End of a Long Dry Spell

Day for Night performs “Bittersweet” at Andy’s Old Port Pub in March 2016. Videographer: Jeff Stanton.

And they’re handing down my sentence now

And I know what I must do

Another mile of silence while I’m

Coming back to you

— Leonard Cohen, “Coming Back to You”

Visit the Bandcamp electro-Victrola!

Some people write a lot of songs

or write songs quickly or both.

They can find inspiration in a hangnail and can scarcely handle all the melodies welling up from within.

The public debut of “Bittersweet,” and my debut with the mandolin, took place at the Portland wine bar Blue in August 2010. Hubley Archives.

But they do modestly assure you, while talking about their productivity, which you didn’t ask about, that they’re only conduits for The Music.

I’m not one of those songwriters. I admit that I envy them. It’s important for me to think of myself as a songwriter, and I do qualify, but three songs make a very big songwriting year for me. And I haven’t seen one of those in decades. Well, there’s always hope.

I’ve accepted my sluggish writing pace and have even had a few peaceful years of not feeling compelled to understand it, although working on this post does reopen the question. Excuses come readily to hand; the real reasons, not so much. It’s a curious way to proceed.

I nevertheless do have a working routine that results in songs, however few and far between. This routine matured as I found my way out of a barren period that lasted for an alarming 11 years.

Gretchen wears a crown of Peaks Island bittersweet in this public relations selfie from October 2010. Hubley Archives.

I never gave up on songwriting during those years. I just never finished any songs.

It was a trek through the desert that lasted from 1998’s “Caphead” — the best song that I wrote for the Howling Turbines, or I should say “the better song,” since I wrote only two for that band — to early 2010 and “Bittersweet,” the first title I wrote for my current ensemble, Day for Night.

If my excuses for not writing aren’t interesting and the root causes are hard to ascertain, it is nevertheless clear that what roused me again was Day for Night, the acoustic country duo comprising Gretchen Schaefer, my life partner inside and outside music, and me.

After fumbling around for three years after the demise of Howling Turbines, in 2004, we had settled on a musical approach and were getting some gigs. We loved the classic country we were doing; but at the same time, having a band that, for the first time in a few years, was doing more than walking in place relit the pilot light for my songwriting.

That is, there would be a home and an audience for my songs — not to mention the considerable formal challenge, which I’m still trying to master, of creating credible songs for a two-piece band playing vintage country, with its “three-chords-and-the-truth” aesthetic.

My first songs, way back there in the late 1960s, had a country (-pop-folk) feel because that’s what idols like Neil Young and Tim Hardin were playing as they infected me with wanna-be disease. (Making me more susceptible was the dawning realization that emotions and relationships are dealt with more easily through guitars and microphones than anything as debilitating as personal communication.)

But if I was young enough to want to copy my idols, I was willful or perverse or ornery enough not to be direct about it. (Shades of that personal communication thing.) I frequently had to make things too complicated, which succeeded more often with lyrics than melodies, which in my case tend less to well up from within than to be wrung from pieces of sandstone.

That complicating tendency lasted a long time. It actually found a home in the early 1980s, 12 years into my songwriting career, with one of my bands: the Fashion Jungle. The FJ was predicated on original material, was musically capable and, successor to a hopelessly eclectic covers band, was stylistically agnostic.

A song like “Little Cries,” with its chromatic chord progressions, rambling architecture and elusive home key, was definitive Fashion Jungle. It was also about as far from country you could get and still be singing about feigned love and fake orgasms.

But the FJ introduced me to a certain discipline of songwriting. In the belated-but-potent Portland, Maine, New Wave scene, we had to perform our own songs for the sake of credibility and self-respect.

None of us was prolific — I wrote the most, if that tells you anything — so in the early days, we agreed to each bring in something original at regular intervals, even if just a lyrical fragment or a chord progression. And a few good songs resulted from that practice.

Anyway, I have managed to simplify some as the years roll on, and by the time I was ready to finish “Bittersweet” I was able to winnow it down to a mere six chords and the truth.

That was four years after I started it.

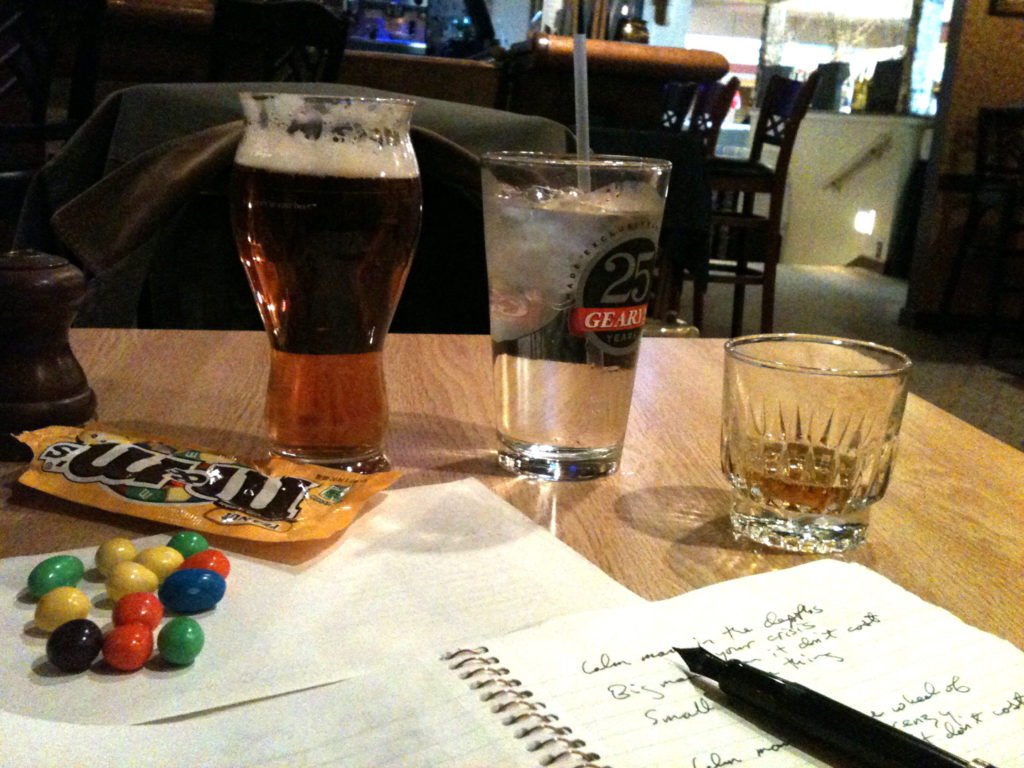

Writing “Where Was I” in the bar at the Senator Hotel in late 2012. You work your way, and I’ll work mine. Hubley Archives.

“Bittersweet” doesn’t precisely exemplify my current songwriting practice but, to paraphrase the Staples Singers, it took me there.

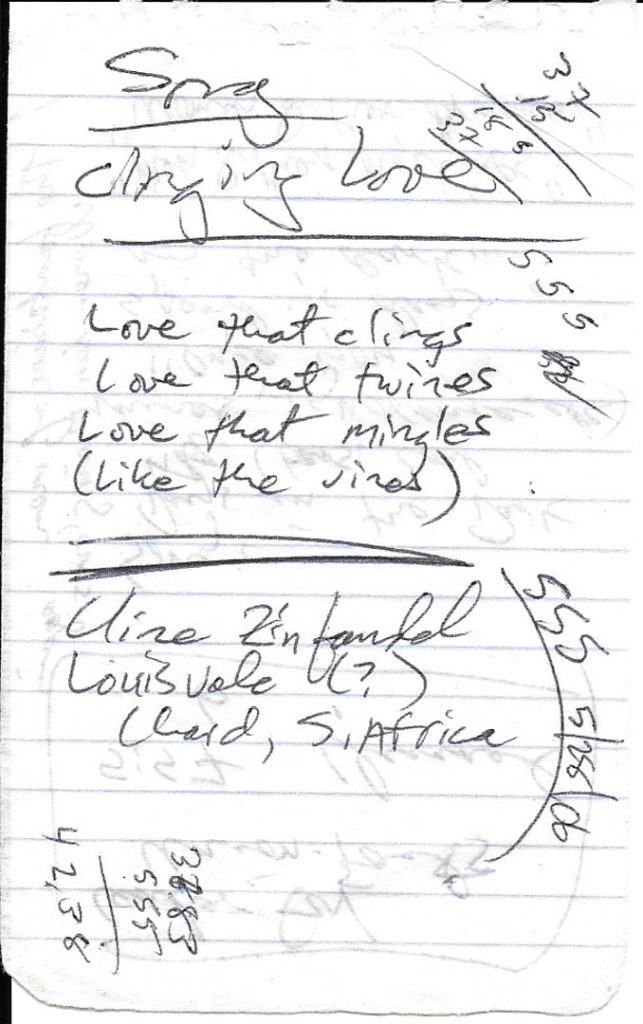

Inspired by the Carter Family, the idea of a song about love that’s like a destructive clinging vine probably came to me during one of my noontime rambles around Lewiston, Maine, where I work. That was in May 2006.

A month later, loitering in Boulder, Colo., while Gretchen attended a conference, I undertook the exercise of sitting in coffee shops and writing a bunch of crap just to keep the muscles limber in case the muse was lurking nearby. (Poetry by Leonard Cohen helped prime the pump: His Book of Longing was new that year.)

That process produced one useful verse for what I called, at the time, “Clinging Love #1.”

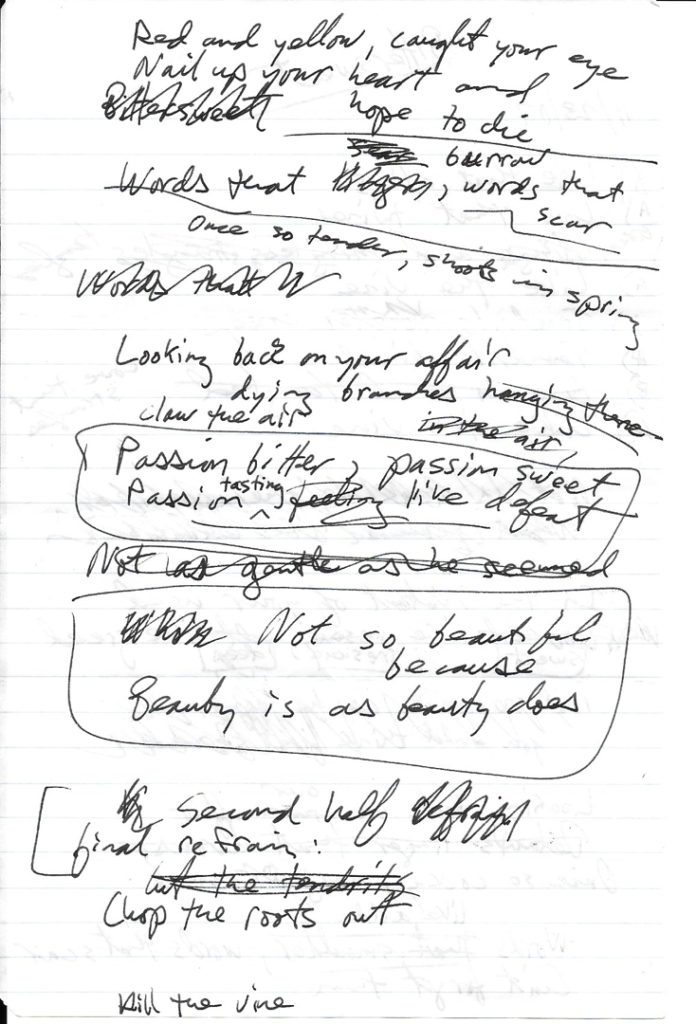

A year and a half later, I somehow arrived at the actual title: “Bittersweet,” named not for the flavor profile, but for the imported invasive vine that makes such pretty berries, strangles the native trees and provides the rare justification for using Roundup in your yard.

Having a metaphor to work with opened the cupboard to a lot of useful imagery, which I pillaged in a hotel room on a freezing evening in Manchester, N.H., 17 months later, in November 2007.

Gretchen was reclining on the bed, coming down with shingles and reading Georges Simenon. I was in a chair with a notebook belaboring “Bittersweet” at length, fueled by Jack Daniels highballs and a songwriting urge stronger than it had been in years.

Since “Bittersweet,” I’ve come to recognize these scribbling sessions as the most exciting phase of songwriting — when they pan out. It’s about inspiration, but it’s not just about being inspired: It’s about capturing inspiration, converting it into a thing, a product.

This phase works better, for me, away from the house and its distractions. (Home is where I finish songs, which is largely an editorial process.) I generally go for the big scribble in cafes, bars and, as in Manchester, hotels.

Hotel rooms are especially good for working on melody as well as lyrics. Composing music must be private (all that sandstone-wringing is unseemly), while writing lyrics can be public.

Manchester scribbles, part one. The letters down the left side were an attempt to impart a rhyme scheme. Be glad I’m not showing you the page where I listed all the words that rhyme with “bind.” Hubley Archives.

In fact, while working on lyrics it helps to have people around. Not too many: just enough to stimulate the socially attuned areas of one’s brain, which can then helpfully suggest behaviors or even stories that can feed a song lyric.

Booze helps, too — until it doesn’t. That was the case with “Bittersweet.” After a couple of hours of graphomania, I felt like I’d left the lyrics in a pretty good place and would get back to it right away.

Well, I got back to it two years later. The idea was still powerful, but the scribbles in my Bob Slate notebook didn’t add up to a whole lot.

Nowadays, at least when I’m trying to write, I drink judiciously, striving for a delicate balance between freeing, on the one hand, the lyrical brain, and on the other, the inner jerk. Cocktails are too small and strong, but nursing a boilermaker or two glasses of wine works out fine. (A bag of M&M Peanuts does no harm, either.)

In the scribbling phase, I’m not looking for finished lyrics, but instead for words in which the finished song lies waiting: maybe a musical setting, definitely a plot, some catch phrases to make it memorable, the right blend of pithy lyrics and words that just advance the story.

(It can’t all be poetry, because singers and listeners alike will choke on that. In fact, singing didn’t start out as words and singers don’t always need them: My goal is to someday write a song that has some well-placed woos or la-la-las.)

So, that’s the ideal. But I can write pages of rhymes and never close in on any of that stuff. (30 years is not an extreme amount of time for me to carry a half-finished lyric around. When it gets to be 50, I may have to find a different outlet.)

But when I can push a lyric to the point where there’s a song discernible within it, my rule — ever since “Bittersweet” — has been to just finish the damned thing. Which, of course, I should have been doing all along.

And which, with “Bittersweet,” I did in January 2010. Sitting at the dining table on one gray cold day, I polished off the lyrics in one intense session. In the basement studio on a different cold gray day, I puzzled out and recorded the music.

And I was a songwriter again . . . just like that.

Tendrils Reach

Three songs written by Doug Hubley and performed by Day for Night, available in the Bandcamp store.

- Bittersweet (Hubley) As described above, the song that broke a long dry spell for me as a songwriter. An invasive vine becomes a metaphor for clinging destructive love. Performed at the 2016 Cornish Apple Festival.

- Stranger Wherever I Go (Hubley) New in spring 2016, this is pretty much a summary of my role in society. Another recording from the 2016 Cornish Apple Festival.

- The Ceiling (Hubley) The first song I wrote for mandolin, as well as my contribution to country music’s illustrious history of songs that are about parts of a room. Also, something of a “hit” for Day for Night after its publication online . . . bringing me three cents in streaming fees every month or so.

“Bittersweet” and “The Ceiling” copyright © 2012 by Douglas L. Hubley; “Stranger Wherever I Go” copyright © 2016 by Douglas L. Hubley. “Notes From a Basement” text copyright © 2012–2017 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.

Very insightful, particularly on the process.

Pingback: Notebooks From A Basement - Notes From a Basement