Notebooks From A Basement

Before the server collapses under the demand, join the mad rush to experience music by Doug Hubley at Bandcamp!

As a writer, I have an idealistic view

of notebooks as symbols of hope and potential, as a means to the next great piece of work.

Idealism figures in there somewhere, anyway. (I do all right, but the next great piece of work?) More dominant, perhaps, is my tendency to mistake acquiring objects for doing, heaven forbid, actual work: On some level I feel more likely to access hope and potential through an impulse purchase at the drugstore, perhaps while picking up my sinus prescription, than through rummaging around in my inner resources.

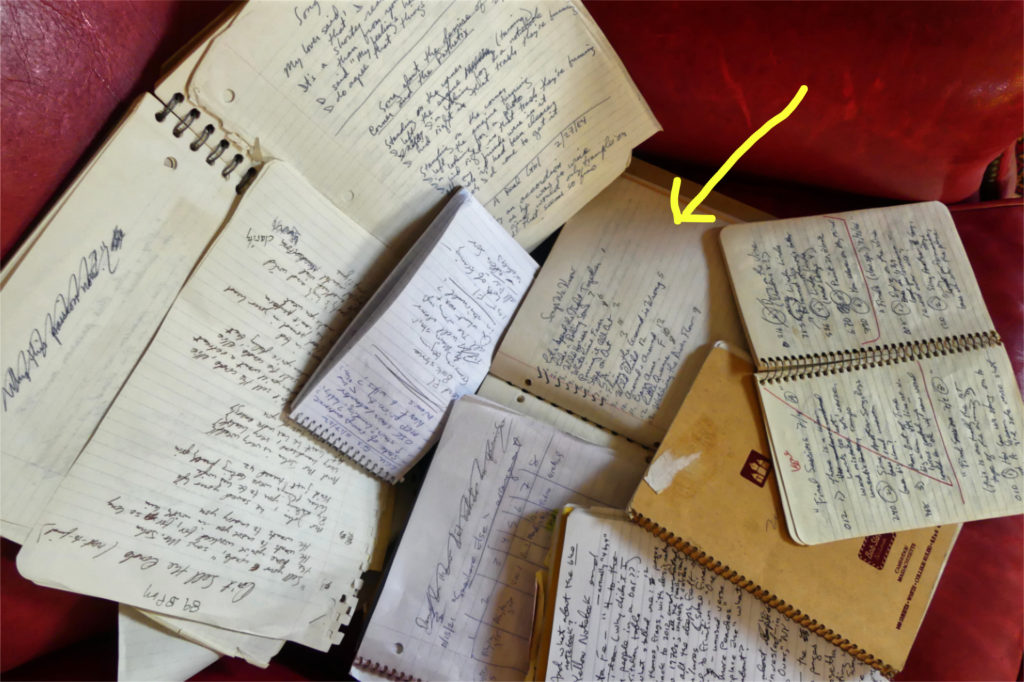

A loose-leaf notebook obtained in seventh grade lives on in the Basement. Its stiff cloth cover, the color of pea soup, is dense with doodling and the front panel is held on with packing tape. This ancient tome now holds the first volume of my catalog of audio recordings, listing about 110 reels of tape, a few of which are nearly 60 years old (e.g., Steve Sesto and I doing “Yellow Submarine”).

Another notebook, which contains the second volume of recordings (now including digital!) is in much better shape. The binder itself is only 35 years old.

Those notebooks live in the Basement with countless others. They date from every decade and represent every notebook format. They contain aspirational song lyrics, never-realized TV script ideas, notes from college classes, names of party invitees, journal entries.

If they can be categorized at all, most of the loose-leaf books are for organizing things that I want to keep, like the tape catalog, and the spiral-bound books are for more ephemeral uses. I keep those, too.

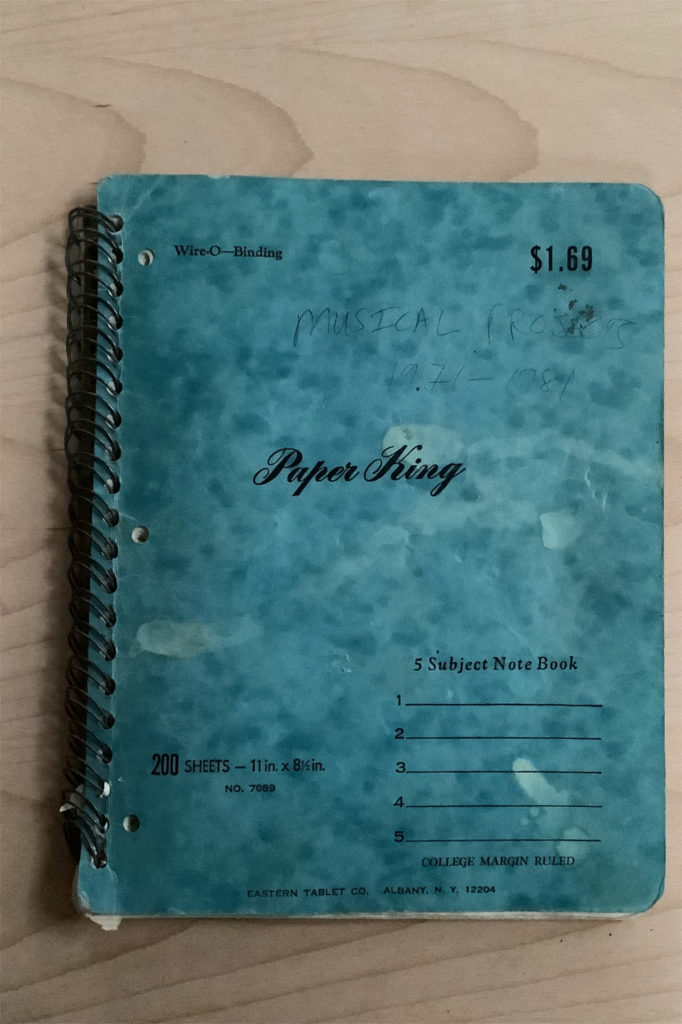

(One especially evocative example is a 200-page Paper King complete with proprietary Wire-O—Binding. Containing set and repertoire lists, a draft treatment for a short story that never got written, and lyrics — a few by me, many by artists my bands were covering — it spans 1971–1981. Most of the handwriting is mine, but it’s fun to try to identify the other scribblers.)

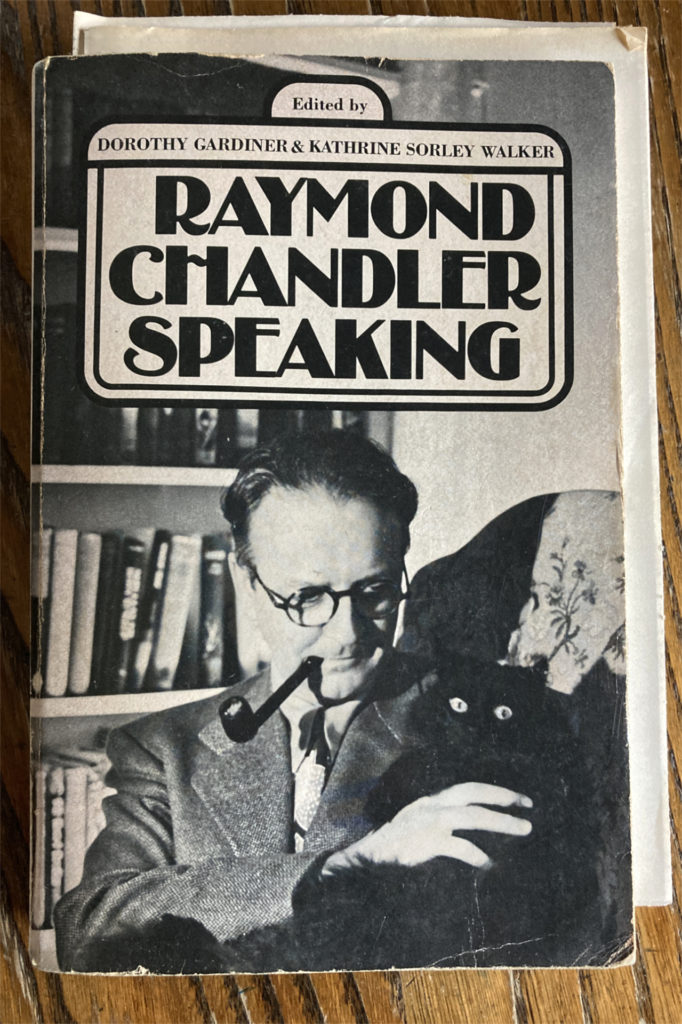

Raymond Chandler affected my attitude toward notebooks. The great detective novelist’s work influenced me deeply during the 1970s: the poignancy of his language, his vision of California as a hollow paradise, his conception of private eye Philip Marlowe as a “lone knight” true to his code but not to much else. (I also appreciated his storylines, which were often as baffling as they were riveting. This quality validated my own inability to plot a story.)

At some point I read Raymond Chandler Speaking, a collection of excerpts from his letters and other incidental writings. As articulated in Speaking, Chandler’s thoughts about his own work taught me a lot — although they no longer read like gospel since I have come to better understand frailties like insecurity, defensiveness, self-deception and reflexive isolation.

Anyhoo, one takeaway from the book was that a writer should keep a working notebook as a place to store, develop and re-examine ideas, as well as to capture stray facts and thoughts that could prove nourishing to a writing project.

I fell in love with that idea — despite the fact that later, as a professional writer, I rarely put it into practice. Instead, I employed notebooks almost exclusively for, guess what, taking notes during interviews and events that I was covering. (In those cases, of course, I had to use proper reporter’s notebooks, hoping that the image would bolster the reality.)

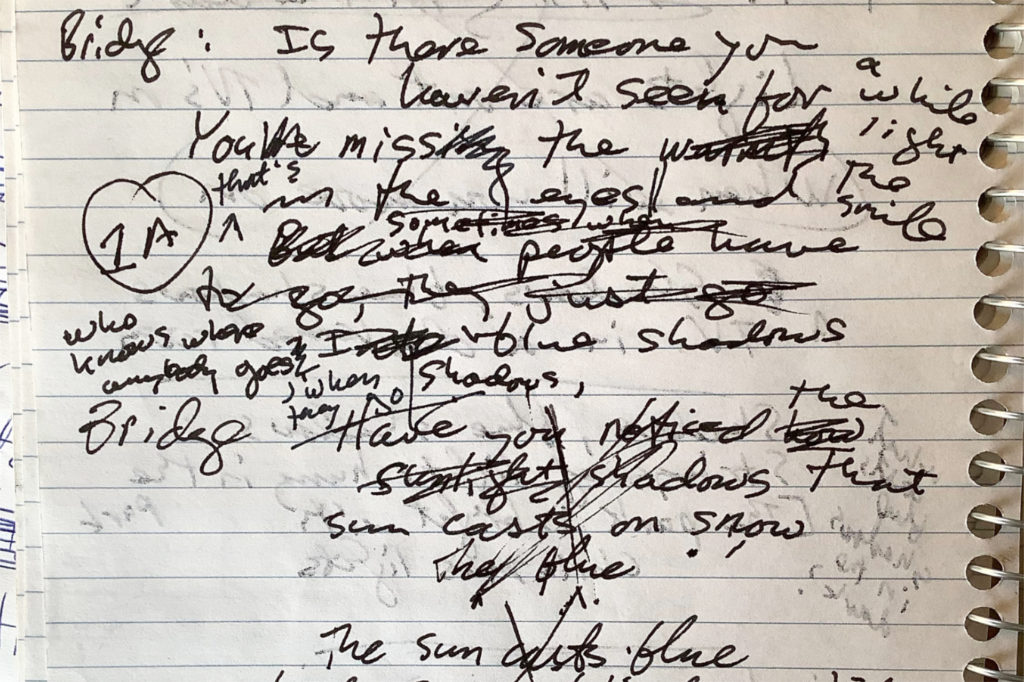

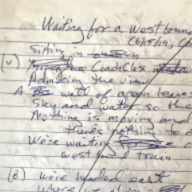

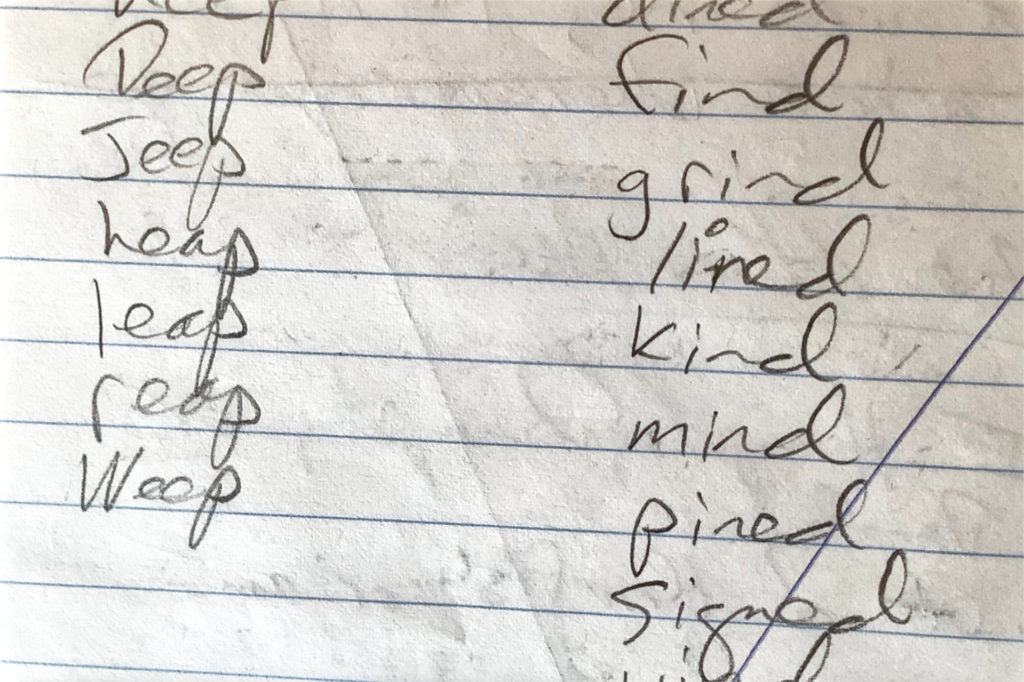

When I finally did start using notebooks for the kind of forward-looking, speculative idea storage that Chandler prescribed, it was for a whole other writing genre: song lyrics. To be clear, I’ve always used cheap notebooks for songwriting, albeit in a very narrow way: I scribble lots of words that can later be distilled into something I might want to sing. That’s the hope, at least.

An idea drives the scribbling, and sometimes the scribbling even engenders more ideas. A nice notebook from the drugstore provides a handy pre-organized supply of paper for all that ink. (I tried pencil, but it smudges.)

This kind of solo brainstorming is the only way I can produce a song. (I’ve always envied the detective novelist Rex Stout, who committed his Nero Wolfe stories to paper only after figuring out a detailed storyline in his head. In what could be a pretty good pun, he created his plots while working in the garden.)

I started writing songs in the 1960s and was producing pretty good ones by the mid-1970s. But they’ve never come along quickly. And as I’ve written in this space before, there was a period of more than a decade when I finished no songs. That became worrisome. So when I returned to songwriting, or it returned to me, I sought to encourage it any way I could. Hence the Raymond Chandler Method™ of notebook keeping.

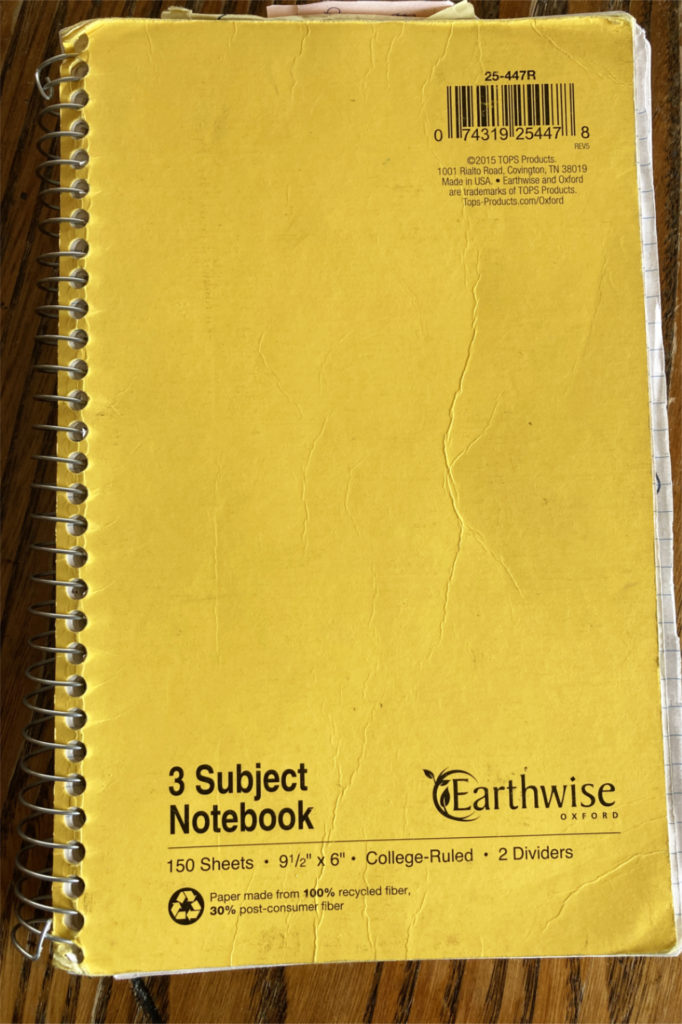

Around 2016 I bought a yellow Earthwise 25-447R, whose 150 pages are divided into three sections. It was manufactured in the U.S. of fully recycled materials and distributed by TOPS’ Oxford brand — those familiar makers of the “iconic index cards, composition books, and study tools that propel so many from classroom to career,” as the marketing folks say (completely ignoring the dilettantes who also pay money for their products). It cost $5.79 plus Maine sales tax. That model is still in production, but now costs twice or even three times as much.

My plan was that the yellow notebook would offer more than a place to scribble, supplementing the requisite blank pages with resources that would foster lyric writing when the scribbling seemed futile. After all, inspiration only gets a person so far.

So into the yellow notebook, for instance, went lyric fragments and song ideas dating back to the 1970s. You could argue that if an idea hasn’t blossomed into a song after 50 years, perhaps it is just dead weight in my Earthwise notebook. But old ideas have sprouted more than once.

For instance, while I was perusing ideas in the yellow book while sitting in a screened porch one damp June afternoon in 2019, one tidbit of moldering old doggerel suddenly glowed red, becoming the spark for a socio-political commentary:

You’re the living end / You’re your own best friend

You’re the learning curve that comes / With going ’round the bend

Eons ago, when those lines first floated to the surface, I knew they were about someone obnoxious, but didn’t know who. That became clear after a certain reality-show host had been in the White House for a couple years, and the resulting song is a paean to arrogant narcissism titled “Mr. Special.”

I referred above to the scribbling phase of lyric writing, the graphomanic activity in which I try to force an idea into bloom. Well, along with the lyric ideas and fragments, the scribbles too loiter on in the notebook, even when they have seemed to stall. I completed three songs in late 2021 and early 2022 — an absolute frenzy of productivity for me — and scribbles written off years earlier as dead ends led to two of them, including “Someplace Else.”

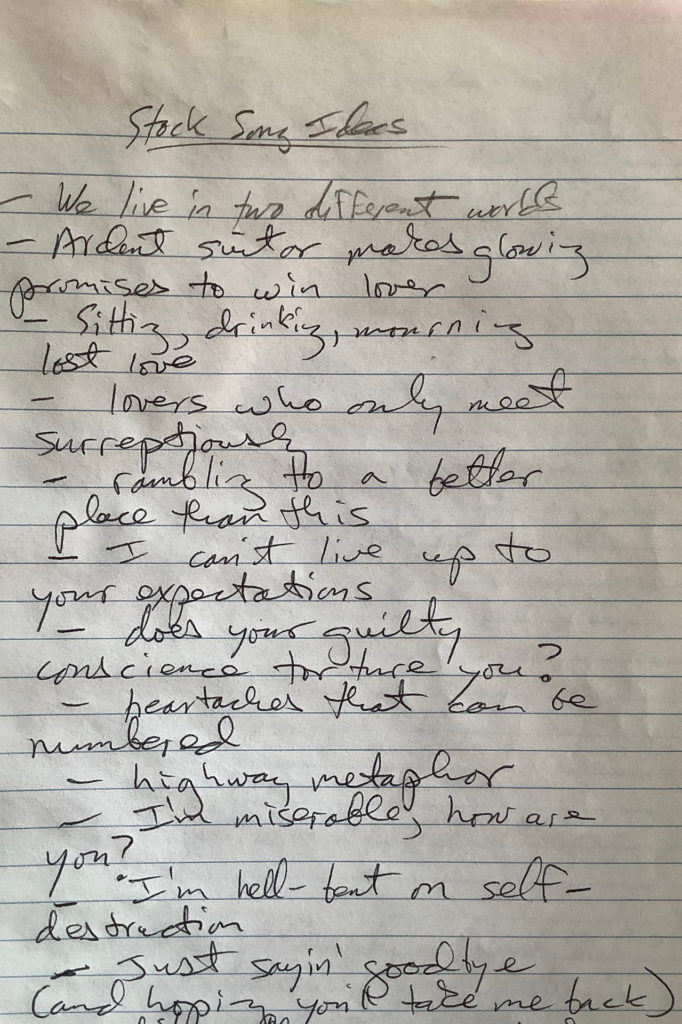

Another notebook resource is a list of common song themes for those times (meaning most of the time) when my own ideas fail to ignite. Is this a bottom-feeder’s approach to finding inspiration? Maybe so. But consider how many perfectly respectable songs share a theme (and sometimes even some lyrics or a title) with other perfectly respectable songs that came before.

It’s a phenomenon especially common in Americana, the musical genre in which Gretchen Schaefer and I perform as the band Day for Night, but it happens all over. As soon as one songwriter is wearing out his shoes walking the floor in despair, everybody else is doing it too and the Zappos of the world are in clover.

That being said, the stock ideas list hasn’t yet provided me with anything usable, but it has afforded many hours of harmless fun coming up with summaries of song plots. How about “sitting, drinking, mourning lost love,” “rambling to a better place than this” or the timeless “I’m miserable, how are you?”?

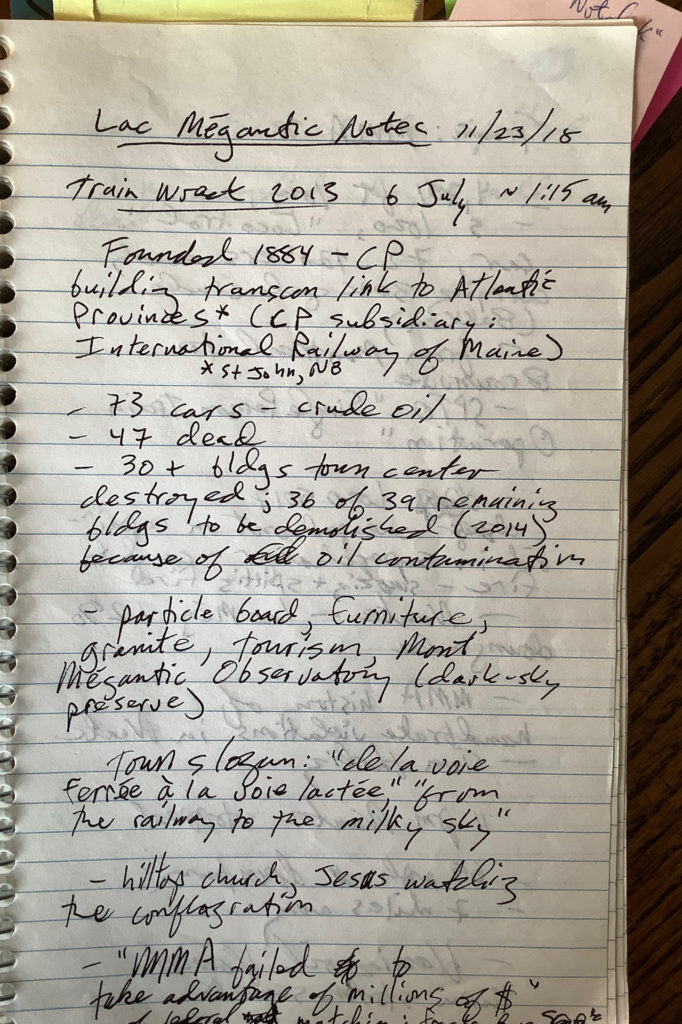

The book has also been a place for consolidating research. At one point, dispirited and angered by the horrific wreck of a runaway train at Lac-Mégantic, Quebec, in 2013, I explored the notion of writing a ballad about the tragedy along the lines of the traditional “Matty Groves,” the Carolina Buddies’ “Murder of the Lawson Family” or Gordon Lightfoot’s “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.”

Entering facts into the yellow notebook from news stories and official reports about that oil-fueled inferno, I learned that the eastbound 4,701-foot train on the Montreal, Maine & Atlantic railroad comprised five locomotives pulling 73 tank cars, each carrying 30,000 gallons of Bakken crude oil. It was left uncrewed for the night on a downgrade seven miles away from Lac-Mégantic and unrestrained by brakes because of human error.

In the middle of the night the train started to roll, careened into town at 65 mph and derailed. The town center was essentially destroyed — flaming oil surged through the storm sewers — and 47 people died.

And the two preceding paragraphs are all that the research has amounted to. Despite repeated attempts, that song remains beyond me. Others have done it, or something like it. But a cautionary tale lies in the example of an Ontario punk band whose “Bend the Iron” not only gets key facts wrong, but uses Lac-Mégantic essentially as a means of what you might call cynicism-signaling.

“I can’t imagine a more insensitive way to talk about an event that devastated so many people,” wrote a reviewer for The Voice, the Athabasca University student newspaper.

I wouldn’t have made that particular mistake, but there are many ways to screw something up. So in that case the yellow notebook served me well, reminding me that as a songwriter I’m best off sticking to my immediate concerns.

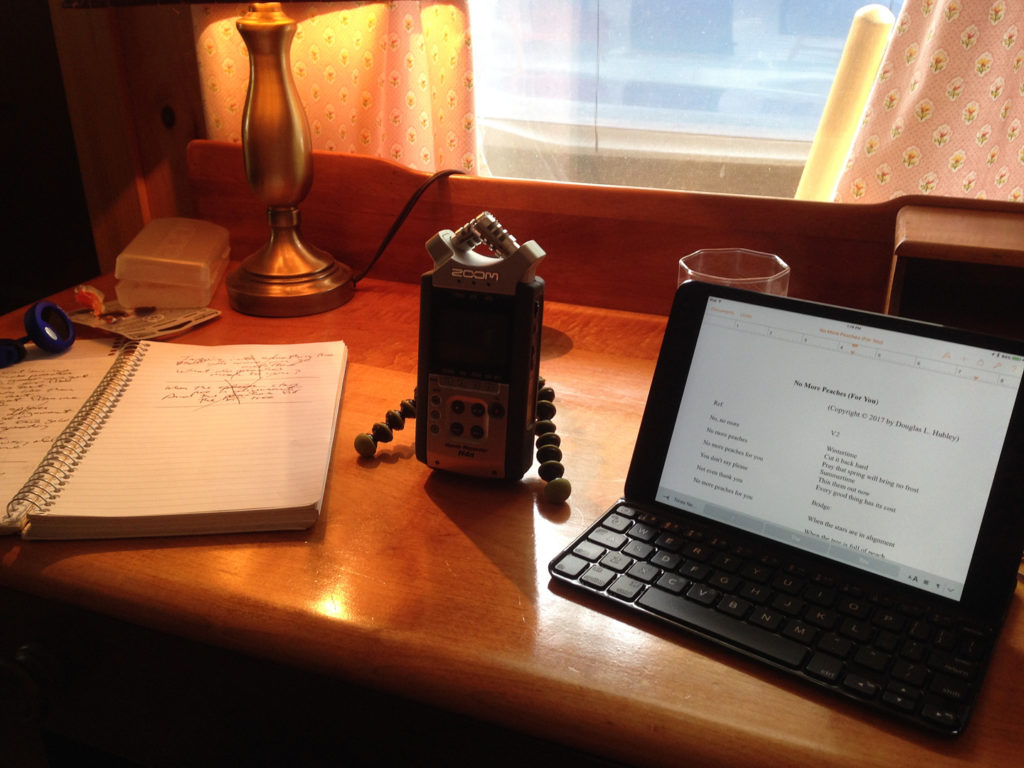

On the whole, I’d call the Chandler Method a success. It has been the incubator that hatched every song of mine since 2016. As I’d hoped, it has kept my mind engaged in the work of songwriting when it would have preferred to wander. (And it has provided another Notes From A Basement idea.)

The only downside to the yellow notebook is an unintended consequence of its design. It’s a problem that I’d sensed in an inchoate way for a few years, and that I finally identified while sitting with the notebook at a kitchen table in New Mexico.

I was stuck on a new lyric — nothing unusual there — and paging randomly through the old Earthwise, looking for traction. But suddenly what I saw there, instead, was 12 pages of unrealized song ideas, many additional couplets and verses that showed no way forward, and still more fragments and false starts dating back to what seemed like a whole different life.

It was a ghost-of-Jacob-Marley moment: While he wore the chains he forged in life, I carry around 150 spiral-bound pages of dead-ended songwriting.

Back in 2016 when I was planning the new and improved songwriting notebook, it hadn’t occurred to me that all the material that would end up on those pages, each phrase and fragment scrupulously annotated with the date and place of conception, could accrete into something that was less like a helpful resource and more like a catalog of failures.

It’s reasonable to wonder where the line falls between productive songwriting practices on the one hand; and on the other, neurotic habits of list-making, idea hoarding, date-and-place notating and so on — activities that look like work, feel like work, take up time like work, but result in a big ink bill and no new songs.

Well, as “Mr. Special” demonstrates, even an old germ of an idea can come to life under the right conditions. And it’s certainly true that every song I have finished since 2016 has roots in that yellow notebook. So probably all that really does justify the creative conceit that the notebook represents.

The desolate moment in that Santa Fe kitchen passed. But I don’t forget it. The old really can give rise to the new, but the trick is knowing which is which.

Notes From A Basement copyright © 2012–2023 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.