The Beginning of the Living End . . . The Downtown Lounge

NOTE: An abridged version of this article was first published in the Jan. 17-30, 1990, issue of The Face, a tabloid newspaper focusing on music in Greater Portland. Please note that facts have changed to protect the integrity of the space-time continuum.

By Doug Hubley

In this era of nostalgia chic, let’s give the Downtown Lounge its due:

Just about 10 years ago, a young man with a Beatle haircut and a passion for underground rock approached a band between sets at the Friendship III.

The Friendship III was a bar, medium tough, on a Commercial Street site that’s now a parking lot. The band was the Mirrors, a quintet that tried, sometimes successfully, to do every kind of rock and roots music there was. I played lead guitar and did some of the singing.

The young man was Will Jackson, a staffer at the University of Southern Maine and a part-time deejay. He told us he was planning a series of “Punk Nights” at the lounge of a local hotel and was looking for talent. The Mirrors were qualified by a repertoire that covered the Velvet Underground, Elvis Costello and the Fabulous Poodles along with George Jones, Eddie Cochran and Bessie Smith.

The hotel was the Plaza, at a Preble Street site that, too, is now a parking lot. The lounge was the Downtown Lounge: a name that glows neon in local rock legend.

Jackson’s first Punk Night in January 1980 was a smashing success, but its significance transcended the fact of drawing nearly 300 hipsters to a dive on Preble Street: in fact, the Lounge launched an alternative rock scene that today supports a couple of Portland nightclubs and makes this city a valued stop on the national tour circuit.

Portland would probably have something like that scene today even if there had been no Downtown Lounge. Says Jackson himself: “It was something waiting to happen, just as in ’76, punk was waiting to happen. I mean, if I hadn’t done it, somebody would have to have done it. It was bursting at the seams … ”

But the fact is that Jackson, now a resident of Seattle, Wash., did do it. As manager of the Lounge, this oasis of hot cool in a decrepit hotel, Jackson established progressive rock in Portland.

His creation also gave a number of musicians, this writer included, a badly needed creative shot in the arm. And it marked the beginning of the end for Maine’s stubborn resistance to contemporary pop culture.

Finally, in giving a hungry audience the new music otherwise unavailable in Portland, the Lounge molded a “club” of enthusiasts whose banner is faded but still flying. And the Lounge’s demise proved that the best intentions couldn’t win more support from that small community than it had to give — a lesson that always needs relearning.

They say that during gestation, the development of the human fetus mirrors the evolution of animal life, from the simplest microscopic organism to the infant person. Similarly, the gestation of the Downtown Lounge mirrored in miniature the evolution of Maine urban entertainment.

And what a mother the Plaza was. Born the Hotel Brunswick in 1914, the building was renamed the Graymore in 1920 and in 1923 was expanded to the configuration known to Lounge lovers. It became the Plaza in 1966.

Through name and ownership changes, one thing remained constant during the hotel’s existence: the slow descent from the Hotel Brunswick’s middle-class respectability into the dimestore-mystery setting that was the Plaza.

From the 1940s on, fires, renovations and changes of ownership proclaimed successive “new beginnings” for the Graymore, while the tally sheet of liquor violations, exotic-dance scandals and even copyright infringement cases got longer and longer. Up through the ’60s, the Graymore’s ballroom and lounge — sporting monikers like “The Beachcomber,” “The 21 Club,” “The Terrace Room” — offered a tawdry and fascinating variety of ninth-rate burlesque acts.

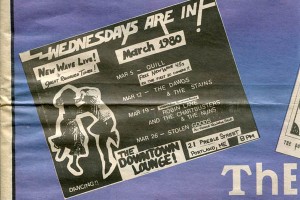

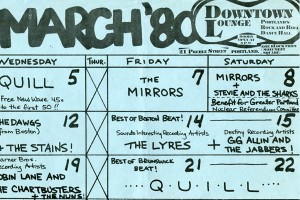

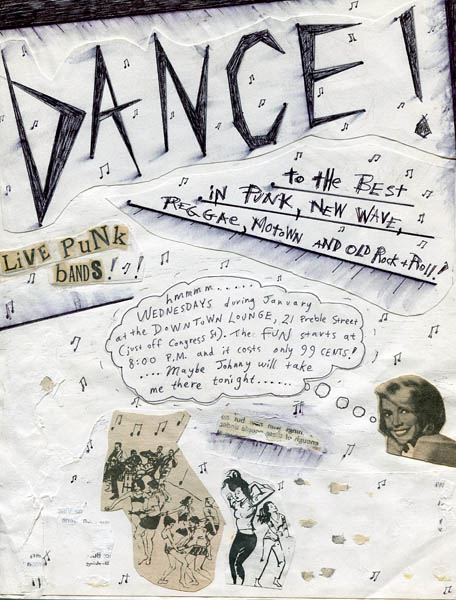

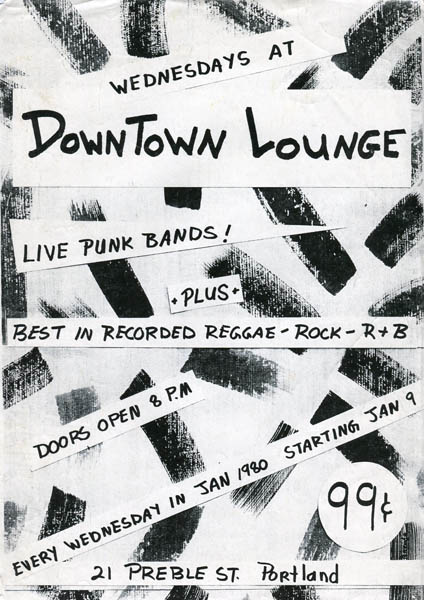

Copied from the cover of the Face magazine, a Downtown Lounge poster. Will Jackson started with Wednesdays as he used the DTL to open a wormhole between pokey ole Portland and the rest of the music world.

Say, whatever happened to French singing star Albert Cerf, exotic dancer Misty Knight, funnyman Red Kane? Where are Danny O’Day and Laurel Sands? And where is Ava, “a breath of Spain”?

Ava and her fans would come and go, but the entertainment that always got the biggest billing in tales about the hotel was the kind that happens offstage and the ushers wear blue uniforms.

Fred Muccino, erstwhile jazz drummer and car dealer, bought the Plaza in the early 1970s. He gave the bar and ballroom names like the Windjammer and the Ice Cube Lounge and brought in country & western bands, which Muccino calls his biggest money-makers ever.

(My first Plaza experience was in 1976, when Giz Daniels, now bassist for the Upsetters, hired me to play lead guitar in a pickup band behind Kenney Freeman, Maine’s answer to Elvis Presley. The stage was dim, the room pitch-dark. My fingers were cold and stiff with fear. Nothing much happened.)

In autumn 1979, Muccino engaged Jim Peterson to manage the lounge. Beginning in 1976 with Jim’s Bar & Grille, Peterson had put his name on a series of clubs whose imaginative booking policies gave the city a taste of the modern world. He redecorated Muccino’s huge ballroom, christened it the Downtown Lounge, and began bringing in local jazz, blues and mainstream rock and disco.

Bringing in, in other words, the tried and true, the status quo, the state of the artless in Maine entertainment. This was not Peterson at his best, but it had the virtue of commercial potential. It was the kind of fodder that had fattened Southern Maine’s live music market to an unprecedented degree by the late 1970s.

Enter Will Jackson. A Connecticut native, Jackson was an academic counselor at USM and a deejay exploring a new-found love for progressive rock: punk, New Wave, and the myriad sub-genres that were growing from rock’s last great flowering.

“Punk hadn’t broken at all in Portland,” says Jackson.

“I confess, I didn’t get into any of that stuff until ’79 myself. And I think part of it’s because I was living in Maine, and I just wasn’t exposed to it … But it was happening, and there was an underground here.”

Jackson was taken by the Lounge, its size, its aura of class gone to seed and its layout, ideal for a dance club: stage surrounded by huge dance floor surrounded by seating on two levels.

“After looking at this place for a couple of months I went to Fred and said, `Let me try something on an off-night, on a Wednesday night.’ I told him what New Wave was, and what punk rock was,” Jackson recounts. The easygoing Muccino agreed.

“So I decided, `OK, here’s our big chance,'” Jackson says. He hired a trio from Brunswick called Quill, “that in retrospect was not real New Wave, but they played fast-tempo stuff that owed more to King Crimson than anybody else.”

Jackson and a friend assembled a poster, depicting a nerdy mad scientist peering at the dancing young folks under his microscope, and plastered it all over town. And thanks to that poster and some adept grapevine work, the first Punk Night — Jan. 4, 1980 — was a winner. Jackson claims that 270 people showed up. “The room was jammed to the hilt. So Fred went, `Let’s keep going with these Wednesdays!'”

Keep going they did, for about a month, with Quill and other local bands drawing big at midweek and Peterson’s mainstream stuff stiffing on the weekends.

Consequently, Jackson says, Muccino ousted Peterson — a portent if ever there was one — and laid Friday, Saturday and eventually Thursday nights on Jackson’s plate.

[Jim Peterson responds, Sept. 6, 2012: “I was never bounced from the lounge. Will was welcomed with open arms — love him. Long before the lounge opened, myself and a prominent longtime Portland businessman struck a deal with Fred to buy the hotel. I would fix it up and open it till I could find someone, and from heaven came Will. Fred became so wishy-washy, we decided to end our business association — too bad, could have been a longstanding venue in Portland, for people like Will and many others. This was all happening in the background….so you see, there is always more to the story!”]

With more nights to fill, Jackson started tapping Boston’s swelling roster of cutting-edge bands, along with “every Portland band I could that was playing original music. I mean, the whole idea was to have it be New Wave and/or original music.”

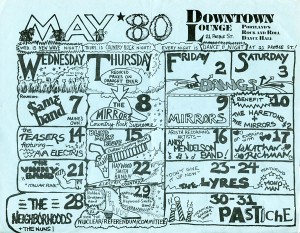

That’s how Portland was introduced to hot tickets from away like Pastiche, Thrills, Boys Life, the Lyres, the Donns, the notorious Lou Miami and the Kozmetix. And that’s how the city happened to look under its nose and see local talent like the Stains, the Same Band, the Haretons, the Pathetix and the Foreign Students.

By April Jackson was able to start bringing in acts of national caliber: Jonathan Richman, Robin Lane and the Chartbusters, Joe “King” Carrasco and the Crowns. He put the strong draws on the weekends, untried acts on Wednesdays and the occasional special billing on Thursdays.

There were benefits, for such causes as the Maine Nuclear Referendum Committee; and oddball concepts, like Corner Night, which featured the Mirrors and two other bands drawn from a thriving social circle based at a South Portland corner variety store.

There were benefits, for such causes as the Maine Nuclear Referendum Committee; and oddball concepts, like Corner Night, which featured the Mirrors and two other bands drawn from a thriving social circle based at a South Portland corner variety store.

People immediately started gravitating to the Lounge and offering their services, says Jackson. A local artist, Nancy Klintz, joined the poster-making effort; what resulted was Maine’s belated introduction to the Post-Modernist, ransom-note cut-and-paste, ironic comic style that’s common currency today.

Supplying canned music were deejays like Richard Julio, whose record store, the Wax Museum, was Portland’s best source of obscure rock during the ’70s; and Tim Warren, a Lewiston youth whose circle pioneered nerdy thrift-shop chic. Warren, who now runs a reissues label in New York, “played unbelievably great music,” says Jackson.

He “somehow was tuned into that camp ethos that the B-52s later revealed to all of us. And we were all discovering the Ventures, TV themes, ’50s rockabilly, ’60s camp bands — we think of them as camp now — like the surf instrumental bands, the bad country bands, all these one-shot wonders; singers like Peggy Lee and the bad imitations of Frank Sinatra.

“Tim was into all of that, and he knew it all.”

The Lounge communalism that attracted Klintz, Warren and many others even inspired one young devotee to bring in her tools and make repairs. “At one point the women’s bathrooms were falling apart,” Karine Odlin recalls. Now the operator of a video lighting franchise, Odlin in those days was a carpenter who took it upon herself to rehang a door in the ladies’ loo.

“We took pride in that place,” says Odlin.

“Faster — louder — more fun!” was the slogan Tim Warren devised for the Lounge, and on a good night it was realized, to the umpteenth power.

For Jackson, the definitive night at the Lounge had Boston’s Thrills on stage. It was “like a fire had started, like energy had spread through the whole place, because there were just bodies moving, sweating,” he recalls. “The band was unbelievably loud and unbelievably intense, and great.”

And when the joint shut down for the night, Jackson says, and the crowd swarmed out into Preble Street, he overheard someone marvel, “I can’t believe they’d let us back into public after something like that!”

That was the idea: transformational experience as imposed by a firestorm of decibels and drumbeats. For me, it took the swirling Tex-Mex of Joe “King” Carrasco and the Crowns to make that connection — the connection with disconnectedness — and I was never again the same. In short, at the Lounge I learned not only how to dance, but why.

And I wasn’t alone.

Suzanne Murphy, a key supporter of the Lounge and today a counselor at St. Joseph’s College in Windham, recalls the night eternal boy rocker Jonathan Richman joined Robin Lane & the Chartbusters on stage. (Lane is the Boston-based chanteuse, now a solo act, who teetered on the brink of a national breakthrough in 1980.)

“Two songs, that’s all,” says Murphy — all Richman needed to work himself into a froth and steal the show from Lane and the Chartbusters. “By the second song he had ripped his shirt off and jumped into the crowd. It was one of those rock ‘n’ roll epiphanies.”

Rumors of such epiphanies drew bigger crowds and, eventually, the press. Maine Sunday Telegram columnist Doug Warren was an early supporter whose awareness of rock music gave him an understanding of the phenomenon unique among his peers. (Though not among his family — his sister Susan was a waitress there.)

Evening Express writers Dyke Hendrickson and Kim Murphy plainly didn’t have a clue what all the weird music and funny clothes meant, but they were favorable, if patronizing. Murphy noted aptly that her only other visit to the Plaza, in 1972, had been to cover the murder of a man stabbed with a screwdriver.

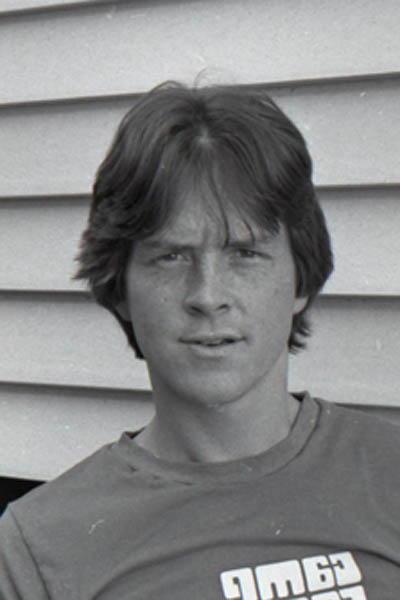

The Mirrors at the Downtown Lounge, 1980. From left: Jim Sullivan, Mike Piscopo, Chris Hanson, Doug Hubley. Concealed by Chris is drummer Ken Reynolds.

The Mirrors got murdered at the Plaza too. Yes, we did play there, several times, and it provided epiphanies small — for example, how much fun a rock band can have when draft beers cost just a quarter and there’s no audience to cramp your style — and great.

In fact, as generous as Jackson was to invite us back several times, we didn’t belong. This made for some unsettling gigs; for example, as the best-established group on the Corner Night bill, we claimed the closing spot — and got killed by the Foreign Students and the Pathetix (the latter a bunch of teenagers in their first public appearance.)

That indeed was a revelation, because it taught us, me in particular, that in our stylistic promiscuity we were pleasing no one by trying to please everyone. That led us over the coming months to start writing our own songs, to focus our sound, and to make it “faster — louder — more fun!” As the Fashion Jungle, we finally realized that goal. By then, though, the Lounge was history.

“There were three or four nights a month that were that intense,” Jackson says of the Quill pogo fests. “And then there were other nights that weren’t so great.”

“The nights when hardly anybody showed up were kind of sad and pathetic,” says Suzanne Murphy. “I mean, you’d get these bands to come all the way up from Boston, and then nobody would come.

“Because Will overbooked. He tried to have live music there so many nights a week. The scene just wasn’t that big, people just couldn’t go out [that often]. I found myself being apologetic to Will –`I’m sorry, I just can’t come see the Outlets this week.'”

Jackson was learning what other Portland clubowners keep discovering anew: Southern Maine’s progressive rock following may be loyal, but it’s also small, poor and often indifferent to booze. At the Lounge, Wednesdays — the weeknight that started it all — became particularly chancy. After Jackson took over the whole Lounge schedule, that night was reserved for new bands that often proved to be “real absolute losers,” he says. “Terrible bands.”

On the weekends, he was booking proven draws for two- night stands. But even the strongest acts, like Thrills or Pastiche, could pull in only enough of a crowd for one lucrative night out of the two.

Ah, reality rearing its ugly head. “I’d get on the horn to these bands and I’d say, `Well, you guys — you get to come up here, I’ll give you 150 bucks a night and you can stay for free upstairs,'” Jackson says. “And they’d go, `Great! Weekend in Portland, a vacation, play for this enthusiastic crowd.’

“And the Dawgs would come and people would love them to death, and then they’d go upstairs and stay in the incredibly seamy, unkempt” Plaza. The beds being a ticket to unknown biological adventure, bedrolls were de rigeur. Some artists, like Robin Lane, refused to stay at the hotel altogether. “She took one look and said, `Get me out of here,'” says Jackson.

But for those of us who didn’t have to sleep there, the sordidness of the Plaza was part of the Lounge’s charm. The rooms, though supplying plenty of fuel for speculation, were unseen by most Lounge patrons, but you could only get to the Lounge proper through the “outer bar”: a dark chamber equipped with jukebox and pool table and populated by seeming rejects from a Tom Waits narrative.

And the scents of faithless sex, comic violence and lives gone to ruin made a perfect complement to New Wave music, its paradoxical link of hedonism and puritanism.

“I loved that whole atmosphere,” says Suzanne Murphy. “I think that was just perfect for the type of music, the kind of rebellious music — it wasn’t part of the establishment, it wasn’t institutionalized.

“I liked the class aspect of the place itself, that it wasn’t gentrified or in any way ‘cleaned up’; it was just what it was. It didn’t intimidate me.”

But if the oil-and-vinegar blend of sleaze and hot music worked as ambience, it was a symptom of trouble. Muccino, says Jackson, refused to either give him a budget for bringing in acts, like the Ramones, that could have put the Lounge on a solid financial base, or to clean up the outer bar.

“It could have been an ideal setup,” Jackson believes. “But Freddy refused to clean it up … He wanted his regulars, because they drank.”

For his part, Muccino (now retired) says that the renovation he and Jim Peterson did in 1979 had tapped him out. He couldn’t afford to heat the place overnight, he says, to say nothing of putting more money into the Lounge. He defends his running of the Plaza, which came to him with “a lot of bad reputation, people complaining it was a fleabag”;

“I tried to run it decent,” he says. “If I thought there was an element of [for example] women doing things, I’d throw them out.”

But ultimately, he explains, “I couldn’t beat the image.” And in fact he put the hotel on the market as the Lounge hit its peak, in June 1980.

Still, Muccino does confirm Jackson’s comment about the outer bar, explaining that, if a bar owner has a group of regulars who, during the course of the day, “spend $25 or $30, you don’t throw your bread and butter away. I had no choice.”

Fred’s eye for the buck and Jackson’s adventurous booking ideas, then, were destined to clash. And the fatal collision, ironically, came in the wake of the Lounge’s biggest night ever.

On Halloween 1980, Bebe Buell and the B-Sides made their debut in a gala costume party at the Lounge. Buell is the hard-rock singer, now scrambling in New York with her band the Gargoyles, who is typically described as a 1974 Playmate of the Month and former inamorata of such rock stars as Elvis Costello.

Buell’s Lounge performance drew an estimated 400 souls to the club and made a lot of noise in the local press. But it proved less a feather in Jackson’s cap than a thorn in his side: Buell’s self-proclaimed “manager,” a newcomer to Portland named Keith Ward, had run the sound for the show, helped with the publicity effort, and ended up convincing Muccino that he deserved credit for the night’s huge success.

Says Jackson, “I walked in a week later to take care of stuff, and there was Keith — this blond, slick guy who used to wear a cape around town — sitting there doing business. And I asked, `What’s going on?’ and he said, `I’m booking the club now … Freddy hired me.'”

When he confronted Muccino, Jackson says, the Plaza owner was evasive, suggesting that Ward and Jackson could collaborate. “So he was trying to balance the two of us against each other, not realizing that we were total opposite personalities. And I had put together an entire November calendar, and this guy was sort of trying to take it away, take over the whole thing.”

Muccino says that falling revenues prompted him to dump Jackson. “The New Wavers weren’t what you call very hardy drinkers,” he says. “They drank lots of orange juice and water, but that doesn’t make the cash registers ring.” Muccino, who at the time thought hiring Ward would turn the situation around, now laments, “I never should have done it.”

Jackson, disgusted, took a hike. He briefly entertained thoughts of canceling all of the November bookings — which included the hugely popular Pastiche and the I-Tones, whose appearances were galvanizing the local reggae following — but refrained.

Yet Muccino’s action did evoke an opposite, if unequal, reaction. Suzanne Murphy, Odlin, Klintz and hip Evening Express reporter Mark McCain christened themselves Committee Against Sleazy Takeovers — CAST — and mounted an informational picket line at the Lounge, handing out leaflets explaining Jackson’s ouster and urging patrons to stay away. The protest drew a mild police response and quite a bit of press, and discouraged the regular Lounge following.

While the I-Tones weekend went well, Jackson recalls, for the most part the Lounge’s clientele fell off, due not only to the CAST protest but to lame-o Ward booking ideas (sock hops?) and to general confusion about the club’s direction. Muccino, demonstrating once again his loyalty to employees, showed Ward the door and asked Jackson to return.

Which he did, to the extent of hiring Pastiche for a final date. And that was that for Jackson and the Downtown Lounge. The club closed its doors just about a year after that first Punk Night.

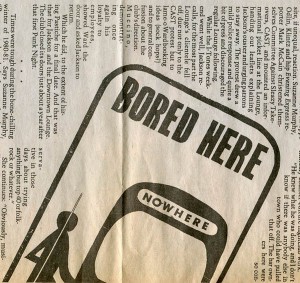

The Greater Portland Transit District used “Board here” signs at bus stops for a while in the ’70s — probably only until this caricature by a Downtown Lounge adherent gained currency.

Times were tough during the bone-chilling winter of 1980-81. Says Suzanne Murphy, “Reagan got elected, the Lounge closed, and John Lennon got shot, all within about a month.” But Jackson and the music lovers he had energized still carried their torch.

Not until 1987 did Portland prove itself able to sustain a healthy progressive music scene, with the opening of two clubs — the Tree Cafe and Zootz — devoted to happening music, and others dabbling in it; but the flame kept burning

right through the interim.

It lit the parties Odlin and Murphy threw at their Gray Street apartment (where I realized that you were allowed to dance by yourself); it sparked the dances organized by Heidi Wolfe, proprietor of the New Wave boutique Tijger, in a warehouse on Union Street. As the years went by you could find it at Kayo’s on Wednesday nights (Will Jackson booking), at the Landing on Mondays (Jackson spinning the discs), at Jim Peterson’s Neighborhood Cafe on Danforth Street (now the Tree), at the Hu Shang on Exchange Street (deejay, Will Jackson), at the Checkerboard Club (now the Tree).

And you could and can find it at Geno’s Pub, the Brown Street cavern where progressive rock, minimal upkeep, an olde Portlande setting beneath Bernie’s Fashions and plenty of liquor add up to a close simulation of the Plaza’s peculiar atmospheric formula.

(And what of the Plaza? Muccino opened a big band jazz club in the Lounge space in 1981. McCord’s flopped, and a fire and the building’s sale to a major real estate developer consigned that hallowed ballroom to history. The building changed hands a couple more times and was razed in 1985.)

But if Geno’s is the club most likely to give you Lounge nostalgia, Zootz and the Tree have the sharpest spots on the local cutting edge. Zootz, run by Kris Clark, specializes in recorded dance music with the occasional live act; the Tree, run by longtime Portland entrepreneur Herb Gideon, has brought a Who’s Who of national-class underground music to Maine. The Tree also has the honor of being Jackson’s last stand, since he did some booking for Gideon this year and last before he and his wife, Lisa Ashe, headed West in October.

Suzanne Murphy does not agree that something like the Lounge was inevitable, Jackson or no. She believes that “the reason it happened is because one person, Will, had all the right characteristics.”

In a nightclub scene slavishly devoted to Top 40, blues and limp country-rock, Murphy says, Jackson had the right combination of nerve, credibility and smarts to make a determinedly counter-culture nightclub work. “He knew what he was doing, and I don’t know if there was anybody else in town who could have pulled that off. The bar owners here were so conservative in those days about trying anything but Top 40 or folk-rock or whatever.”

She continues: “Obviously, musically it just gave a place, a real home to that kind of music, instead of trying to beg and convince other bar owners to `Please, book this kind of music — it really will draw people.’

“So it also gave, obviously, a home to the fans of the music, who were going to Boston all the time. It saved us money,” she adds, laughing. “And then it became a place where you could go by yourself, because you knew you’d see people you knew, and it was a very community-oriented scene, and not a pickup scene, not a heavy drinking scene. Not anything but fun and music and dancing and friendship.”

Ah, what a friendship it was (still is). One more Jackson tale, concerning the band Pastiche, something like Boston’s answer to Roxy Music and clearly the band of that particular moment:

“Every time they played, they did `The “In” Crowd,’ usually as an encore,” Jackson recounts. “So, 1:15 in the morning, people trying to clear away the glasses, the band at its peak: “I’m in with the in crowd’ … and the whole crowd is like, `Yeah!’

“They’re dancing with their hands up in the air. `Yeah! We are the in-crowd!’ That was it, you know? There wasn’t a more `in’ moment in history, for my money … This was the in crowd.”

Pingback: » An Old Friend I Happened to See Notes From a Basement

Was looking on the Internet for Herb Gideon and found him connected here. I am Erika (Ricky/Riki from Bard) Donneson. Came to Maine in 67, in 1971 lived at 97 Danforth Street when Herbie bought it, then lived with Steve Priestley and his brother Jim, formed a free style jazz trio, played all over Portland, eventually in the house band of Raoul’s Roadside Attraction when Randy Morabito was mgr. of the blues jam. Longtime friend of Chris Grasse. I was known for congas and dance.

Eventually studied music with John (Doc) Hadlock when he and drummer Merrill opened a Percussion school in Scarborough, Doc lived in the driveway of my house in Saco that I bought in 1984. NEED TO FIND HERB GIDEON.

I moved to Portland in 1980 and began working at Sweet Potato. We had free cover and drinks on trade at the bars.

What a fun music scene. Will was, and I hope still is, a fun energetic guy!

Nice story…thanks.

Thanks for reading and writing in, Kevin!

Hi Doug found this article and brought back memories playing for Kenny Freeman in 1975 with part of my band JECKL my band was still rehearsing and Kenny needed a drummer and Bass player. As you know I played drums with you in high school. The first night I played there the tables were actually nailed down and somehow a fight ensued tables thrown drinks flying and Kenny said keep playing and we went into Wipeout!

Larry Zellers

Hi Larry! Thanks very much for your comment. Sounds like a wild night at the Plaza — much more like what I expected the time I played there with Kenney Freeman. He was one of those Portland personalities of the kind we don’t seem to have any more.

I was a teenager living in Brunswick at this time; too young to get in. I was friends with Quill guitarist Reggie Hunt’s younger brother, so I heard about the scene via him. The Same Band also hung out at the bike/ skateboard shop I worked at. Later, Heidi Wolfe and her boyfriend Kent Schiffman somehow made it up to skate the half pipe in the back lot of the bike shop. Heidi would bring records, t shirts, magazines, and buttons to sell us – she was like a punk Peace Corp.

-Snook

Hi Snook! Thanks for sharing your story — Best, Doug

Snook? Best wishes to you from tracey