Three in a Match, or the Jungle at Jim’s

Skip the blah-blah! Go directly to the music!

In January 1982, I did something I’ve regretted ever since: I got rid of my sunburst 1976 Fender Telecaster.

It’s true that Tellies are a dreadful cliche in Nashville country music now — which leaves me a little ashamed that I still want one. Steve Cropper, Don Rich, James Burton, Waylon Jennings; Gram Parsons and Chris Hillman on TV with their twin Tellies (a fond dream I have for my current band, Day for Night) — how could I NOT want one?

I drove to a music store on the river in Cornish, Maine, to trade the Fender. The car was my beloved 1973 Sumatra Green VW Squareback. It was less beloved than usual on that sortie because exhaust was billowing into the cabin, so I had to drive with the windows open. As noted, it was January in Maine, back in the pre-climate-change days when January in Maine meant cold.

The Telly was my first Fender in the succession of electric six-strings: the Kent something-or-other, which was the first guitar I owned; a Rickenbacker 360, which a friend now has; a Gibson SG; the Fender. After the Gibson, I wanted a guitar that would stay in tune, and not lose its tonal character when I backed the loudness down. The Fender not only did those things, but was extremely playable in that inimitable Fendery way.

And then I had Buckdancer’s Choice fabricate for it a black pickguard, with a fine white outline, that redlined the coolness gauge.

A shot from a 1982 Fashion Jungle publicity shoot. From left, bassist Steve Chapman, drummer Ken Reynolds and guitarist Doug Hubley. Photo by self-timer/Hubley Archives.

But by 1982 I was worried that the Fender lacked the tonal variety that I believed I would need now that my band, the Fashion Jungle, had shrunk from four to three members and the classic minimalist lineup of drums, lone guitar and bass. And I couldn’t afford a new guitar without a trade-in.

So, practically crying, I traded the Telly toward a new black Stratocaster. Then drove back through the frigid air and failing sunshine, enveloped in VW exhaust, to South Portland.

Regrets aside, the trade was the right thing to do. There were gaps in the FJ sound that it filled well, as its three equally powered pickups afforded a much broader spectrum than the Telly’s quaint lead-and-rhythm arrangement. (Which doesn’t stop me craving one, though I have played Strats ever since.)

Perhaps my sadness at losing multi-instrumentalists Jim Sullivan and Mike Piscopo was sublimated into fears that a three-piece FJ would pale in comparison to the founding lineup, in which Mike and Jim could color songs with fiddle, sax, organ or a second guitar.

But (as usual) I needn’t have worried. This new Fashion Jungle was sui generis. It was a whole new thing, even if we did cling to the original quartet’s original songs for a year after bassist Steve Chapman joined, in autumn 1981.

As it turned out, Steve’s presence was decisive. He rendered the whole question of instrumental variety much less exigent (although we did later add a keyboard player, and were glad to have her).

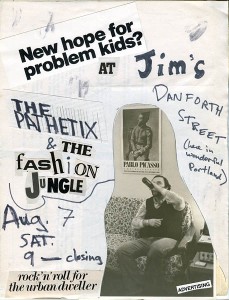

One of my typically slapdash band posters, featuring our friend Alden Bodwell draining the bottle. An early performance by the three-piece Fashion Jungle, sharing a bill with old friends the Pathetix. Hubley Archives.

As noted in this space previously, Steve is an assertive bassist who can both, if you will, ride the wave and be the wave — meaning, he was able to satisfy the bassist’s obligation to anchor a song while eloquently building its structure out in other directions. In the music presented below, all recordings from a 1982 performance at Jim’s Neighborhood Cafe, listen to:

- The roar he creates during the instrumental section of “Dumb Models.” Steve downplays the rounded midtones of the bass guitar spectrum in favor of the extremes of high and low.

- The path he makes through the chords and melody of “Je t’aime,” especially in the bridge.

- The razor-edged tone in “Little Cries,” an analog to the vitriol of the lyrics.

- His lines during the middle rave-up in “She Lives Downstairs,” expressing a melodic sense that to me, anyway, became synonymous with the Fashion Jungle.

- And the way he takes on the signature riffs, originally devised for the Farfisa rock organ, in “End of the Affair” and “Nothing Works.”

How did this new ingredient affect the chemistry of the band? I can’t say that I discovered dramatic new musical directions in the trio FJ — though I did learn to play less guitar, paradoxically enough in this band with fewer instruments. Steve and Ken were so solid that my most effective contributions often contained the least sound. The trio format, I realize only now, in a way suited my guitar approach well: I’m not talented or domineering enough to want to play a lot of lead, and in some ways I can find more interesting things to do as a rhythm guitarist.

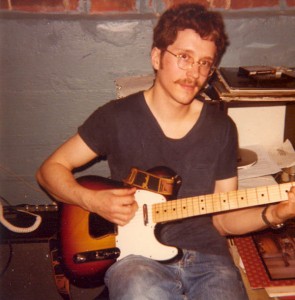

DH with the brand-new Fender Telecaster in 1976 — photographed in Ben and Hattie’s basement, natch. Ampeg guitar amp to my right, Emmylou Harris’ “Elite Hotel” to my left. Hubley Family photo.

Vocally, too, I was changing, but I’m not sure why. Could have just been maturity, as I became less reliant on imitating idols (the Leonard Cohen imitation was still to come, a decade later). And the songwriting continued as before, as Steve proved to be a stimulating peer in that realm.

I think the definitive change involved drummer Ken Reynolds. The trio FJ set him free, the culmination of a process that had begun with the original FJ. As I’ve recounted here previously, the FJ had emerged from another band, the Mirrors, whose mellow commercial tendencies proved too restrictive for our roiling male hormones.

In the founding FJ, Ken could fully inhabit the hard-driving inventiveness he had only been able to visit before. And in the FJ trio, propelled by Steve and with spaces to fill, Ken’s faster-louder sound hardened into his signature style, one that helped define the band for most of the 1980s.

All but one of these Fashion Jungle recordings were made during a performance at Jim’s Neighborhood Cafe, on Danforth Street in Portland, on Oct. 6, 1982. The crowd noise is almost worth the price of admission. Recorded in two-track on a cassette machine: Low fidelity is our trademark! The exception is “Old Masters,” which is old and new. Read on.

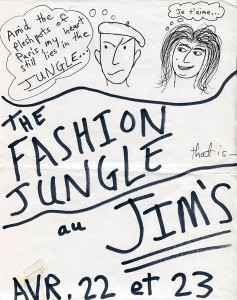

For another Jim’s Neighborhood Cafe gig, a poster subtly promoting my new song “Je t’aime.” Hubley Archives.

- End of the Affair (Hubley) I was losing my voice on this evening, but never quite lost it. Listen to Ken’s embellishments on this breakneck number, one that stayed with the FJ to the very end.

- Dumb Models (Hubley-Piscopo-Reynolds-Sullivan) Listen for the trippy flange effect on the Rickenbacker 12-string — and that bassy roar referred to above.

- Je t’aime (Hubley) Brand-new for this gig, this song is an interpretation, somewhat unfair, of an affair I had with a Swedish girl in 1976. For the song, nationalities were changed because, well, Paris, you know. Although, or because, I distorted the facts to save face, I still regard it as one of my best songs, and it cropped up again later in the repertoires of the Boarders and Howling Turbines.

- Little Man, Long Shadow (Hubley) The lyric, inspired by a true story, likens a spurned lover to a terrorist. This song didn’t stay long in the repertoire; so much for riding on Bow Wow Wow’s coattails.

- She Lives Downstairs (Hubley-Piscopo-Reynolds-Sullivan) The backing vocals are rough, but the new arrangement, with an added and oddly obsessive instrumental break, is an improvement over the 1981 version.

- Nothing Works (Hubley) Ska madness, as Steve picks up the signature line that Jim Sullivan used to play on the organ. The crowd goes wild as we stagger on to the end. What the hell did I know about Chrissie Hynde’s problems, anyway? Or the Red Sox, for that matter?

- Little Cries (Hubley) Breakneck! Lacking saxophone for the instrumental break, we just bomb through it.

- Old Masters (Chapman) Because this set is dominated by material that I wrote or that came from the founding FJ, I wanted to close this set with a number by Steve Chapman. “Old Masters,” a commentary about the relationship between technology, culture and fine arts, was the first song with lyrics that he contributed to the FJ. We recorded the instrumental track in 1982; Steve added the vocals in summer 2012.

Copyright © by Douglas L. Hubley: “Little Cries” (1981), “Je t’aime” (1983), “End of the Affair” (1984), “Little Man, Long Shadow” (2012) and “Nothing Works” (2010). All rights reserved.

“Dumb Models” and “She Lives Downstairs” copyright © 2011 by Douglas Hubley, Michael Piscopo, Kenneth Reynolds and James Sullivan. All rights reserved.

“Old Masters” copyright © 1982 by Steven Chapman. All rights reserved.

Text copyright © 2012 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.

Pingback: » Other Voices: The Fashion Jungle, 40 Years Later Notes From a Basement