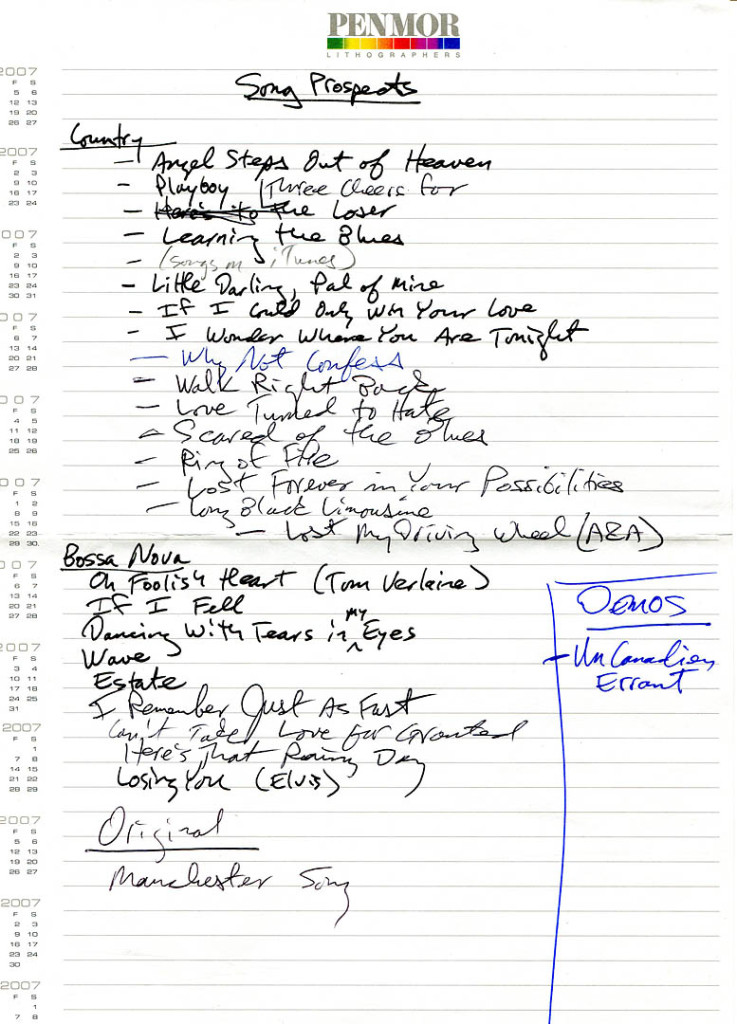

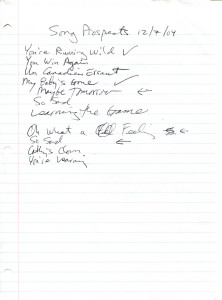

This prospect list from late 2007 shows the musical schizophrenia that I was inflicting on Day for Night. Note that the bossa nova prospects (none of which we ever tried) included sources like Graham Parker, Tom Verlaine and Elvis Costello. “Manchester Song,” by the way, finally took shape two years later as “Bittersweet.” Hubley Archives.

But she did grow up hearing her father and a mandolin-playing friend do Hank Williams and other country songs, mixed in with 1950s–60s pop, in parties on the boat in Long Island Sound. (Gretchen’s main guitar for many years had belonged to her father.)

Her own early playing, as a teenager with friends on acoustic guitars, explored the borderlands between country, pop and folk without worrying too much about categories.

For Gretchen, the Child Ballads — Francis Child’s compilations of British folk ballads, those blow-by-blow narratives of intense love and death — were a powerful revelation in the 1970s. Today, the kind of country that she finds most compelling follows the path from those centuries-old ballads through the Appalachians to seminal players like Ralph and Carter Stanley.

As for me, my lack of stylistic boundaries is a frequent refrain in these posts. As a teenager, I was more concerned with means than genre: More than anything, I wanted to play electric music.

Which affords a handy segue to a musician who had an important influence on my genre promiscuity — that is, he provided a broadly accepted rationale for it. Yes, in my perceived Lonely Guy™ solitude back there in the early 1970s, I was one among the millions around the world captivated by former Byrd, former Flying Burrito Brother Gram Parsons.

Gretchen Schaefer and Doug Hubley in a Day for Night publicity photo taken in 2008 by the Kodak self-timer. Hubley Archives.

His singing was touching — especially with Emmylou Harris, as we’ll never let her forget, as if she could; his tragic story was highly romantic as long as you didn’t have to deal with the lawyers afterward; and his view of music was one that I immediately adopted as my own.

“I just say this — it’s music,” Parsons is supposed to have said (I can’t find an attribution). “Either it’s good or it’s bad; either you like it or you don’t.”

Such thinking struck naive me like a bolt from the blue — even after growing up with groups like the Beatles and the Rolling Stones that were essentially exemplifying the same thing, only without the pedal steel or Nudie suits.

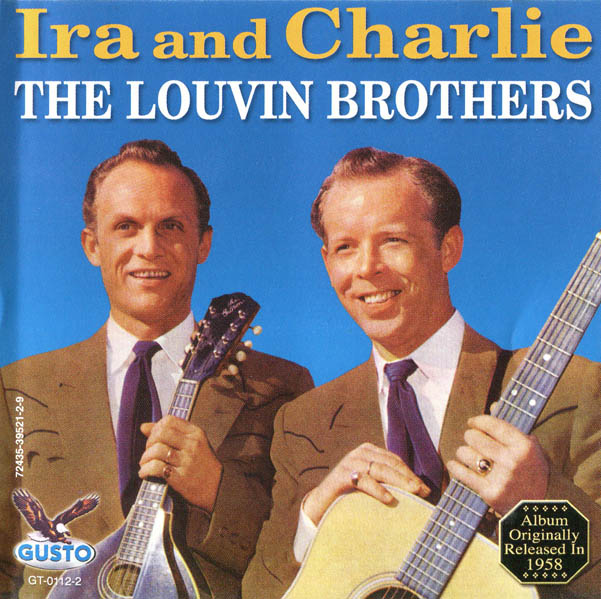

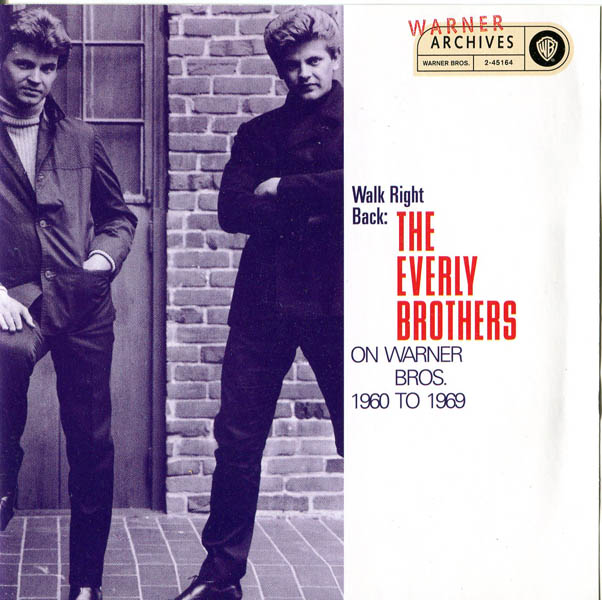

All that being said, Day for Night’s way-finding was a slow but agreeable process. In the beginning we had outstanding, if unsurprising, guides. We knew we wanted to emphasize harmony singing, and for that there were no better inspirations than the Everly Brothers and the Louvin Brothers.

Coming from country music, the Everlys played rock-pop that often worked well as country (as opposed to some of their deliberate country efforts that didn’t really cut the mustard in either camp). In the short run, that was good for Day for Night. We could brandish our country identity but still, flashing our Cosmic American Music badges, keep trying to work the pop, rock and R&B in there too.

The Louvins were tougher. As brilliant as their singing was and as strong as their material could be, they recorded enough dogs to fill a kennel. “Red Hen Hop”? “The Stagger”? I’m asking you!

The Louvins were tougher. As brilliant as their singing was and as strong as their material could be, they recorded enough dogs to fill a kennel. “Red Hen Hop”? “The Stagger”? I’m asking you!

We’d pick up one or two songs from each Louvin Brothers album, having sifted through the rest with gritted teeth (a mixed metaphor that actually works pretty well in this instance).

For Gretchen and me, it was a Louvin Brothers day after an evening of Maine classical music history. The night before, we’d heard a concert by 91-year-old classical pianist Frank Glazer, marking the 70th anniversary of his New York City debut by reprising the same ambitious program he’d played at Town Hall all those years ago.

Gretchen Schaefer, smiling and strumming during one of Day for Night’s first performances. The Bobcat Den, Bates College, Nov. 30, 2007. Photo by H. Lincoln Benedict.

The concert was inspiring. I felt some sublimal connection between Glazer’s dedication and my own persistence (which isn’t quite the same thing). The dash to the car through the deluge wasn’t inspiring, nor was our night in the dowdy motel next to the turnpike on-ramp. We were glad to head home. We listened to Ira and Charlie: The Louvin Brothers, from 1958.

And Ira and Charlie was a revelation. It was the Holy Grail and the key to the city. We liked everything we heard: Chet Atkins’ Gretschy sophistication mixed with Ira’s out-of-the-blue mandolin fills; Ira’s soaring harmonies against Charlie’s plainspoken soulfulness.

Driving back to Portland, we listened to the CD once and then played the whole thing again — and I never do that. Over the next year or so, Day for Night learned half the tracks on Ira and Charlie — and we still do five of them. (“I Wonder Where You Are Tonight,” “Have I Stayed Away Too Long” and”Making Believe,” in addition to “Too Late” and “Here Today.”)

Ira and Charlie turned out, over time and in a subtle way, to be a pivotal point in Day for Night’s slog toward refining its musical identify — a slog that, after all, took four more years and the addition of a mandolin to really complete. (All of which you can expect to read about, in excruciating detail, in the coming months.)

And what made that record so influential was not at all exalted or profound. It was simply the intersection of quality and quantity: After months of shopping around for material, the Ira and Charlie windfall gave us a direction and a goal.

Doug during the Everly Brothers’ “Cathy’s Clown” — the “Magic Fingers” capo gives it away — at Day for Night’s Nov. 30, 2007, show at Bates College’s Bobcat Den. Photo by H. Lincoln Benedict.

Mental space like the mountain landscapes in Colorado, with the open air, the transfixing beauty and the long views that feel like freedom.

Notes From a Basement text copyright © 2012-2015 by Douglas L. Hubley.

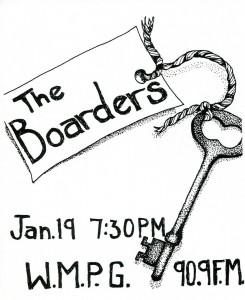

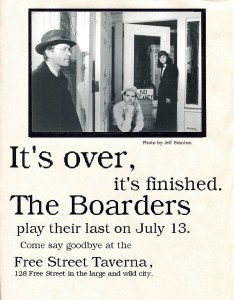

![Late in the 1860s novel Little Women, heroine Jo March, dreading her friend Laurie’s budding romantic feelings for her, tells her mother she feels “restless and anxious to be seeing, doing and learning more than I am.” Her solution is to move to the city, to live and work in a boardinghouse. There, she has a room to herself, time to write, and the welcome distraction of friendships with her fellow boarders. — Ruth Graham, The Boston Sunday Globe, Jan. 12, 2013 [Week of March 24] Boarders Let's begin with something deceptively obvious. Larger musical groups are empowered by their capacity for complexity. Smaller bands are empowered by the need to keep it simple. Obvious, for sure, but for the musicians involved, it's a powerful reality that encompasses infinite subtleties in both directions -- perhaps unexpectedly so in the case of the minimal. The richness of potential there can be highly gratifying. Every time I have gone from a larger to a smaller band, I've felt suddenly light, ready to fly. This was especially true in the case of the Boarders, the trio remaining after two musicians departed our so-called country band, the Cowlix. Singer Marcia Goldenberg left in March 1994 and violinist Melinda McCardell in May, after one last gig. My fellow remnants were Gretchen Schaefer, who played bass and guitar, and drummer Jonathan Nichols-Pethick. I played guitar and accordion, proposed much of the material and sang most of it. Post-Cowlix, we wasted little time finding a direction. And circularly enough, our direction was to be the Boarders. Atop a hard core of held-over Cowlix country and folk-dance repertoire, we added pop-rock by Buddy Holly, Jackson Browne and others. I was gratified to bring in two songs by Tim Hardin, one of my first big influences, to the repertoire. We learned two by the Kinks; the Oysterband's brilliant "When I'm Up"; Anne Savoy's adaptation of the Cajun song "Mon Chere Bebe Creole." From the torch song catalog came "What's New" and "I'll Be Seeing You." We glommed up enough Leonard Cohen to jokingly bill ourselves as Portland's only L.C. tribute band, even tackling the French Resistance anthem "The Partisan," which Lennie covered on his second album. And we revived several originals by my pre-Cowlix combo, the loudly romantic Fashion Jungle. Speaking of which, among other improvements that came with the Boarders, it was here that I felt at home as a songwriter again after five years adrift. It was ironic, or at least telling, that toward the end of the 'Lix I was thinking about revisiting Fashion Jungle material (and we even picked up "Shortwave Radio"). Apparently I am on a short chain fastened to a post in the ground, because I walk in one direction until the chain is wrapped completely around and then I wind it again the other way. In the four years of the Cowlix, I wrote two songs: "Slow Poison" and "Trouble Train." In the two years of the Boarders, I wrote three, including two that I consider among my best, "1,000 Pounds of Rain" and "Watching You Go." And for the first time since the Fashion Jungle, I wasn't the only songwriter in the band. We hung onto Jonathan's "All Over," and he and his wife, Nancy Nichols-Pethick later presented "Tragedy." Nostalgia wears rose-colored contact lenses, but it seems to me that our musical interests were as harmonious as everything else about the Boarders. I don't recall Gretchen, Jonathan and me ever discussing our repertoire in broad or aspirational terms, and neither did we disagree about material. We just brought songs in and, for the most part, played them. It was a relief to lose the country music fiction espoused by the Cowlix, a band with a long stylistic reach and a grasp that almost matched. As previously noted, I, at least, had started violating the "country" descriptor early on. And now here were the Boarders with no such mandate to obey or defy. Like the Cowlix, we had the range to pull off a variety of music, but there was a crucial difference: What the 'Lix lacked and the Boarders possessed was a collective personality focused enough to forge an identifiable sound from some disparate types of music. Much of that personality was purely musical and organic, but -- and I know it will shock and surprise you that such things happen in the music biz -- some slight contrivance went into the Boarders' public identity. The three of us had zero interest in retaining the Cowlix name. Not only did we wish to leave the past in the past (as I am obviously so dedicated to doing), but we had discovered along the way that we weren't the only ones using that name. Pretty obvious moniker for a country band, after all. I don't recall where or how "Boarders" turned up, but it seemed sufficiently random-yet-meaningful, that irresistible combination, to work for this "new" band that seemed capable of anything. The richness of the Boarders' prospects and potential, coupled with my decade-plus experience, as a music journalist, with musicians angling for my attention, prompted a fairly focused publicity campaign. We even created press kits, including a band history (remarkably free of factual content), demo tapes, a sample lyric ("Trouble Train"), publicity photos by longtime friend Jeff Stanton -- and a key pin. Key pin? Just like it sounded: an old-fashioned lever-lock key with a pin-back epoxied onto it, so it could be worn as a pin. The key concept was derived from the boardinghouse concept, and the whole works was derived from my realization that journalists and club owners would be more likely to remember a band that gave them presents. Who doesn't like presents? I have no idea whether the key pins made any difference to our getting work -- although we did get work. But, revisiting the two key pins that I still have from that exciting Boarders efflorescence 20 years ago, I would like to think there are still a few Boarders key pins turning up, from time to time, on the sport jacket lapels and cloche hats of Portland's hip-and-cool.](https://www.dhubley.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Boarders-JS-LEDE-1024x680.jpg)