Fashion Jungle: Late to the Party

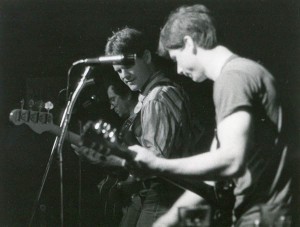

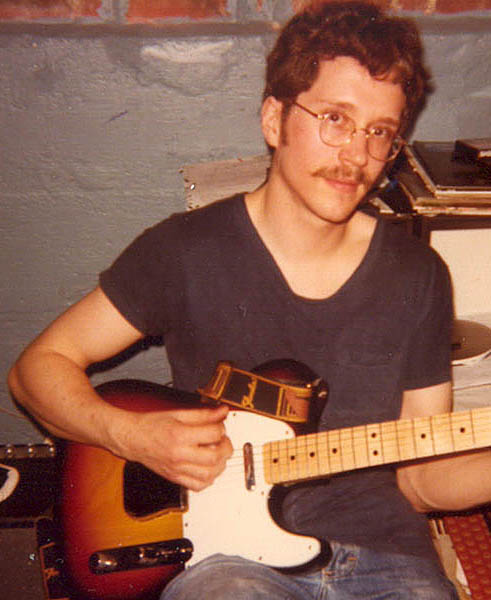

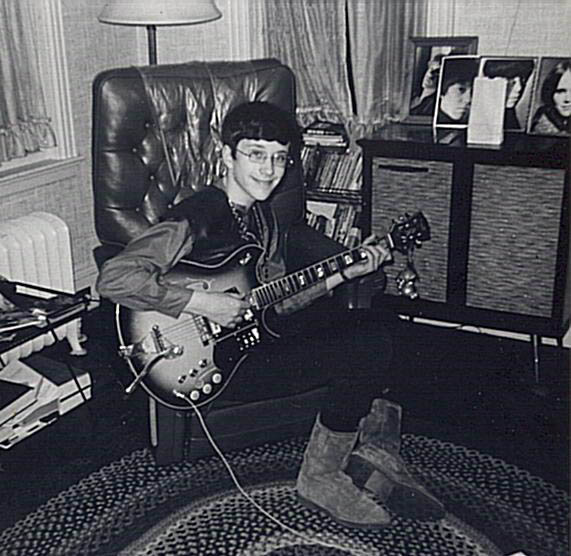

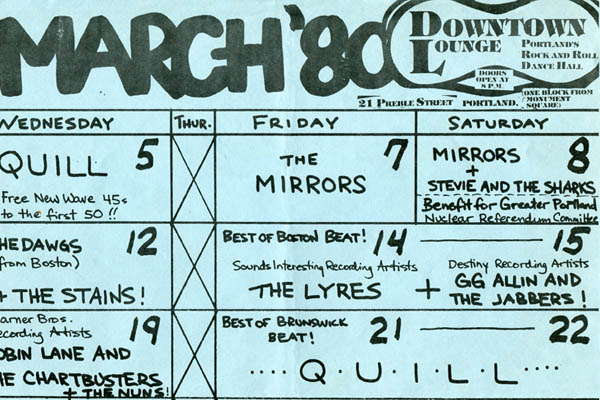

The Mirrors had two Downtown Lounge dates in March 1980. I lost my voice for the second one. Hubley Archives.

New Wave music* finally hit the beach in Maine around 1979-80.

In those days, there must have been other places in Portland where the hip and cool met and mingled, but the first one I heard about was the Downtown Lounge, the legendary dance club in the Plaza Hotel, located on Preble Street about where the Public Market is now (itself fodder for nostalgia at this point; whole other story).

TLDR? Go straight to the Bandcamp EP!

If the Mirrors’ metamorphosis into the Fashion Jungle was bound to happen, there was no more efficacious catalyst than the DTL during its brief heyday in 1980. Suddenly there was a place in Portland where you could hear the newest and nowest sounds from the Northeast — Jonathan Richman, Robin Lane & the Chartbusters, Lou Miami and the Kozmetix. More important, impresario Will Jackson was so desperate for talent that local bands who previously couldn’t get arrested in square old Portland suddenly had a home.

The Mirrors were a cut above the couldn’t-get-arrested category, and we played the DTL a few times: among them an anti-nuclear power benefit, a “country night” with 25-cent draft beers for the band (no audience, but we had a blast) and Corner Night, when, as previously described in this space, the up-and-coming Foreign Students and Pathetix ate our lunch.

What the DTL did — for the Portland music scene, for four of the five Mirrors and for me personally — was provide one of those rare and so exciting views to not only a new and better world, but one that was completely accessible. There was absolutely no reason Portland couldn’t have cutting-edge music. No reason that Mike Piscopo, Ken Reynolds, Jim Sullivan and I couldn’t take our places in a scene where loud fast music about sex and politics would be embraced.

And no reason that I — well, what exactly? Well, no reason that I couldn’t be the man about town that, in 1980, I was suddenly qualified to be. Six months in college, 12 months of working (though not writing) at a newspaper and 12 of playing music in bars had exposed me to a lot of new ideas, new experiences and most important, new possibilities. My nerve endings had grown for miles in all sorts of new directions. And they were tingling.

In particular, after years of feeling invisible around women, I was suddenly an object of interest to them. This goes to your head, etc. At the time I was living with a woman whom I’d seduced unfairly and in error, proceeding on looks alone. And as the possibilities multiplied, the home fires dwindled. By the days of the DTL, the handwriting was on that wall too. Maybe it was just my stage of life and had nothing to do with the nightclub, but it’s also true that there is nothing like an exciting scene to excite a person.

I remember one time when after a particularly fun night at the club, several of us were standing around speculating about getting more DTL bookings. Will Jackson’s name was mentioned; the woman I was with said, “Well, Will Jackson isn’t God!” And I looked up and there was Will looking back at me. No, he wasn’t God, but we had common interests, and suddenly I realized that the woman and I had one less of those.

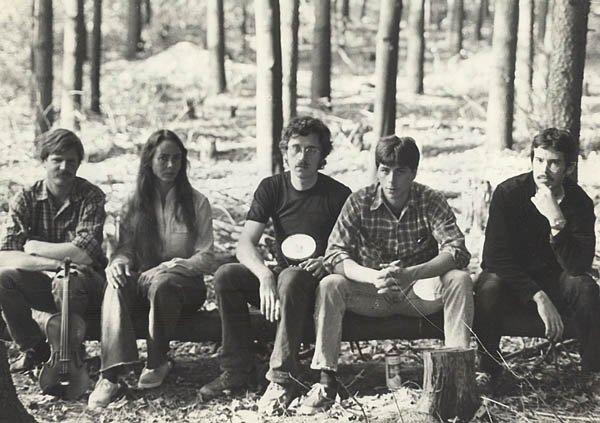

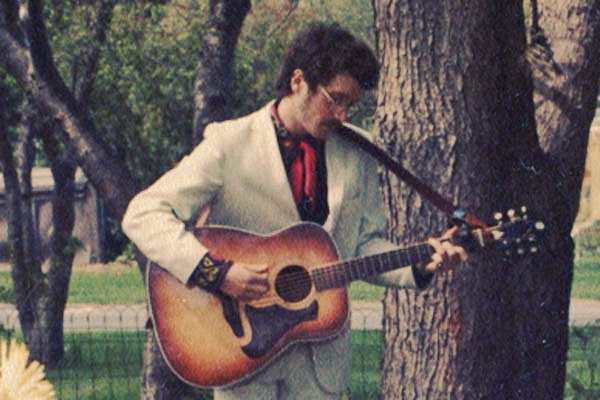

The original Fashion Jungle posing for a self-timer publicity shot in the Hubleys’ basement. From left: Doug Hubley, Ken Reynolds, Jim Sullivan, Mike Piscopo. Hubley Archives.

(Interestingly enough, on another night at the DTL, I spied among the dancers a dark-haired girl wearing striped coveralls and a keen perceptivity. “That’s someone I’d like to get to know,” I thought to myself. Eventually I did, in a class at USM — philosophy of art, of all things — and Gretchen Schaefer and I have been together ever since.)

The ironic thing was that while the DTL, in a sense, made the Fashion Jungle, the FJ never played there (at least under that name. In fact, singer Chris Hanson was absent for the Mirrors’ “country night” gig, making that an FJ gig in personnel if not in repertoire.) The FJ came into being in spring 1981, but by then the DTL was long gone, having collapsed in late 1980 during a rollicking stretch of time whose other events included my leaving my lover, Reagan getting elected president and John Lennon getting shot.

Well, there was nothing to be done about Reagan and Lennon. But Portland learned its lesson from the DTL, and thenceforth there was nearly always at least one joint where you could you catch music brainier than the usual club fare. For me it wasn’t so much about learning lessons: I was never a DTL insider, but the DTL got inside me. I simply walked in there as one person, and walked out as another.

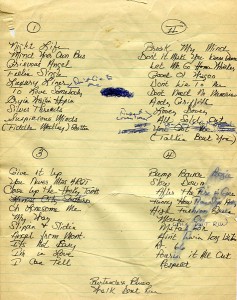

Here are the remaining FJ demos from the beloved Reel 96. Personnel: Doug Hubley, Mike Piscopo, Ken Reynolds (drums on all tracks), Jim Sullivan. Recorded on the Sony TC540 in Ben and Hattie Hubley’s basement, South Portland, Maine, summer 1981.

- Censorship (Sullivan) Another social commentary by Jim, who also plays the sax while I sing lead and play guitar. Jim was learning sax all the while the Mirrors were beating our way from country bar to country bar in Maine; I’d love to hear Jim’s thoughts on what influence his new instrument had on his interest in going the FJ way. Mike, bass.

- Shortwave Radio (Hubley) I started writing the lyrics in an art history class at USM, and finished the song up over a gin gimlet in my sister’s living room on a sunny summer evening, Bob Newhart on the TV, volume muted. This stayed in the repertoire for more than 20 years, from the FJ through the Howling Turbines. Mike, bass; Jim, organ.

- She Lives Downstairs (Hubley-Piscopo-Reynolds-Sullivan) Like “Dumb Models,” this was a product of the short-lived “song-per-week” phase when everyone tried to bring in at least a musical fragment that we could work with. This is based around a typically earnest KR lyric. Note the nods to “Gloria” and “Gimme Some Loving.” Doug, lead vocal, lead guitar. Mike, backing vocal, rhythm guitar (we were both playing Gretsches, hence the groovy sound). Jim, backing vocal, bass.

- Keep on Smiling (Hubley) The push for original material was so insistent that I revived this song created in 1973, when I was mad at one of my friends. These lyrics are melodramatic but the overall sense of angst still works. The big anthemic ending turned into something of an FJ characteristic. Doug, Rickenbacker 12-string, vocal. Mike, backing vocal, bass. Jim, backing vocal, organ.

- Nothing Works (Hubley) John Rolfe and I contrived a setting for my rather silly, but nihilistic in a still-pertinent way, lyrics in 1973. But for the FJ, wishing no encumbrances from the past, I devised a new tune. Doug, Rickenbacker 12-string, vocal. Mike, backing vocal, bass. Jim, backing vocal, organ.

“Censorship” copyright © 1981 by James Sullivan. “Shortwave Radio” copyright © 1981 by Douglas L. Hubley. “She Lives Downstairs” copyright © 2011 by Douglas Hubley, Michael Piscopo, Kenneth Reynolds and James Sullivan. “Keep on Smiling” and “Nothing Works” copyright © 2010 by Douglas Hubley. All rights reserved.

* In this sense, referring less to the major label-supported “safe” responses to punk and more to the wild embrace of all kinds of music, from reggae to ’60s pop, that seemed to retain some kind of integrity.

Text copyright © 2012 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.