From the Vault: Memos and Demos

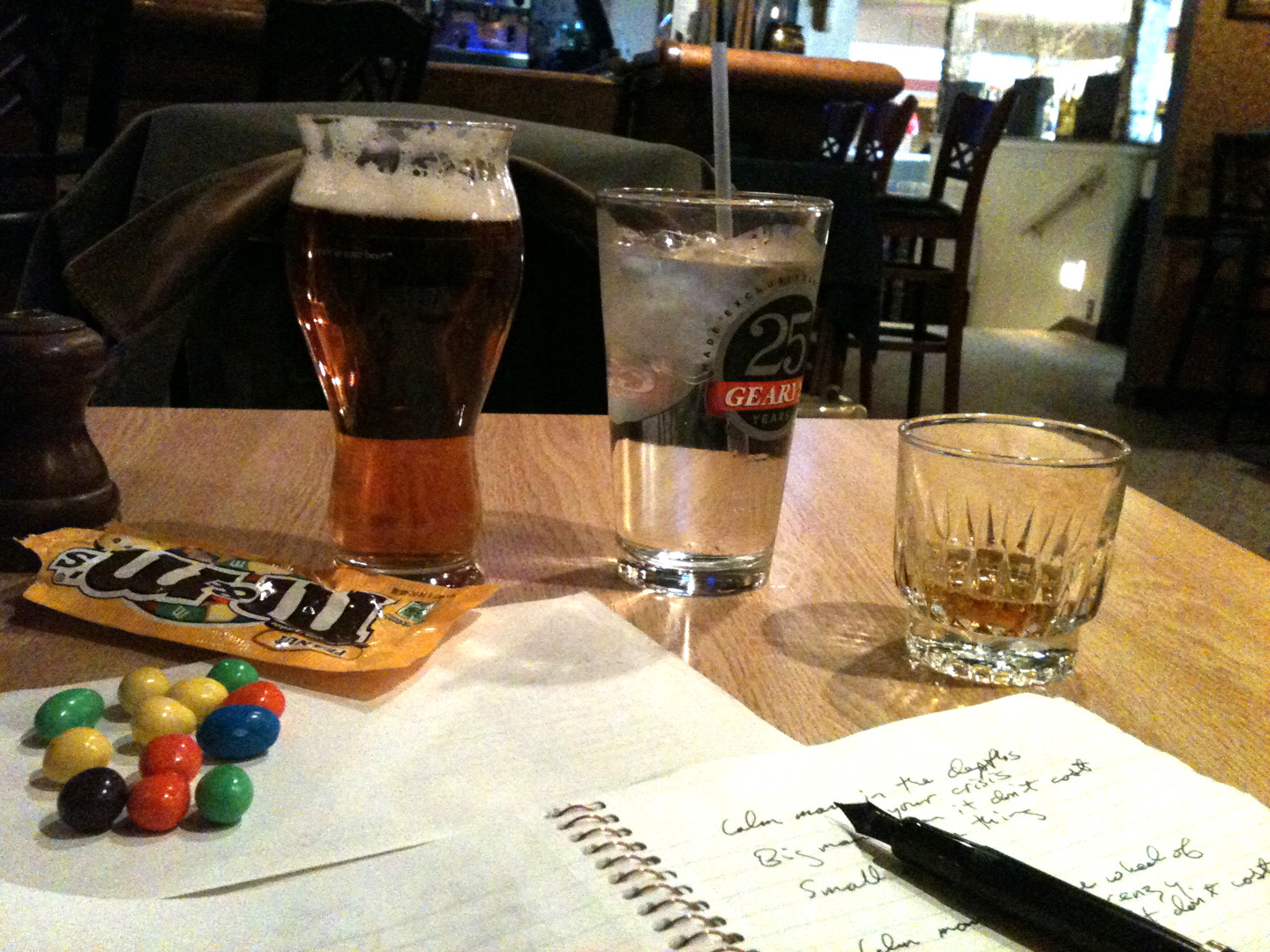

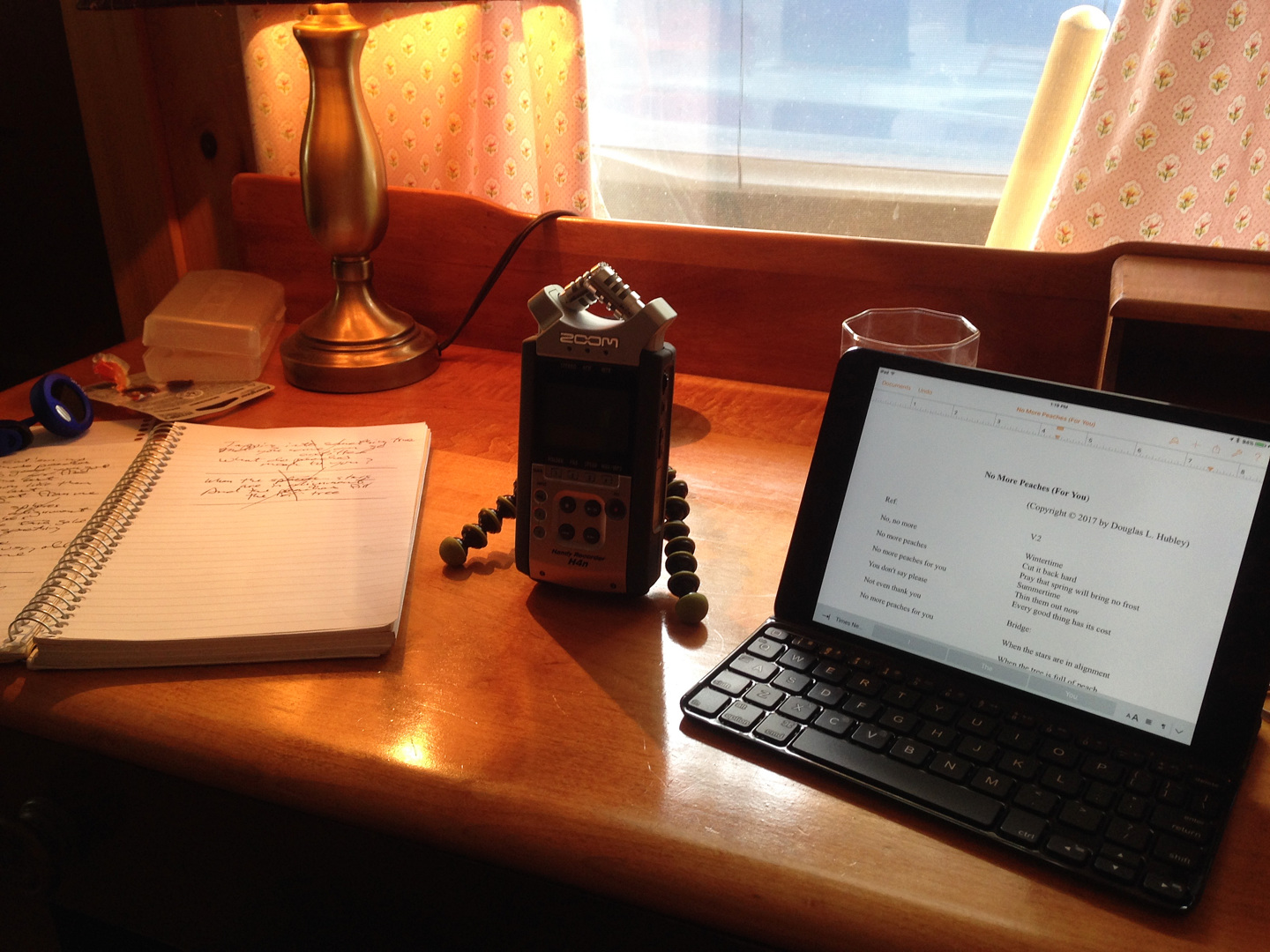

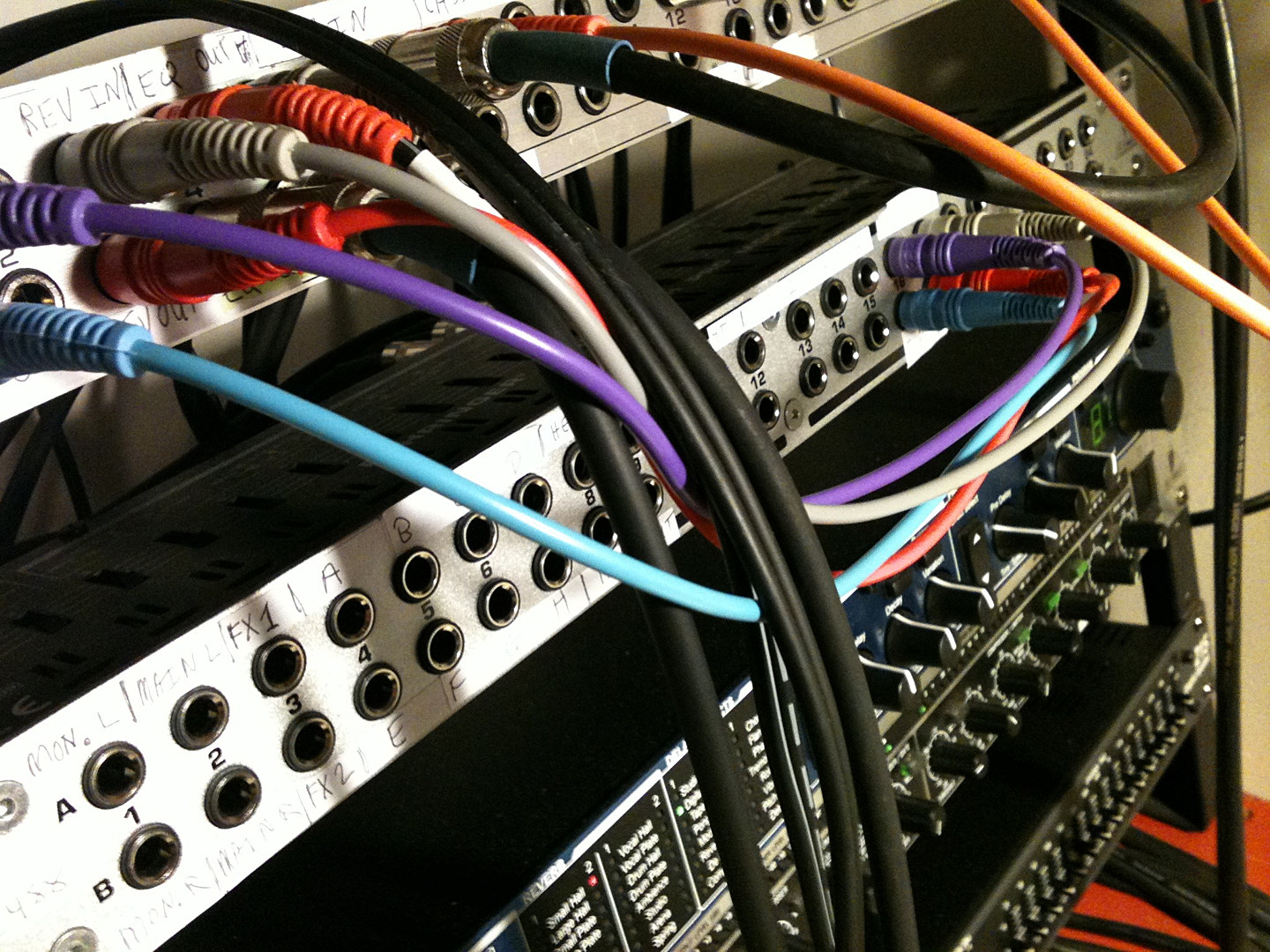

The setup for a songwriting session at the Maine Idyll motor court in Freeport, Maine, October 2017. Hubley Archives.

Skip the wordy blabbington and hightail it directly to the Bandcamp album!

Sometime in the fall

of 1972 I wrote a song called “Waiting.” I was 18 and the lyrics of “Waiting” were correspondingly melodramatic, but the music had possibilities in a Jefferson Airplane kind of way. In any case, at the time I thought it was just fine.

My band at the time was Airmobile (named for a song by Tim Hardin and Artie Butler — um, and Chuck Berry), and my bandmates were singer-guitarist John Rolfe, bassist Tom Berg and drummer Eddie Greco. We rehearsed in Eddie’s garage in Cape Elizabeth and played a few dates at the South Portland Rec Center and similar milestone-on-the-road-to-fame engagements.

I wanted the band to learn “Waiting,” and so in December I recorded a demo in my parents’ basement. Wow! Awful! There’s some decent lead guitar (Neil Young and Jorma Kaukonen much? etc.), but limited exposure is the only way to survive this recording — distorted, shrill, badly sung and drenched with reverb.

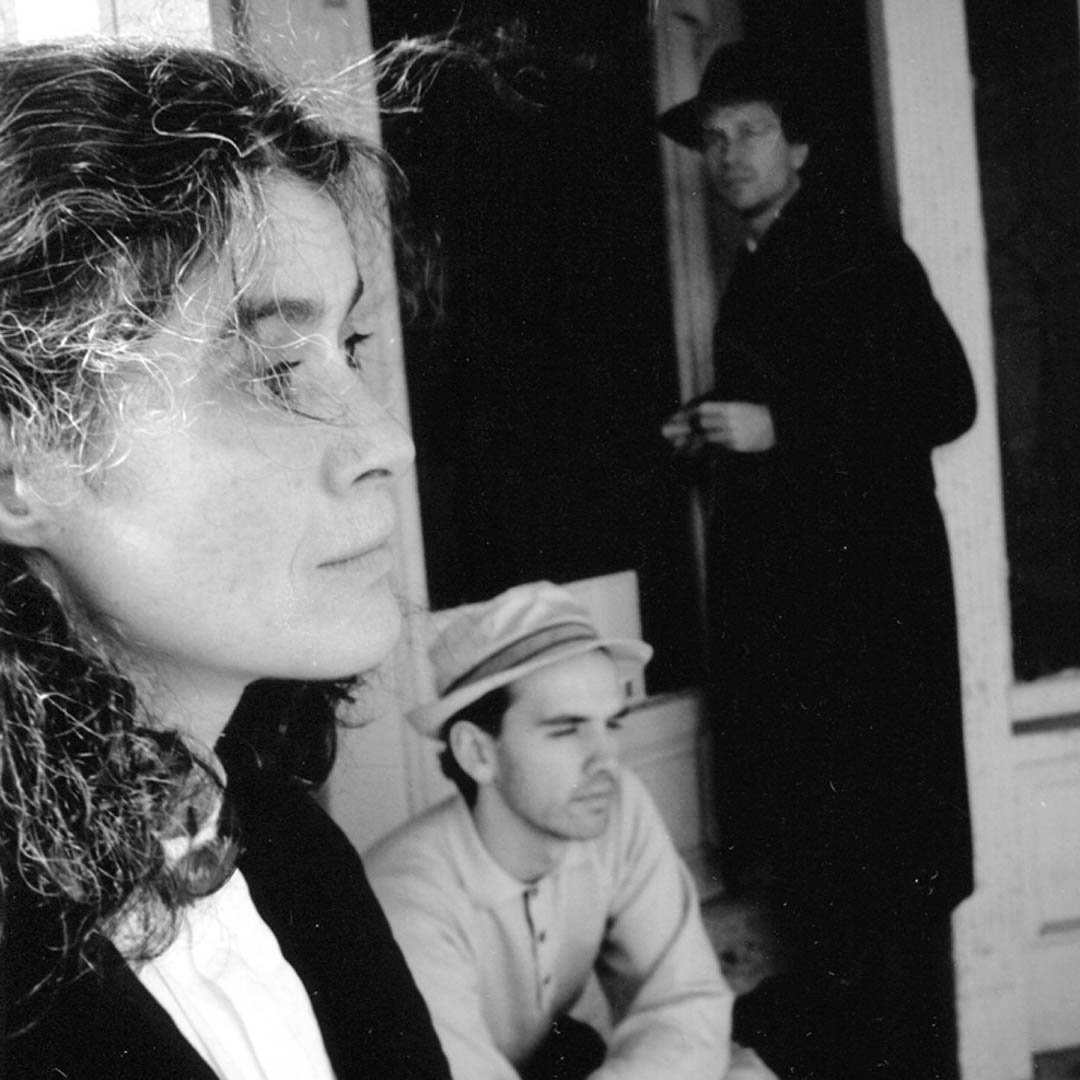

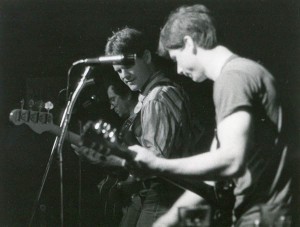

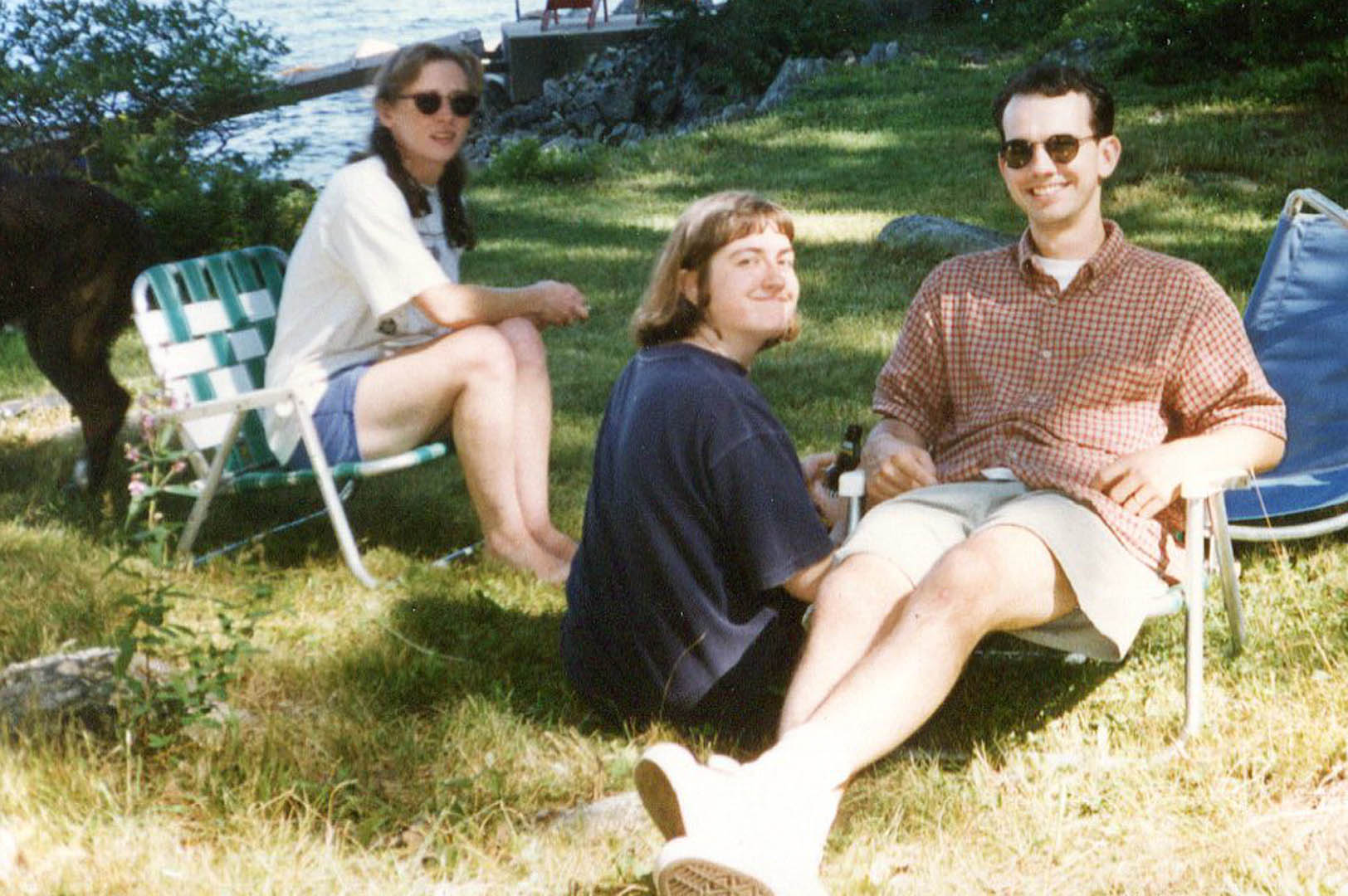

Remnants of an Airmobile, together again for the last time at a party at John Rolfe’s apartment in the 1980s. From left, Ed Greco, Doug Hubley, John Rolfe. Jeff Stanton photo.

We never did add “Waiting” to our repertoire, because the song is no root beer float and the demo sure doesn’t help it. But it does have the dubious distinction of being the first demo labeled as such in The Tape Catalog, the contents list of all my hundreds of homemade recordings.

As a demo, “Waiting” has scant company in the reel-to-reel section of the catalog, maybe four or five songs. (As a bad recording of a cringeworthy piece of music, however, it has all kinds of company.) There wasn’t much need for demos: I’ve never been a prolific songwriter, for one thing. And anyway, in the days when I was playing with electric bands, it was just as easy to teach my occasional creations to the group at rehearsal.

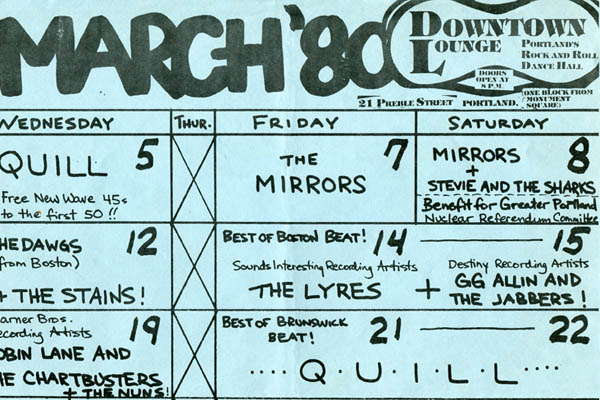

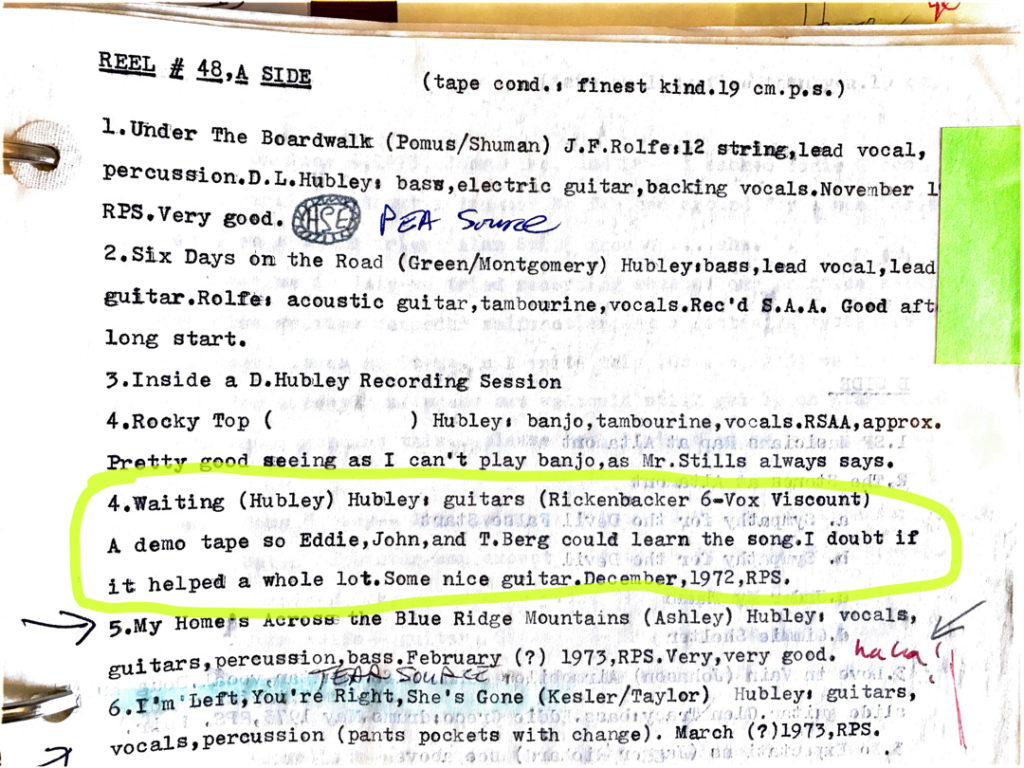

“Waiting” in the Tape Catalog. The weird “HSE” emblem is the Hubley Seal of Approval, reserved for tracks that I wouldn’t have been embarrassed to play for company in the mid-1970s. “PEA Source” and “Tear Source” indicate that these cuts appeared on the “Forty Years of a Basement” compilations Phoney English Accent and Tear in Every Eye, respectively. The Post-It was telling me there was usable material on this tape. The “ha, ha” — well, ha, ha.

For many years, when I did rise to the level of demo’ing a song, that may have been more about my state of mind than anything else. Hence the 1983 version of “Nothing to Say” (below) that, for me and the Gretsch Anniversary Model, is a sustained howl as much as it is a teaching tool.

A four-track recorder that I obtained in 1994 encouraged me to develop more of a demo habit. It was the first recorder I’d had since 1987 that enabled me to overdub and, better yet, no tedious-but-perilous bouncing was needed to layer up three or four tracks, in contrast to the Sony reel-to-reel two-track I’d used for so long. (Bouncing is the technique of mixing multiple recorded tracks onto a blank track so you can reuse the first tracks for new parts. For me in the 1970s, this involved mixing the two Sony tracks onto a cassette recorder and then recording parts back onto the Sony alongside that mixdown.)

Suddenly I was back to building arrangements on tape, and I liked it as much as ever.

The band at that time was the Boarders, featuring Gretchen Schaefer, my partner then and now, on bass and Jonathan Nichols-Pethick on drums. In contrast to its covers-heavy predecessor outfit, the Cowlix, this trio developed a fair amount of originals and therefore had more use for demos. I had a few new or re-conceived songs, and Jon had a couple others that I interfered with — er, contributed to — with the four-track coming in handy.

Like demos often do, these reveal facets or details of the songs that got lost along the way, and it’s fun to compare what stayed and what sloughed off. And then there are memos: scratch recordings, often fragmentary, that those of us who can’t read or write music make to remember important bits, like melodies.

In the musical world

there is nothing special about demos and memos, and I’m riding in a commuter van writing this and trying to figure out how such recordings relate to my fixation on material objects, notably documents in whatever medium, and their role as anchors of memory.

Such recordings are not the keys to total recall, but most of the demos presented here do retain at least a vestige of their making, if only the glow from the metal-shaded lamp I use in the basement. Better than no memories at all.

There was a little outbreak of demo fever in the early 1980s, as Bruce Springsteen chose to issue his Nebraska material in the form of the original demos rather than as produced versions with the E Street Band; and Peter Townshend released Scoop, a demo compilation of songs first released (or not) by the Who. These raised my demo consciousness a bit, which probably explains the “Nothing to Say” recording.

But ultimately, for me there are thin lines or no lines at all dividing memos, demos and performances, especially if you view, as I do, all recordings of a song (or of all songs) as threads in a common fabric whose variations all tint and reflect each other’s light.

Phenomena like hit singles or TV performances that change a viewer’s life (does that still happen?) can instill the idea of songs having “definitive” versions. And so they may be — in broad cultural terms. (We’ve all got ’em, although I may be distinctive in my affection for the wrong note Chris Hillman plays for half a bar in “Spanish Harlem Incident” on Mr. Tambourine Man. On the basis of no evidence, I’m convinced he needed a drag off a cigarette.)

Patch bays in the basement enable me to “associate many things with many things,” as Bunny Watson said. Hubley Archives.

But from a narrower musical perspective, “definitive version” is almost a laughable idea. (And of course there are also laughable versions that are definitive in their own ways, if only as examples of what not to do. Welcome to my musical catalog.)

Every performance of a song listens to the one that came before and sings to the one that follows. It’s trite and not quite correct to say, “It’s all one version,” but all the performances of a song certainly do constitute one conversation about at least that one topic and probably more.

Which may be one reason that the more interesting professional musicians can sell their hits night after night.

Here’s the real difference, I guess: Unless you’re super-attuned to the stewardship of your public persona, the monetizing of every sequin on your character, etc., what distinguishes memos and demos is that they’re not created for an audience. And when they are heard outside your immediate circle, it’s more like being overheard, with all the accompanying qualities of authenticity, honesty, etc.

So, for your eavesdropping pleasure, here’s an assortment of demos and memos from a 30-year period, coupled with fully realized performances of the songs.

Song Notes

‘The Other Me’

Day for Night: Dirges had constituted most of my output after I resumed songwriting, in 2010, after a 12-year layoff. So when I started this song in 2016, it was time for something upbeat. “The Other Me” is still wordy, bleak and overly self-referential, but it has a good beat and you can dance to it.

I got most of the lyrics written in the bar of the Samoset Resort, in Rockport, Maine, while Gretchen Schaefer (my partner in life and music) was showing mosaics at a craft fair at the resort. But the tune, especially the bridge, was problematic and I had to hammer away at it for quite a while.

“The Other Me” was also a bear to learn, necessitating a few changes of key and arrangement before we found something that we liked. And this is it, recorded on Aug. 5, 2018, at Quill Books & Beverage in Westbrook, Maine. Hear it on Bandcamp (and click through on the audio player title to purchase):

Demo: Recorded on Oct. 2, 2016, in the computer room, this memo includes one of a few bridge melodies that I tried and discarded before arriving at something usable later in the month. Hear (and buy) it on Bandcamp:

(“The Other Me” copyright © 2017 by Doug Hubley. All rights reserved.)

‘Dumb Models’

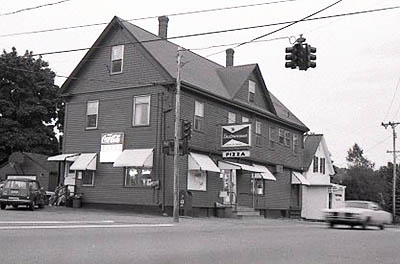

The Corner, summer 1981: It’s Patty Ann’s Superette in South Portland and the original Fashion Jungle is posing casually just prior to a party performance at Sebago Lake. Also starring my beloved 1973 VW Squareback, into which I could pack nearly all the FJ gear except the drums. Photo by Jeff Stanton.

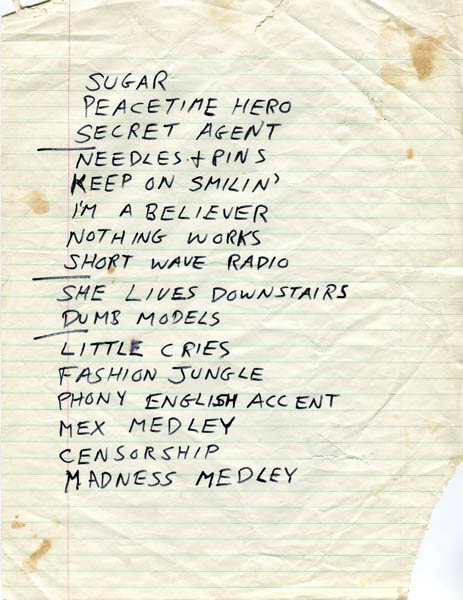

The Fashion Jungle: This isn’t a demo, it’s a memo. When my band the Mirrors became the Fashion Jungle, a rule was that everyone had to bring in at least a fragment of original music each week. Here’s a result of that discipline: the lyrics are by Ken Reynolds, edited by me; the opening guitar riff was Mike Piscopo’s; and with the fourth member of the band being Jim Sullivan, we collectively put the whole thing together in June 1981. We made this seldom-heard recording early in the song’s life so as not to forget it during our vacations.

A billy nice guy? Never mind. Anyway, we later added chorus vocals and a “bah-bah-bah” coda, very 1968. Doug Hubley, 12-string guitar and vocal; Mike Piscopo, 6-string guitar (lead guitar in the refrain); Ken Reynolds, drums; Jim Sullivan, bass. Recorded on the Sony two-track in the Hubleys’ basement (and I don’t know where that tone at the end came from). Bandcamp:

The next Fashion Jungle: And here we are more than a year later and with the next iteration of the FJ: Jim and Mike have moved on, and Steve Chapman has joined on bass. The performance was recorded at Jim’s Neighborhood Cafe, Danforth Street, on Oct. 6, 1982. I miss the growl of Mike’s Gretsch guitar, but Steve provides his own kind of roar.

(“Dumb Models” copyright © 2011 by Douglas Hubley, Michael Piscopo, Kenneth Reynolds and James Sullivan. All rights reserved. )

‘Watching You Go’

Demo: The immediate impetus for this song seems a little immature — the death of my cat Harry. But I did realize that this was a topic to be addressed at a more sophisticated level, and fortunately I was able to generalize the lyrics somewhat beyond “my kitty died.” (He was a pretty cool cat, though.)

I suppose I was looking ahead to a period such as this, in which I’ve lost my mother, father and a good friend in the space of two years. But I can’t say I’ve wanted to sing this song much lately.

Recorded in the basement in autumn 1995 on the Tascam 4-track. Tracks: acoustic guitar, voice, and percussion consisting of my foot and change being jingled in my pockets. Bandcamp:

The Boarders: On a windy and rainy Jan. 19, 1996, we performed live on the University of Southern Maine radio show “Local Motives.” It was almost a fun experience, except for an inept audio engineer who suppressed Gretchen’s bass almost to the vanishing point on many songs (it was recoverable on this number) and slathered digital reverb and delay all over us (at the beginning of this track, you can hear the doofus searching for the correct tempo on the delay). Jon Nichols-Pethick, drums. Bandcamp:

(“Watching You Go” copyright © 1996 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.)

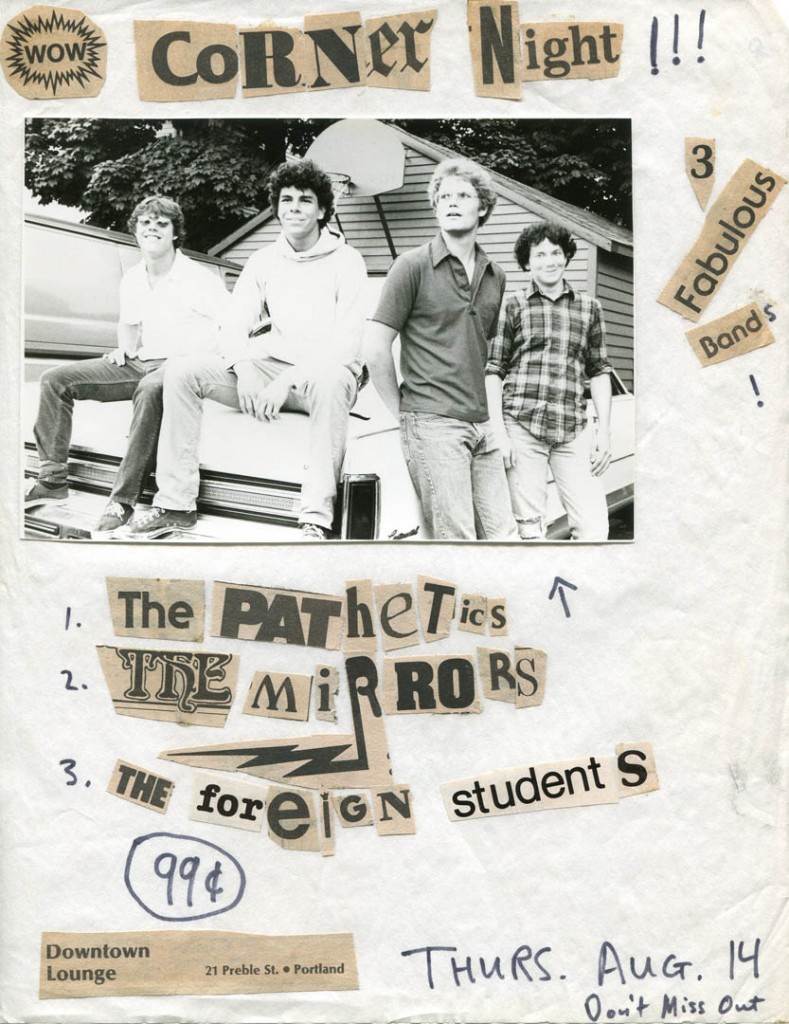

‘Corner Night’

Gretchen Schaefer, Dan Knight and Jeff Stanton at Frosty’s doughnut shop, Brunswick, July 1985. We were in Brunswick to see a concert at Bowdoin College by Richard Thompson, who was wearing a pink suit that clashed quite splendidly with his red hair. Having interviewed him for a Press Herald advance a few weeks earlier, I felt entitled to corner Thompson backstage and force an FJ tape on him. Hubley Archives.

Demo: This song is an attempt to come to grips with the fleeting nature of local rock bands and local fame, or at least recognition, of the kind the Fashion Jungle briefly enjoyed in the 1980s. Corner Night itself was actually a show, a triple bill that the Mirrors / Fashion Jungle, John Rolfe’s Foreign Students and Gary Piscopo’s Pathetix presented in 1980 and ’81. All three bands had ties to Patty Ann’s Superette, aka The Corner, in South Portland.

I wrote the words in 1981 after Mike Piscopo and Jim Sullivan left the Fashion Jungle, and finished the song after Steve Chapman and Kathren Torraca left in 1984. The song holds up — one of my better melodies, although the lyrics are very insidery. Yes, the Elvis Costello imitation is embarrassing, and there’s also some debt to Ray Davies’ “Waterloo Sunset.” This demo was recorded on the two-track Sony in my parents’ basement in 1985 for the Dan Knight lineup of the FJ. Bandcamp:

The Fashion Jungle: And here’s the Knight-era FJ performing the song at Geno’s, in Portland, on July 27, 1985. We were opening for Judy’s Tiny Head, and taping the show off their sound board helped some with recording quality. What is an interesting and intricate arrangement on the demo turns into a busyness for its own sake here, but kudos to bassist Dan and drummer Ken Reynolds for taking all those twists and turns so tightly.

(“Corner Night” copyright © 2010 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.)

‘I Never Drink Alone’

When we perform, I like to joke that this is the most depressing song I’ve ever written, most depressing you’ll ever hear, etc. I say it to be funny but also to show some self-awareness, because this really is a downer.

Well, that’s life: This, like “Watching You Go,” is an attempt to anticipate or envision or reconcile myself to — or try to inoculate myself against — the potentially barren landscape of old age. I wrote it in 2012, during which year my sisters and Gretchen and I were starting preparations for moving Ben and Hattie Hubley, who were in their early 90s, into a memory-care facility.

Day for Night: Recorded in a living room rehearsal on Nov. 27, 2016.

Memo: This is a hotel room recording made so I could remember the melody. (One wonders if there was any sort of decline in sales of music notation paper that was correlated with the advent of portable audio recorders.) I made the recording in the Sheraton Hotel in Portsmouth, N.H., on Feb. 23, 2012.

(“I Never Drink Alone” copyright © 2014 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.)

‘Tragedy’

Demo: The second original in the catalog from Jonathan Nichols-Pethick, drummer of the Boarders, who had previously contributed “All Over” to the Cowlix. He co-wrote this song with his wife, Nancy. I added a signature riff and a few lyrics, and heightened the S&M overtones a bit (or so I would like to believe).

Recorded in the basement in autumn 1995 on the Tascam 4-track. Tracks: acoustic guitars and voice.

The Boarders: And here’s the whole band playing it, recorded in rehearsal on Dec. 5, 1995. Dropped line: “You say, ‘I need another drink.'”

(“Tragedy” copyright © 1995 by Jonathan Nichols-Pethick, Nancy Nichols-Pethick and Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.)

Nancy, at center, and Jonathan Nichols-Pethick at their farewell party in July 1996. At left is Louise Philbrick. Hubley Archives.

‘Just a Word From You, Sir’

Howling Turbines: If you’re wondering, this number from 1997 is generally about my relationship with authority and specifically about Stalin, Leonard Cohen and God. So there.

Anyhoo, this is the first of two very different versions of a song (one of two) I wrote for the Howling Turbines. Here’s the original setting, which was an attempt to capitalize on what I perceived as our heavy-rock potential (I had bought a distortion pedal that changed my world). Performed by the Turbines in the basement in March 1998. Bandcamp:

Demo: I prefer the above version now, but at the time we didn’t feel it was working for us. This demo from April 11, 1999, captures my second setting of the song, which is more sophisticated than the original but ultimately reminded me of something Davy Jones should be singing. This is how the Turbines did it for a while, but it ultimately fell out of the repertoire.

(“Just a Word From You, Sir” copyright 2010 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.)

The Howling Turbines on a blistering hot day at the Free Street Taverna, Aug. 1, 1999: from left, drummer Ken Reynolds, bassist Gretchen Schaefer and me — guitarist and singer Doug Hubley. Photo by Jeff Stanton.

‘Dance’

Demo / The Boarders: Just to round things out, here’s a demo and a final version neatly packaged together. “Dance” started out with with the Fashion Jungle, my lyrics riding on a tune created collaboratively by Steve Chapman, Ken Reynolds and me. Six or seven years later, casting about for material for the Boarders and feeling no more optimistic about the fate of the world, I rediscovered these lyrics, for which I created a new tune.

The first third is the demo that I made for Gretchen and Jonathan to learn it from; the remainder, cleverly spliced on through the cleverness of digital audio editing, is the Boarders playing the song on July 9, 1996, at Forest Avenue. The Boarders section is a copy of a copy that was made on a mastering deck with a wow-and-flutter problem, hence the wowing and fluttering.

(“Dance” (Boarders version) copyright © 2010 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.)

The Fashion Jungle: And here’s the original setting. Sounding very FJ at our most melodramatically disco-licious, this came off the sound board at the 1988 Maine Festival, recorded on a sultry August evening in Deering Oaks. That was a fine event despite my guitar-tuning issues. I rediscovered this recording while going through tapes for this CD set; most of the cuts on the tape were lost or damaged because of a bad connection, but this survived intact, albeit with drums taking up 80 percent of the soundscape.

(“Dance” (Fashion Jungle version) copyright © 2013 by Steven Chapman, Douglas Hubley and Kenneth Reynolds. All rights reserved.)

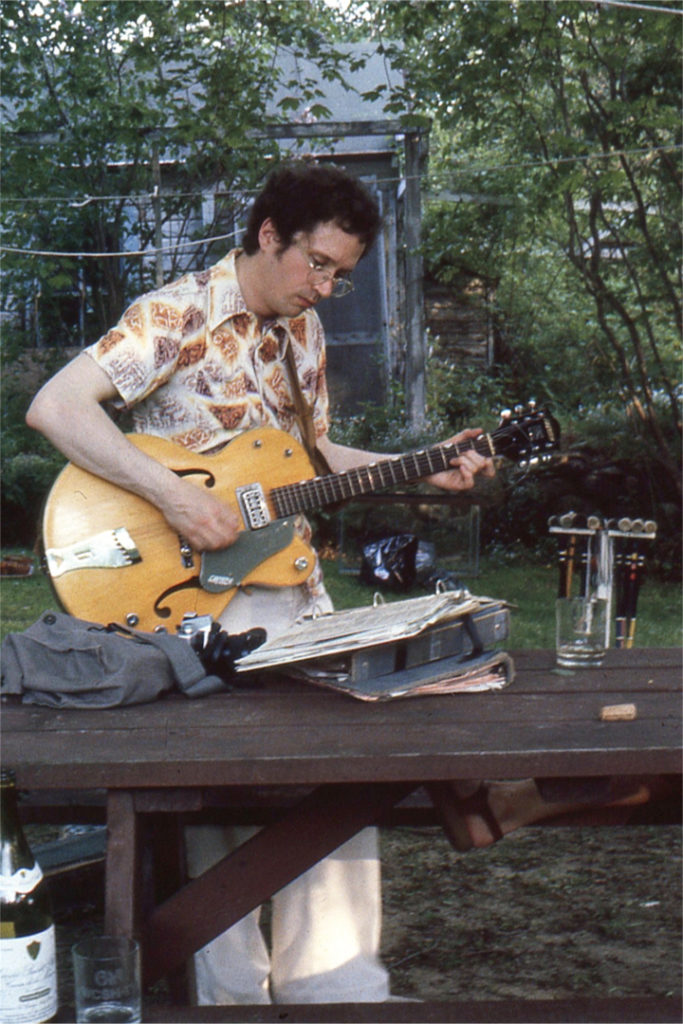

Doug plays the Gretsch Anniversary Model in Ben and Hattie’s back yard in summer 1983. Hubley Family photo.

‘Nothing to Say’

Demo: I remember stepping out onto Middle Street from the restaurant Carbur’s carrying the legal pad on which I had just finished these lyrics, which attempt to explore both my own shallowness and the big sellout of the punk-New Wave scene.

This one-track recording, made in September 1983 at Richland Street with the Gretsch Anniversary Model, was the demo that the FJ learned it from — another big anthem. Dropped line: “Now the room fills up with expectations while my blood drains away.”

The Fashion Jungle: The fully realized version by the Chapman-Torraca lineup of the Fashion Jungle, recorded in January 1984 at the Outlook, in Bethel. The lyrics sit better in this well-rehearsed performance, but the arrangement certainly has blossomed forth. The Anniversary Model returns for a solo. Steve Chapman, bass and backing vocals; DH, guitars and vocals; Ken Reynolds, drums and backing vocals; Kathren Torraca, keyboards. Remastered from the commercially released audiocassette Six Songs.

(“Nothing to Say” copyright © 1984 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.)

The Kathren Torraca-era Fashion Jungle in a publicity image taken in 1984 by Gretchen Schaefer. From left: Ken Reynolds, Kathren, Doug Hubley, Steve Chapman.

Notes From a Basement text copyright © 2012–2018 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.