Other Voices: The Fashion Jungle, 40 Years Later

- A complete listing of Notes from a Basement posts and Bandcamp albums relating to the Fashion Jungle appears at the end of this post.

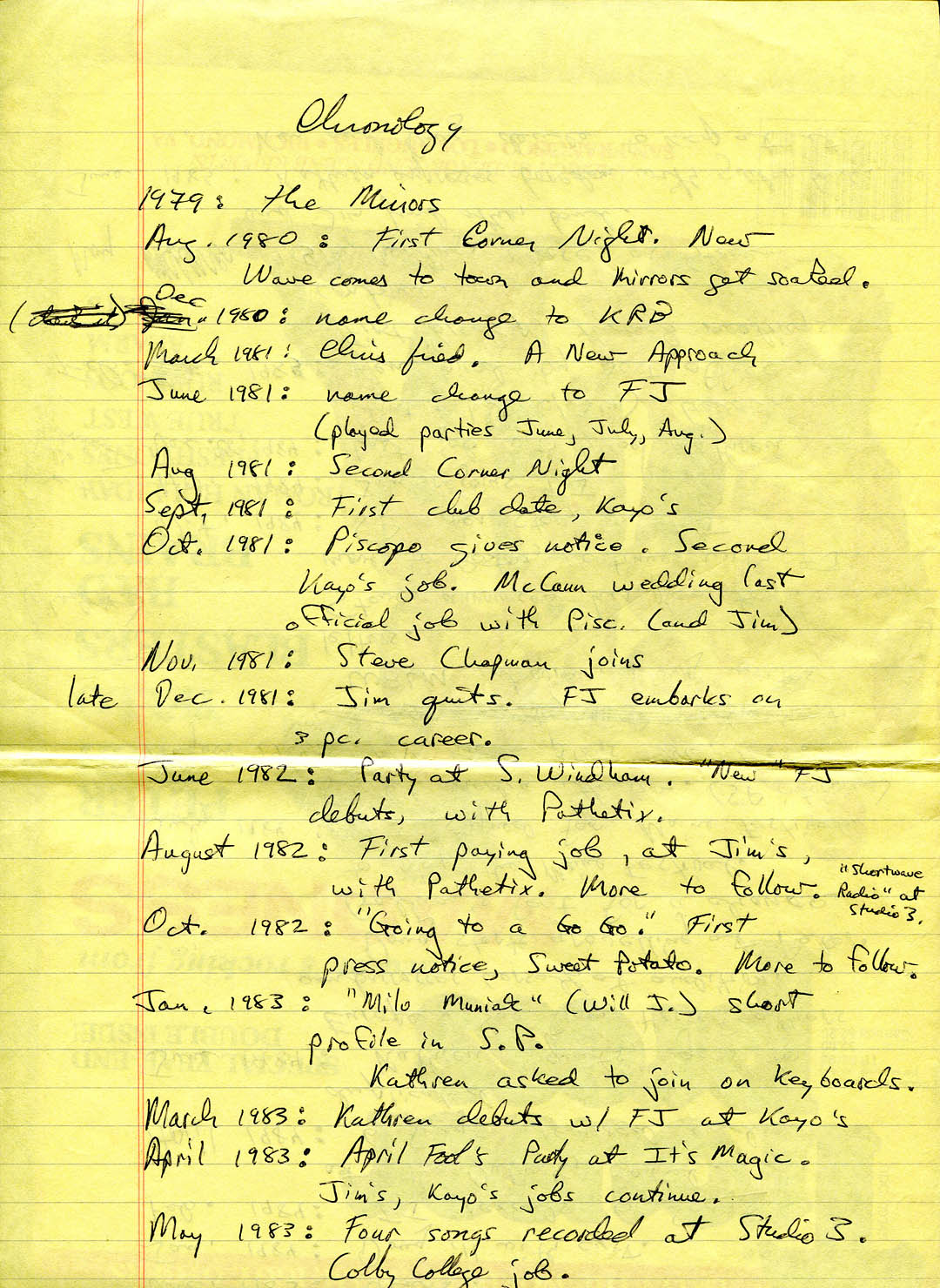

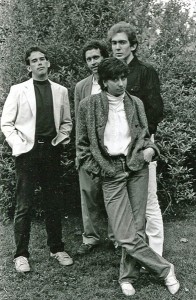

“It’s hard to believe it has been 40 years,” says Mike Piscopo — 40 years since the emergence of the Fashion Jungle, a rock band that he, Ken Reynolds, Jim Sullivan and I created.

Evolving over nine years from that original quartet to trio, quartet, quintet and trio again, the FJ remains an emotional landmark for many who were involved in it.

For me, the FJ was like graduation, as we sloughed off our covers-band identity as The Mirrors and focused, instead, on original songs rooted in personal experience and delivered with all the ardor we could muster.

“The FJ opened my eyes to the possibility that instead of just being a technician copying things, you could actually invent music with nothing limiting it but imagination,” says multi-instrumentalist and songwriter Jim Sullivan.

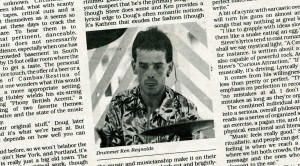

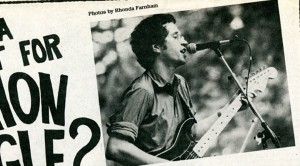

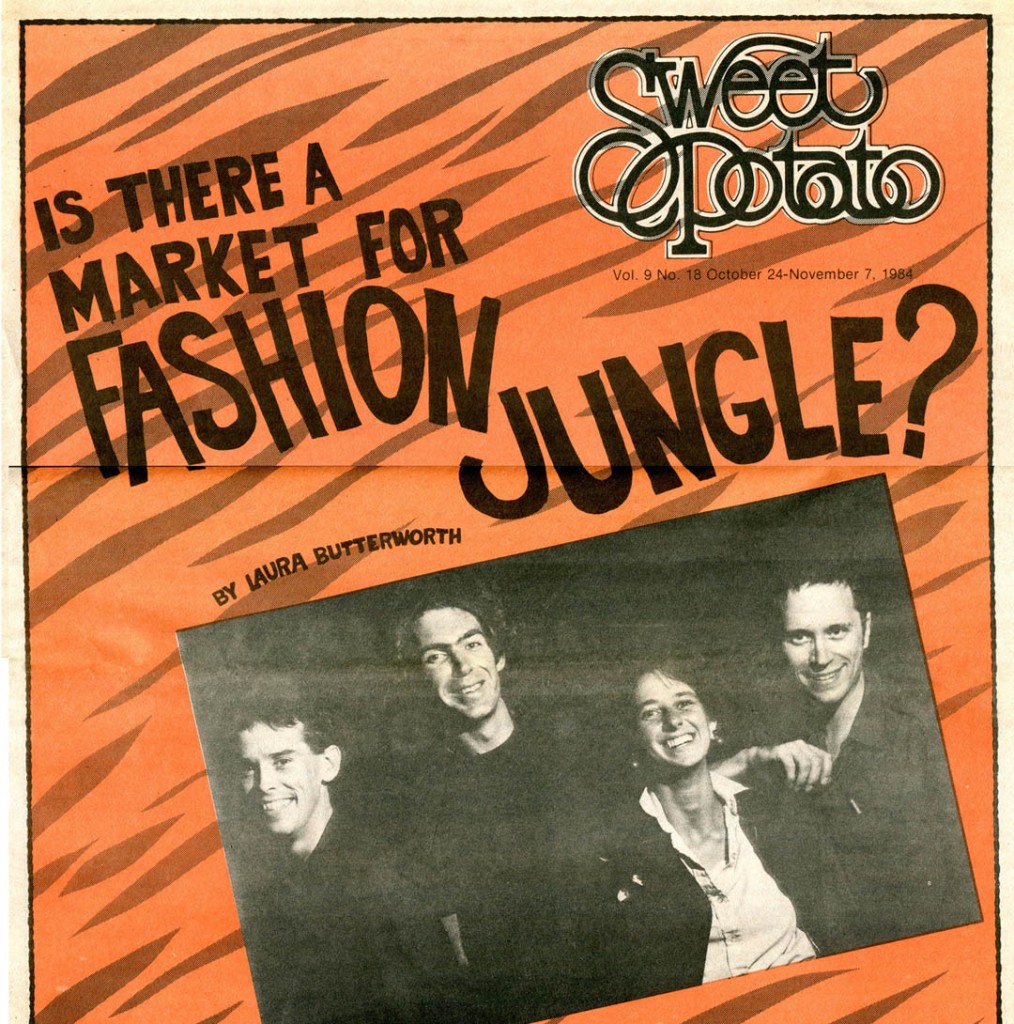

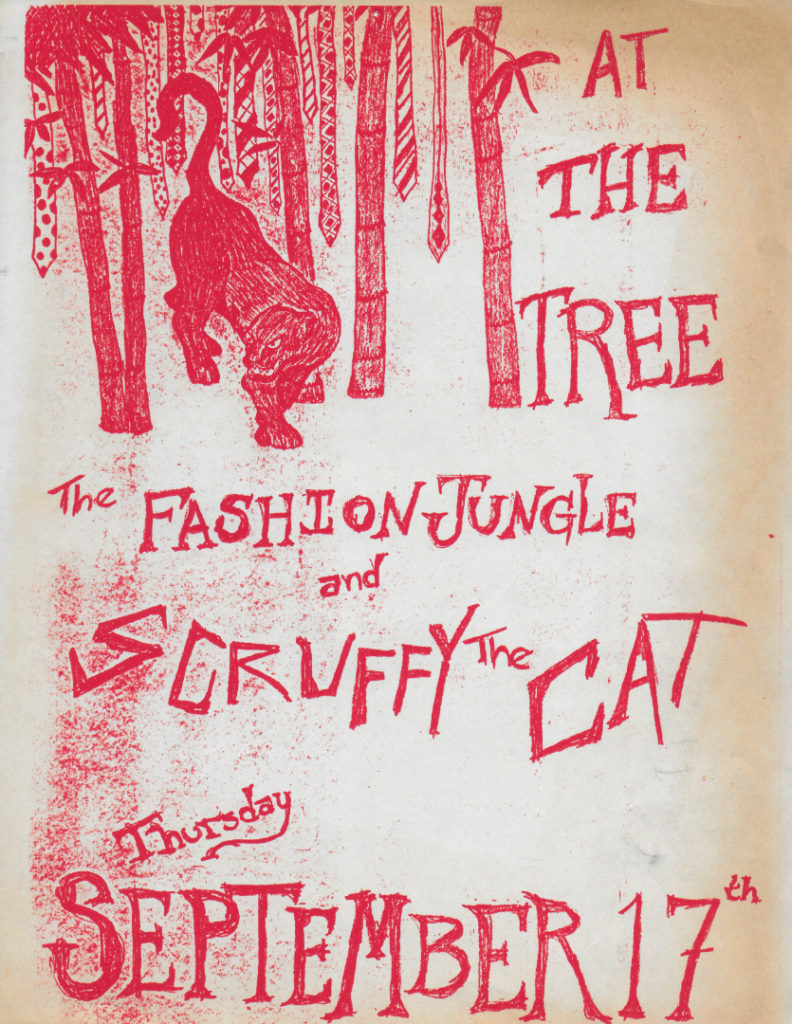

The 1980s rock press in Portland, Maine, were fans. The music magazine Sweet Potato put us on the cover three times and reviewed our shows. According to SP writers Seth Berner and Will Jackson, respectively, we were Maine’s “best ‘new wave’ songsters,” offering “[p]otent, provocative, inventive originals played with precision and intensity.”

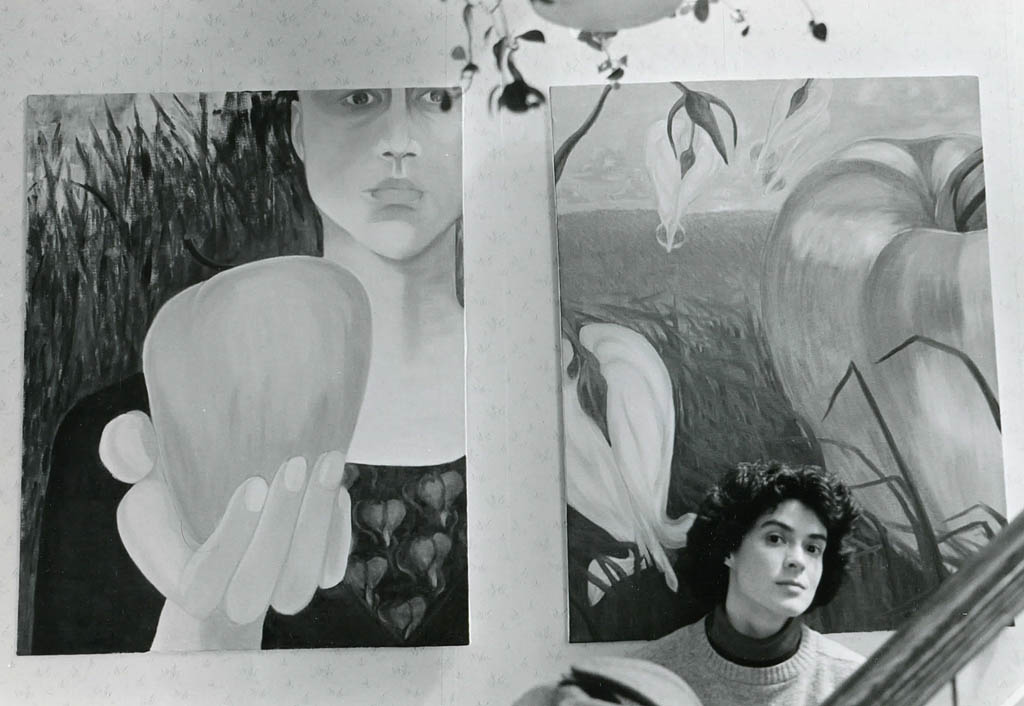

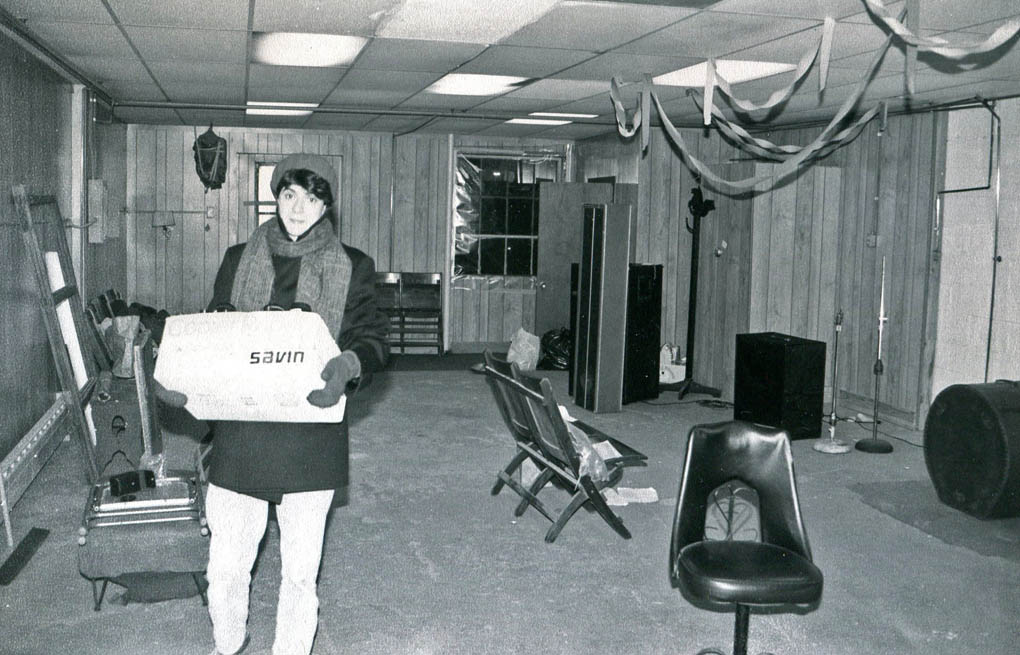

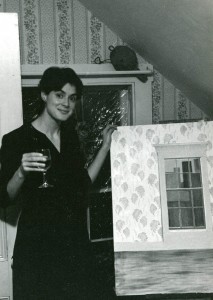

For me and for others involved with the band, the FJ years stand out as personally transformational. “I loved it,” says Gretchen Schaefer, who applied her talents in visual art to FJ projects and didn’t shy away from carrying amps. The excitement wasn’t totally about the music (or the fact that, even as the FJ was becoming a thing, she and I were building a relationship that’s still going strong). In some ways, the FJ was providing the soundtrack for myriad life changes within our circle.

In Gretchen’s case, she says, “I was taking myself more seriously as an artist at that time — it was the beginning of that for me. I finally was out of an extended adolescence and I felt like an adult with some agency in my life. I was doing things that young adults do, instead of just dubbing around as a student.”

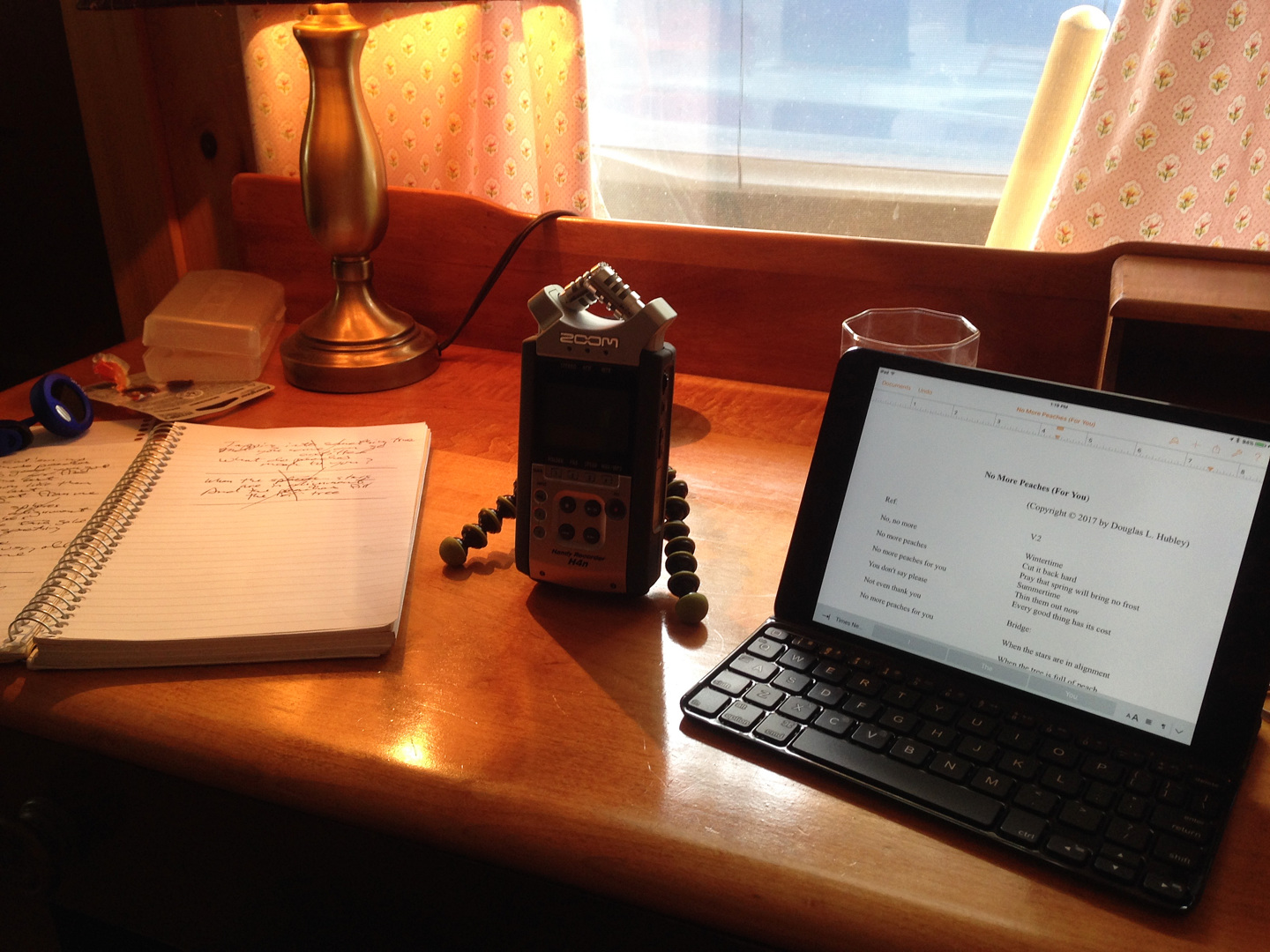

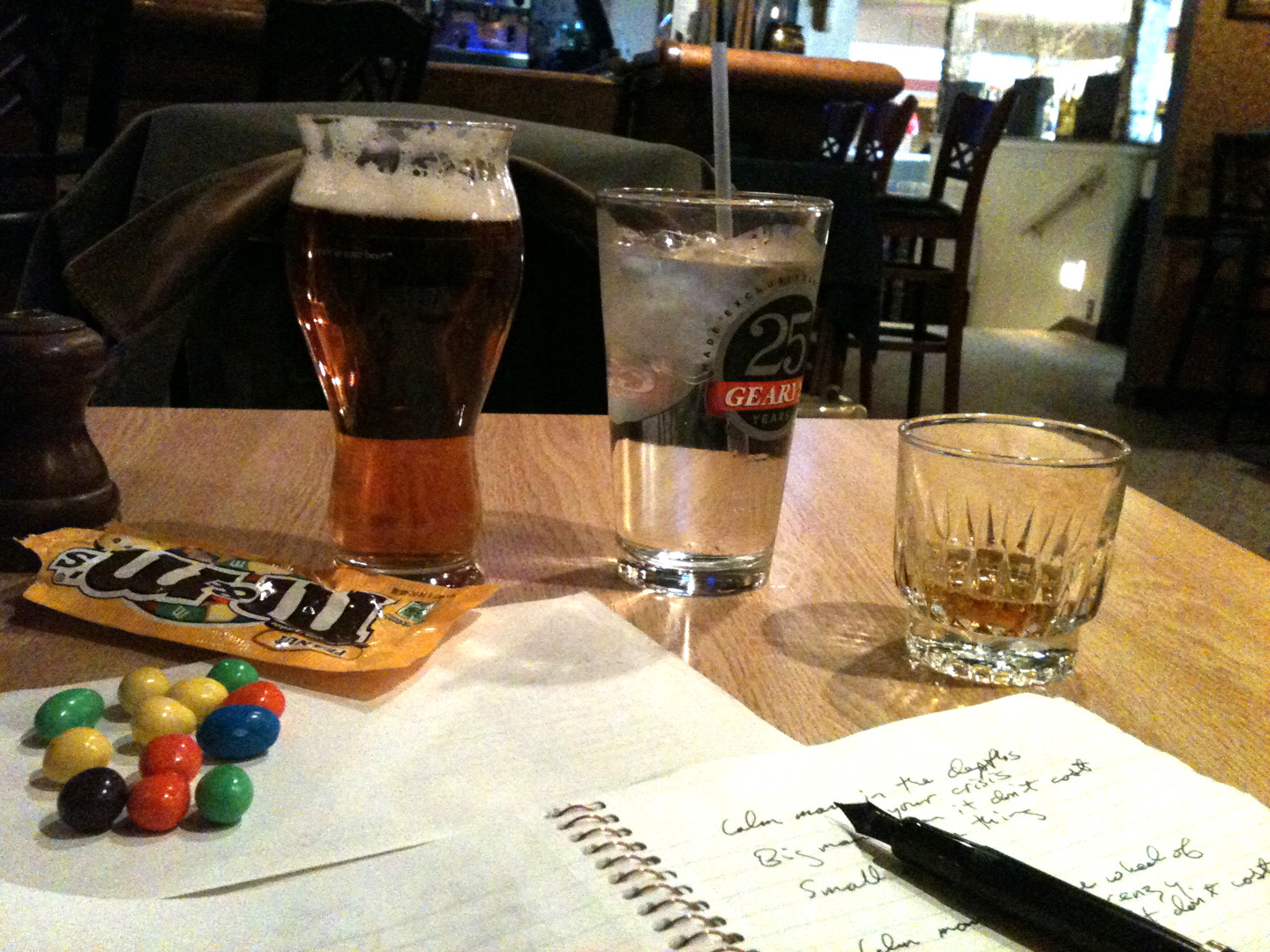

I realized early in 2021

that the 40th anniversary of the Fashion Jungle would arrive this summer, as Mike, Jim, Ken and I had settled on the FJ moniker in June 1981. And that anniversary is the perfect opportunity for a long-overdue departure from the solitary musings that typically constitute Notes from a Basement.

So, four decades after it all began, it’s a genuine pleasure to present a Fashion Jungle retrospective in the words of the people — other than me — who played in the band or supported the musicians through the occasional thick and the frequent episodes of thin. (Constitutionally unable to butt out, I do offer a few notes in italic type for clarity and continuity.) Read on to hear from:

- Ken Reynolds and Mike Piscopo, with whom I first played in the Curley Howard Band in the late 1970s;

- Jim Sullivan, who joined us in The Mirrors;

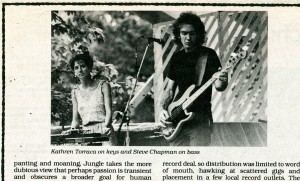

- Steve Chapman, who played with Ken and me in the band’s most enduring lineups;

- Kathren Torraca, whose youthful spark and keyboard work defined the best-known FJ lineup;

- Dan Knight, who helped fill a gap in the band’s eight years of being;

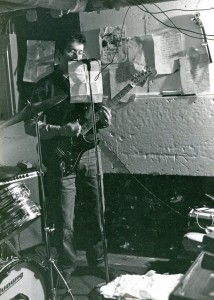

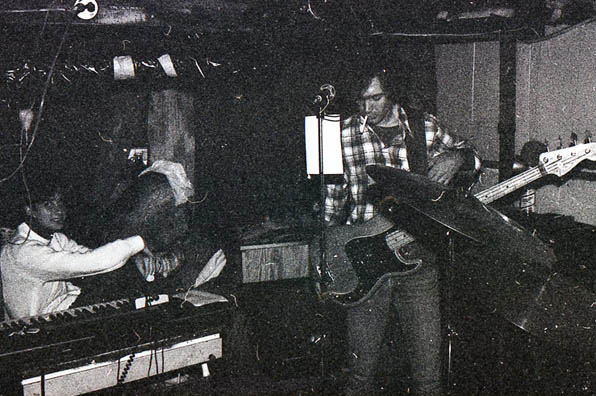

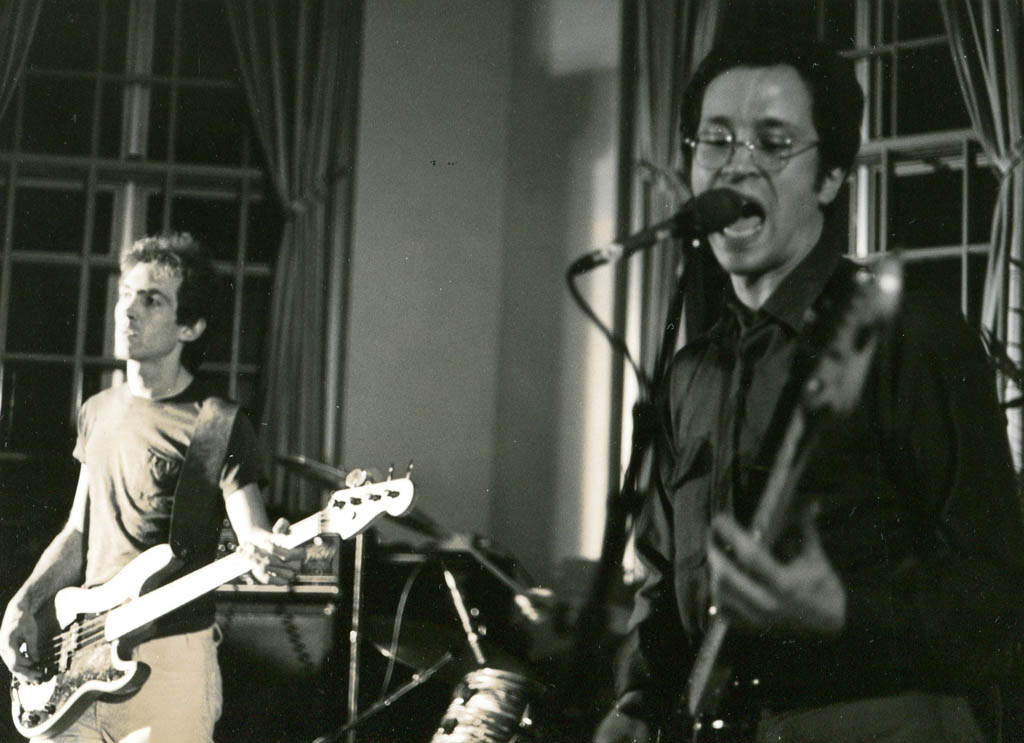

- and from Gretchen Schaefer and fellow roadie Jeff Stanton, whose photos have documented the adventures of the FJ and many of the bands that followed.

Ken Reynolds, take it away!

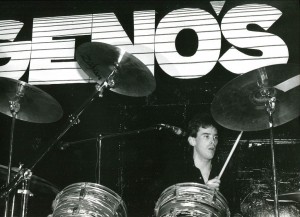

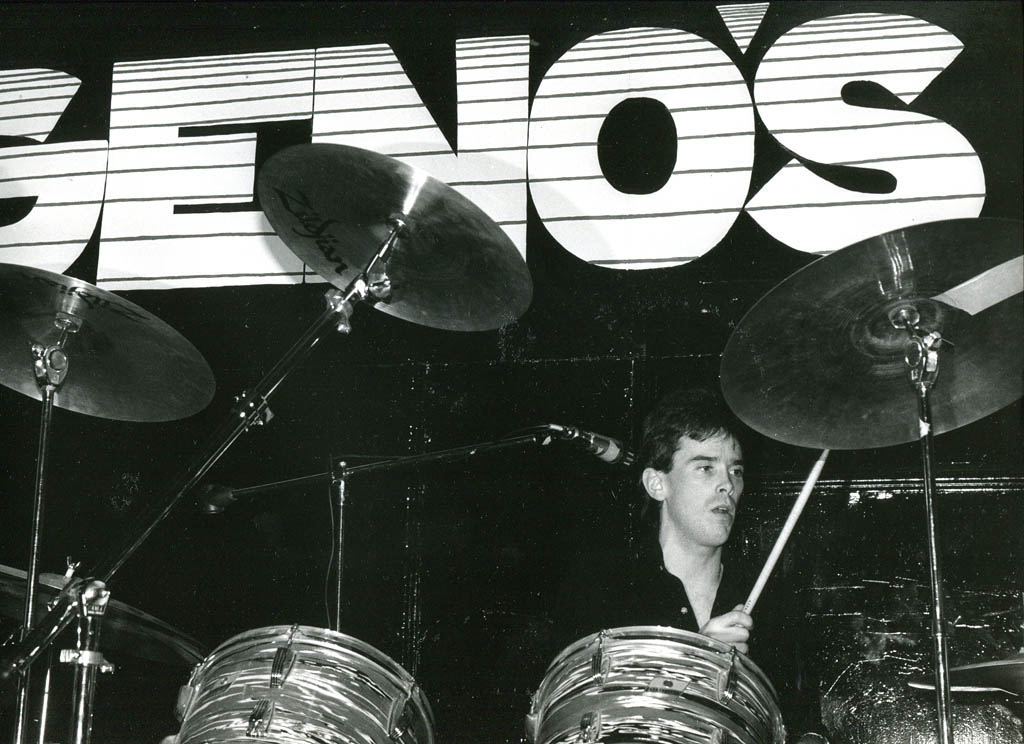

Ken Reynolds: Drums, vocals, lyrics

Curley Howard Band (1977–78) / The Mirrors (1979–81) / The Fashion Jungle (1981–89) / The Cowlix (1989–91) / Howling Turbines (1997–2004)

Ken and I met in 1975 as employees of the Jordan Marsh department store in South Portland, Maine. Our musical interests were quite disparate, but our senses of humor meshed — and we were both itching to escape our respective lonely basements and make music with other humans. Ken’s drive and imagination on the drums became defining elements of the FJ sound.

Ken says: The tasks of a band member are many, whether it’s working on a musical idea for a song, the constant reworking and formation of a nearly completed song or, even better, working on a set list for a gig. But the creating of a song, a sound or a style, lyrically and musically, is a collective joy and fulfillment that aspiring musicians hope to achieve.

I think I can speak for all members of the Fashion Jungle: We experienced all this.

Here’s an example. In 1983, I couldn’t rehearse for several weeks due to a mishap I suffered at a company barbecue in Westbrook. I was playing a game of pepper — a warmup exercise where a batter hits a softball back to a gloved fielder in rapid succession. The batter, my boss, was a little too enthusiastic — he got aggressive with his swings and swatted a ball back to me that hit my gloved hand and fractured my thumb.

I needed surgery and was out of commission for a month. The Fashion Jungle continued to meet weekly and started working on new material. The song being developed was Doug’s “Nothing To Say.” When I finally returned, the band had a basic structure for it in place. Doug and Steve played the song for me a couple of times and I started to get ideas for a beat. What was amazing was how quickly it coalesced into one of the best songs in the band’s repertoire and became a staple in our set list.

Those years together were some of the happiest in my life. I was working two part-time jobs, studying to complete a four-year college degree, having a steady supportive girlfriend, practicing and playing gigs around town. I was extremely busy and every day my schedule was different. Never the rote routine. The sense of purpose was gratifying and exciting!

My favorite FJ gig was at Zootz when we supplemented my drumming with a drum machine on a few songs. Steve, Doug and I successfully streamlined our music to connect the songs together, making ourselves sound more professional while adding a certain stage persona. It felt like we were creating a show and not just playing a regular gig. I think it was our best-received performance by fans and critics alike. [The show was “Dance Alert II,” a November 1987 benefit for Salvadoran refugees.]

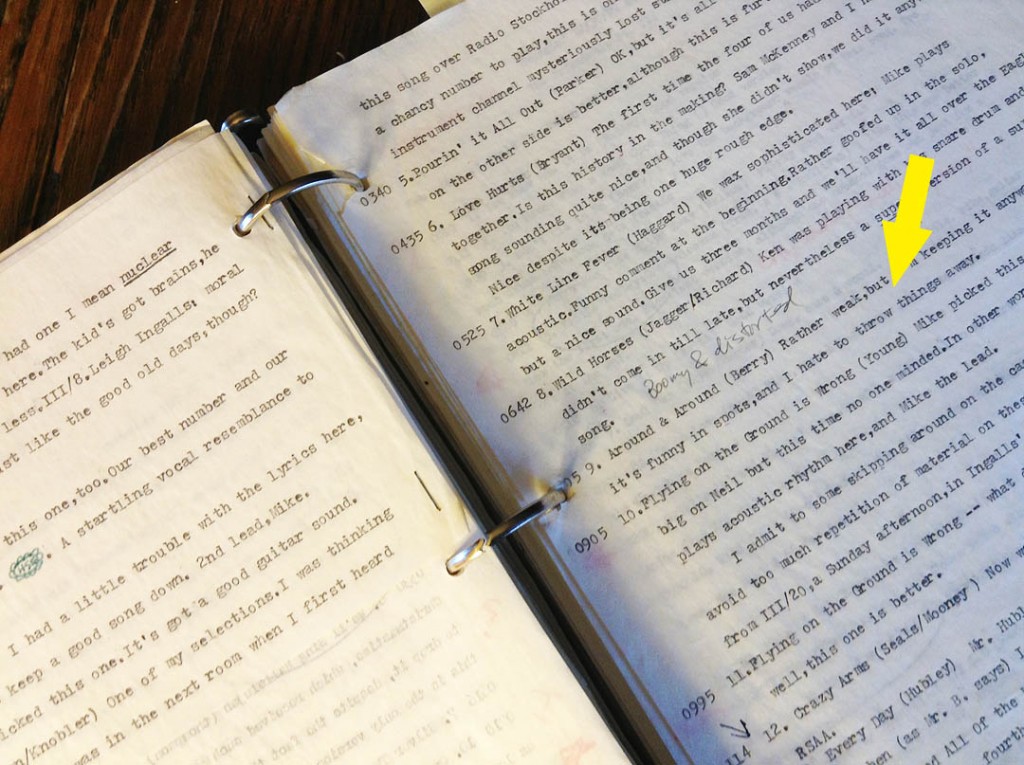

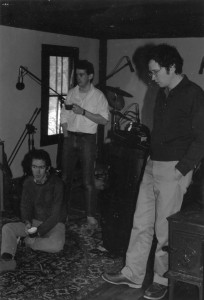

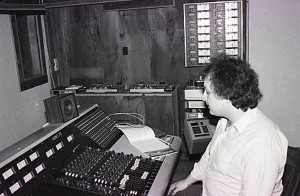

Other memories include recording the Six Songs cassette. We all felt pressure to record and distribute some of our original music. It was a hastily completed project, lasting about a day and a half. We each chipped in some dough to book the session. The atmosphere at the studio, the Outlook in Bethel, Maine, was very relaxed and ownership was very cooperative about working with us and suggesting ideas. All in all, a fun experience (despite the high-carb meals that were provided during our overnight stay. :))

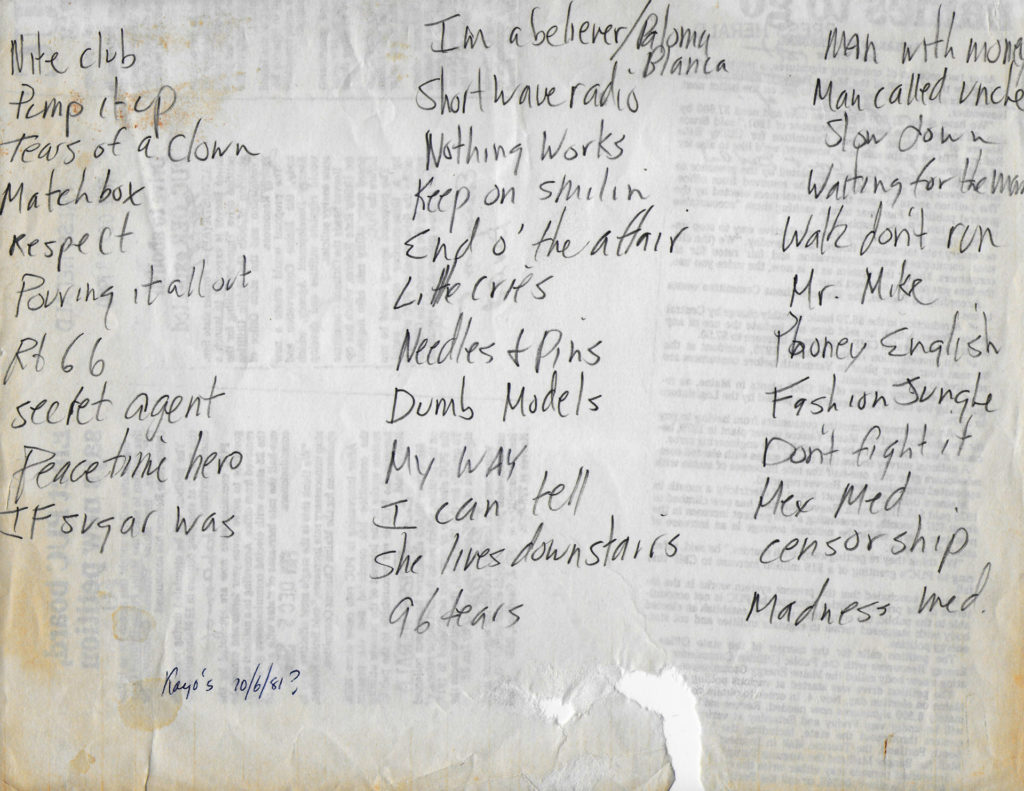

I always enjoyed opening for the Boston-based alternative bands that performed at Kayo’s. They were always friendly and genuinely offered their perspectives on the music scene in general and their support for us. Two bands in particular were Arms Akimbo and Zodio Doze — their members were very affable as they discussed the vibrant Boston scene and the best bands there.

Some of my favorite FJ songs, in no particular order, were:

“Nothing to Say” • “Phony English Accent” • “The End of the Affair” • “Little Cries” • “Final Words” • “Curious Attraction” • “Keep On Smiling”

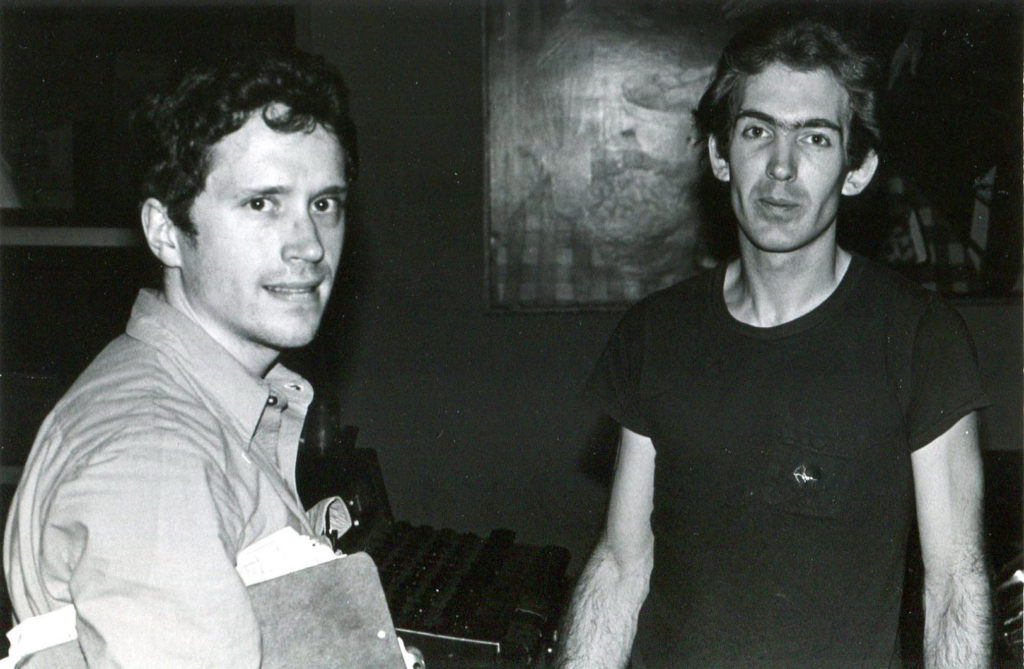

Mike Piscopo: Guitar, bass, organ, vocals, songwriting

Curley Howard Band (1977–78) / The Mirrors (1979–81) / The Fashion Jungle (1981)

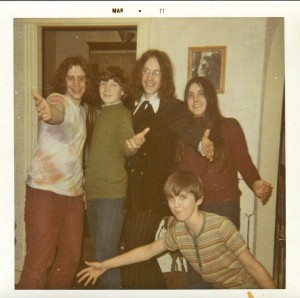

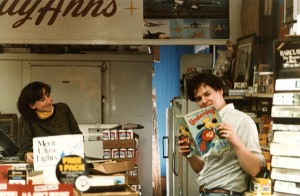

I knew Mike from “The Corner” — a convenience store in South Portland, Maine, called Patty Ann’s Superette. It was a busy social scene that spanned a wide age range. I’d been hanging around for years as a friend of the proprietors, the Stantons, and Mike was friends with Jeff Stanton’s youngest brother, Philip. Ken and I were looking for additional musicians, and Mike was learning guitar. Our first session consisted of two hours of “Green Onions.” The three of us plus bassist Andy Ingalls became the Curley Howard Band. Later, for The Mirrors, Mike added bass and organ to his portfolio. He moved to Texas in 1981.

Mike says: I don’t think the Fashion Jungle changed me personally, but I believe the structure we had — multiple instruments, vocals, etc. — really helped me musically. I was able to use that experience in a couple of bands I played with here in Texas.

And I enjoyed all the songs (or the ones I remember). I take great pride in playing them to my kids — all grown and accomplished musicians in their own form.

What does the band and that time of life represent to me now? Fond memories (although I really have to emphasize that the Curley Howard Band memories are my favorites!) Overall, I always felt the band was a tight-knit group of folks, probably because of the core history we had together. My favorite FJ gigs were the ones at Kayo’s — we were really tight [Sept. 16 and Oct. 6, 1981].

Overall, there is a special place in my mind for the time we spent making music — Curley Howard, The Mirrors, Karl Rossmann [the late-stage Mirrors], Fashion Jungle. Also, the friendships we had and still have, I believe, are priceless.

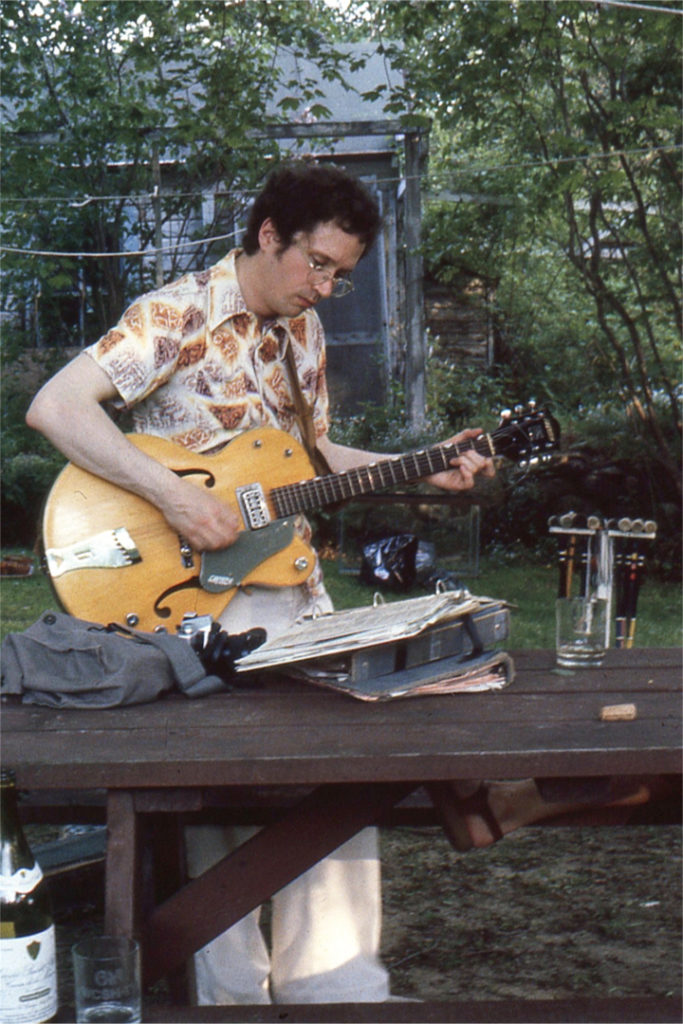

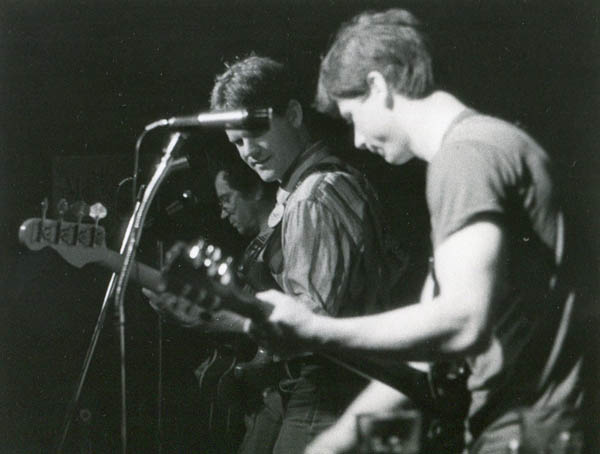

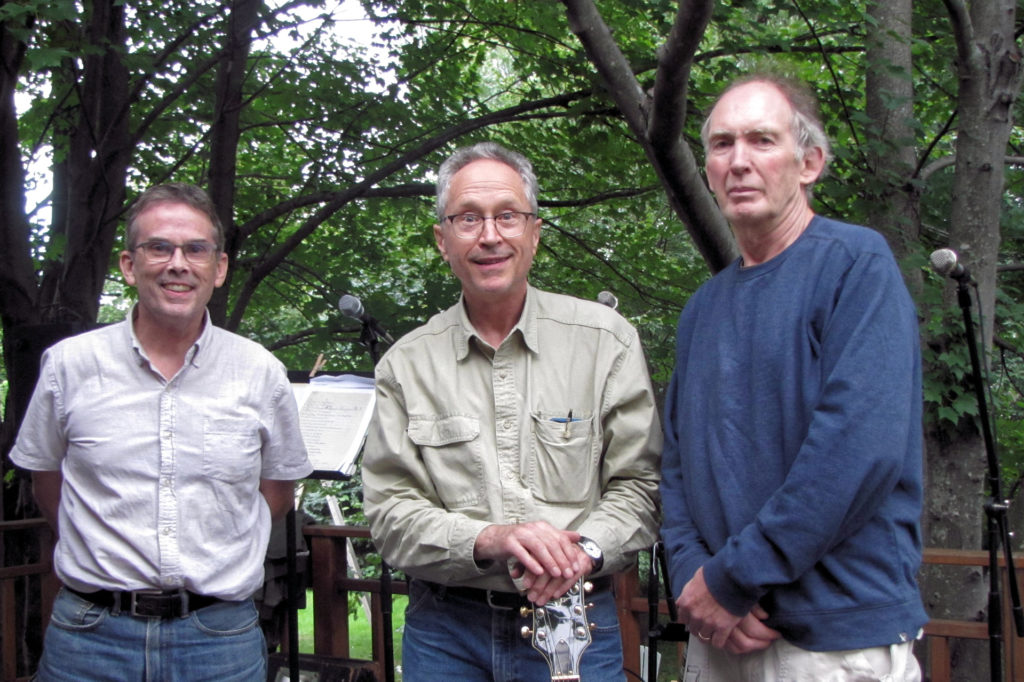

Jim Sullivan: Violin, guitar, bass, tenor sax, organ, vocals, songwriting

The Mirrors (1979–81) / The Fashion Jungle (1981–82)

The Curley Howard Band became The Mirrors with the departure of bassist Andy Ingalls and arrival of singer Christine Hanson. In response to an ad, Jim Sullivan joined us in early 1979 and turned out to be stunningly versatile — a good singer and songwriter, and an instrumentalist whose range encompassed fiddle, guitar, bass, keys and ultimately, tenor sax. Jim also brought professional savvy, which we sorely needed as a local agent heaped work on us, and a wicked sense of humor. Today Jim plays and writes music in The Barnyard Incident, an Americana band in Bethlehem, N.H.

Jim says: A bandmate during my time on the Boston Irish/Celtic circuit in the ’90s once said there are two types of bands: practicing bands and performing bands.

It was the transition from The Mirrors to the Fashion Jungle that gave me my first hint of that: Even though The Mirrors did perform songs we all liked, it seemed, in a way, more like a group of musicians taking turns in the spotlight than a cohesive unit.

The FJ, though, was the actualization of one musical trend of The Mirrors [punk and New Wave]. This focus seemed to gel more as a performing band, with everyone pulling the cart in the same direction. That did not mean we stayed in a box — just that one song had some thematic connection to the last, and led to some justified expectation for the next, giving the band its “sound.”

In addition, the FJ opened my eyes to the possibility that instead of just being a technician copying things, you could actually invent music with nothing limiting it but imagination. And I discovered at that time that I could stretch beyond stringed instruments, both banging out some tunes on the Farfisa rock organ, and taking up tenor sax and continuing to dabble in it for a couple more years. (But let’s face it: There’s something wrong with any instrument that needs a “spit valve”!)

Looking back at my all-too-short stint with the FJ (and with The Mirrors), as with all the bands of various genres I have been in, I am forever grateful that I was exposed to so much great music I might never have run into otherwise. I also took away from that era the importance of recording, both to capture a moment in time and to listen to and improve on my own playing.

On the originals front, one FJ song still on regular rotation in my mental spinning wheel is “Keep On Smiling,” mostly because of its sheer sonic power, and because I’m always easily seduced by organs of all types, from pipe to Hammond B3 to Farfisa.

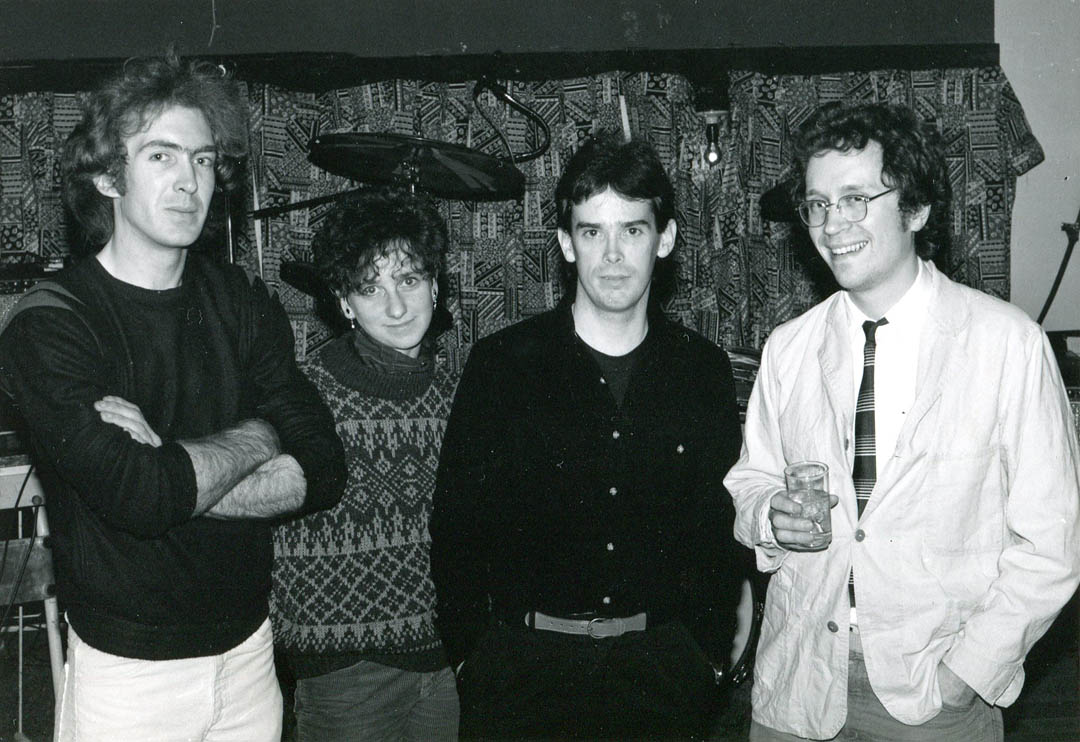

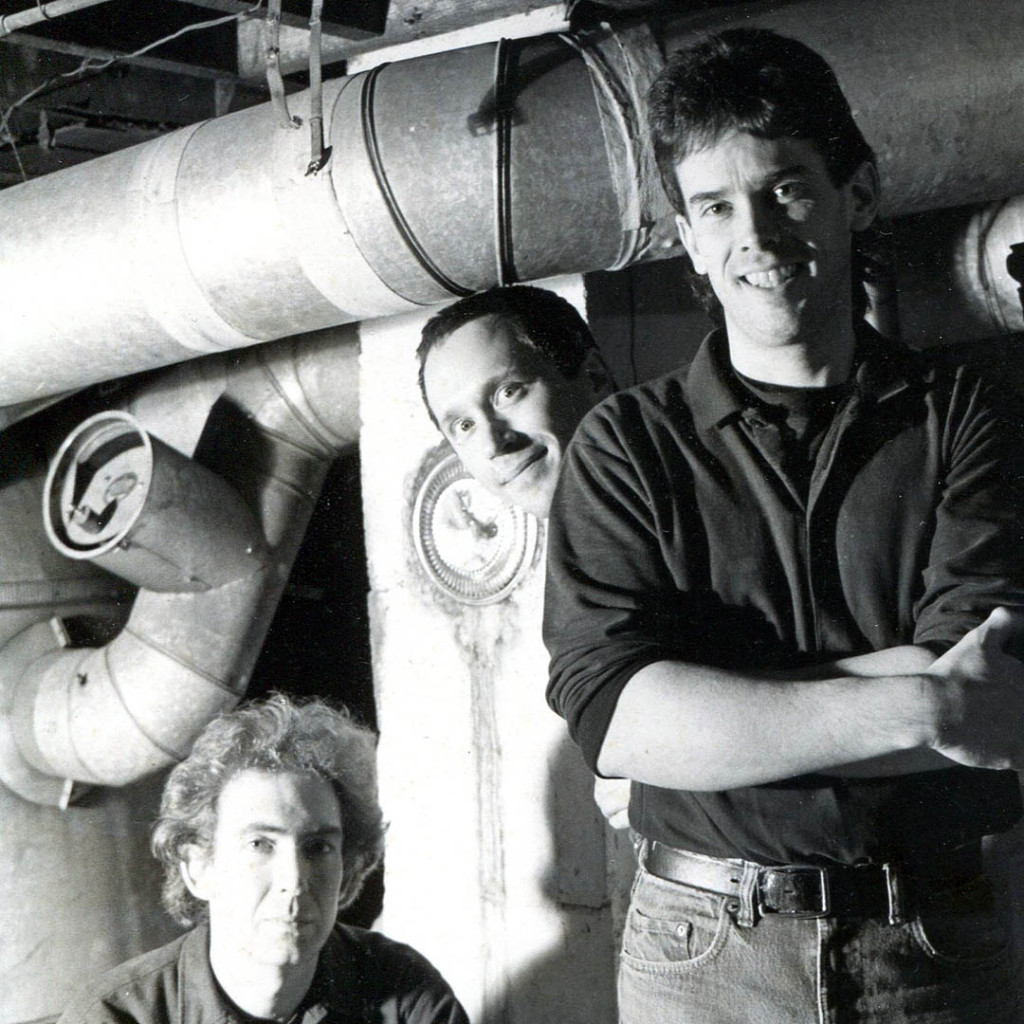

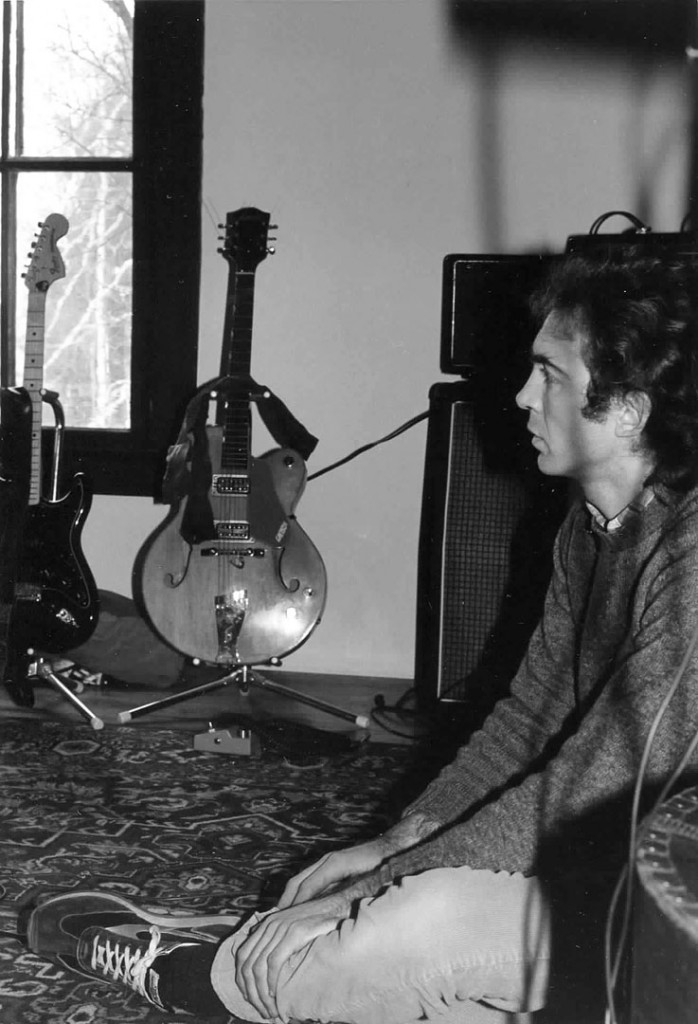

Steve Chapman: Bass, guitar, vocals, songwriting

The Fashion Jungle (1981–85, 1987–89) / The Cowlix (1989)

Steve joined the FJ in autumn 1981, as Mike departed for Texas and Jim moved to Boston to attend school. Steve brought a musical sophistication that, in his bass work, was key to our ability to succeed as a trio; and that in his songwriting, simply provided the FJ with some of its very best material.

Steve says: The Fashion Jungle is still a part of me after all this time and is the band I identify with the most. The other (10-plus) bands are pretty distant memories at this point, even those I was in after the FJ.

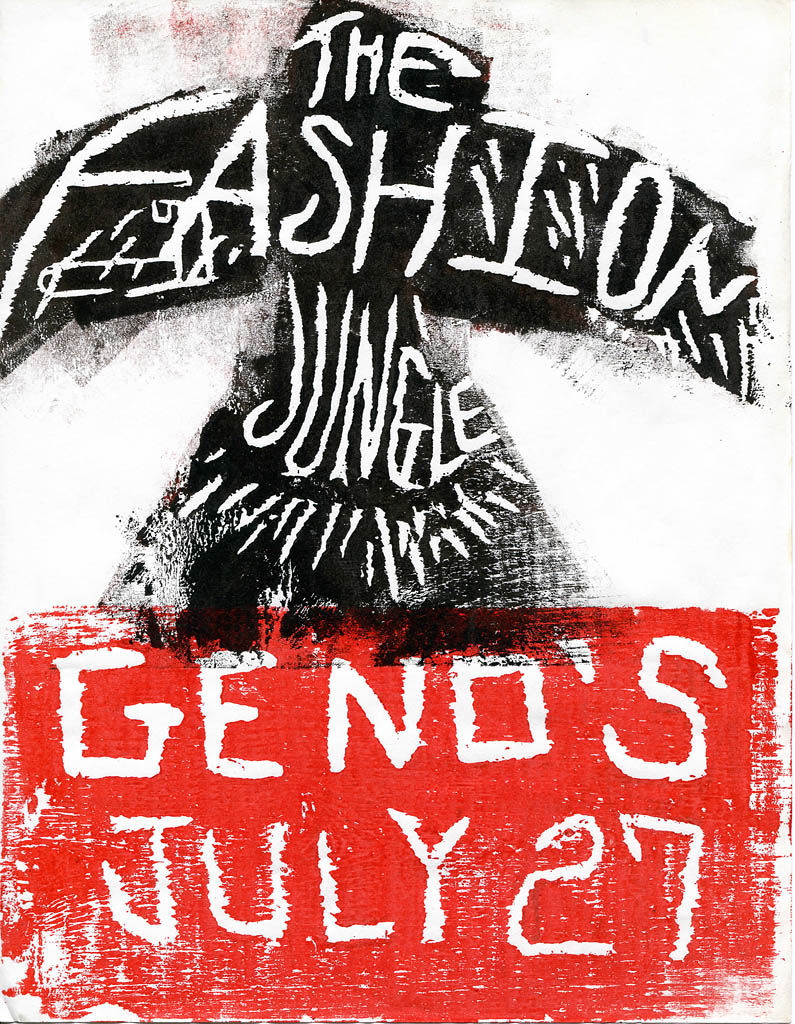

I’ve got to say that I quite enjoyed playing Geno’s, even though it was such a pit in those days — it was also a bonafide New Wave venue. Probably a bit like The Cavern Club, although I don’t think they had the same activities in the ladies room that Geno’s had.

Maybe my favorite FJ gig of all was the Maine Festival in Brunswick [in 1984. Steve, Ken and I also played the Portland edition in 1988]. That felt fairly significant. Another would be the Portland Expo concert where we hit the big time. I can still see David Minehan of The Neighborhoods slinking around in his trench coat waiting to go on — never letting anyone catch his eye. They were pretty good but we were better, in my humble opinion. [“Going To A Go Go,” Oct. 16, 1982. Also on the bill were The Pathetix, with Mike Piscopo’s brother Gary and future FJ keyboardist Kathren Torraca.]

I always felt our material was pretty strong and for the most part well-crafted. There were a few songs that we never came up with good arrangements for, but there was always an interesting nugget there. As for favorites, I could name any number of them (“Shortwave Radio,” “Entertainer,” “Groping for the Perfect Song,” “Curious Attraction,” “Nothing to Say,” “Peacetime Hero,” “Don’t Sell The Condo.”)

We had a lot of songs. Some of my favorites to play were “Breaker’s Remorse,” “Je t’aime” and, believe it or not, “Dumb Models.” We got bored with it, but it was about as heavy as it gets. We also had a nice selection of covers. I always liked playing Leonard Cohen’s “First We Take Manhattan.”

The FJ made me a much better bass player as time went by. I wasn’t doing much when we first got together and the band exposed me to a lot of music that I hadn’t been paying much attention to. It was a real period of growth for me as a musician.

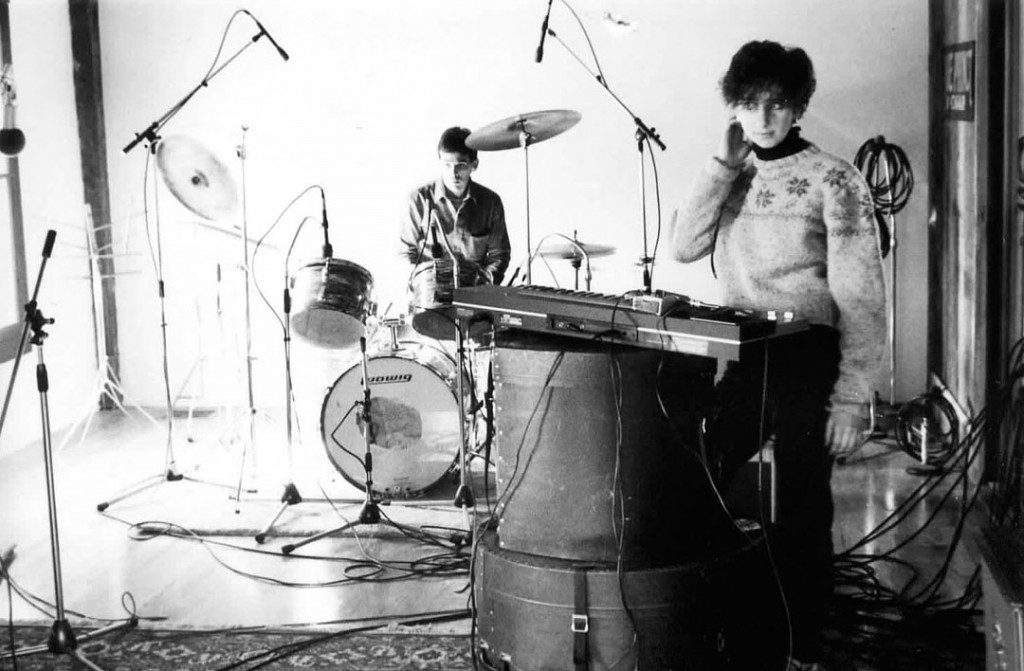

Kathren Torraca: Keyboards

The Fashion Jungle (1983–85)

With keyboardist Kat making it a quartet, the band reached a pinnacle of sonic richness — and local recognition — in 1983–84. Her synth textures and colors had a dramatic effect on the FJ, both expanding the types of material we could pull off and, perhaps more importantly, bringing the romanticism in our music fully to the fore. A teenager when she first joined us, Kat was also the best kind of smart aleck.

Kat says: I’m not sure that my time with the Fashion Jungle changed me, but it was one of the most fun periods of time that I look back upon. I was always a bit nervous before each gig but at the end, it felt great — no matter how it went! I loved our energy and watching the dance floor fill over the course of the night — most nights….

I was so young! It was a time of learning, maturing, exploring and lots of really great fun. Looking back, I was very excited, and lucky really, to be playing with such talented friends and getting those experiences — practices, recording, gigs, pre-gig prep and post-gig–high hanging out. And the opportunities to meet and work with other talented local musicians, and to have been an active part of the music scene in 1980s Portland.

I remember audiences singing our original songs. No particular gig stands out in detail for me, but there are a couple that I remember more than others. There was one at Kayo’s — the feeling I took from it is of a particularly packed audience and great dancing. And there were many nights at Geno’s where we had good audiences and lots of energy.

I remember going out for breakfast after gigs, practicing in Ben and Hattie Hubley’s basement, and watching you all drink Black Velvet. And Alden and his van, being on the cover of Sweet Potato and printing FJ T-shirts in my basement. [Kathren designed an early FJ shirt that featured a leg in camouflage hose wearing a bright red stiletto heel.]

Dan Knight: Bass, vocals, songwriting

The Fashion Jungle (1985)

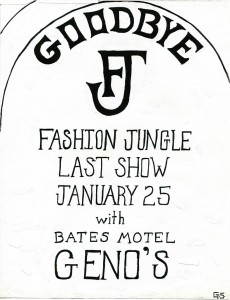

After one last Geno’s show in Dec. 1984 — which I don’t recall at all — the Chapman-Torraca edition of the FJ, sometimes also featuring Jim Sullivan, continued to rehearse into early 1985. And then we were done, as Steve, like Jim before him, had moved to Boston, where he was studying software coding and had met his wife-to-be, Jeri Kane. But Ken and I were still game, and placed an ad in the Sweet Potato for musicians. We heard from, and hired, one: bassist Dan Knight. And by July the FJ was back in business, at least for another six months.

Dan says: In the mid-’80s, after three years of alleged study up north at the University of Maine, I’d had enough of playing music in dorm rooms and left school for the big city — Portland.

I originally hooked up with a psychedelic garage band centered around the Geno’s scene when it was in its original location, on Brown Street. I got a job driving a school van and discovered that I had a not-necessarily-healthy fondness for the British-style ale being served at the old Three Dollar Dewey’s. The psych band didn’t last long — and it was right about then that I had the obligatory hopeless romance, resulting in a broken heart that I nursed for years. Good Times.

I’d heard the name Fashion Jungle around town. They were of a previous generation when the place for cool bands was the original Downtown Lounge — and the Portland waterfront was still dangerous. I saw their ad for a bass player in the Sweet Potato, another relic of that era. It was the local music paper and everybody read it.

Whatever the Fashion Jungle’s past incarnations, at that moment it was now basically down to two, Ken and Doug. They gave me a cassette tape of their original material. I heard echoes of Talking Heads and Elvis Costello, but the Fashion Jungle was definitely its own thing. I played along with the tape as best I could, tried to get the gist, and then had an audition. I apparently passed.

The original songs were genuinely unique and the covers were unusual, including Frank Sinatra and Johnny Cash. Rock bands weren’t doing that at the time. We even learned some Motown songs to play at a wedding. I believe my run in the Jungle lasted only six months.

I went back to school, finishing up at the University of Southern Maine. I still play music and, sometimes on a rainy day, still nurse that broken heart.

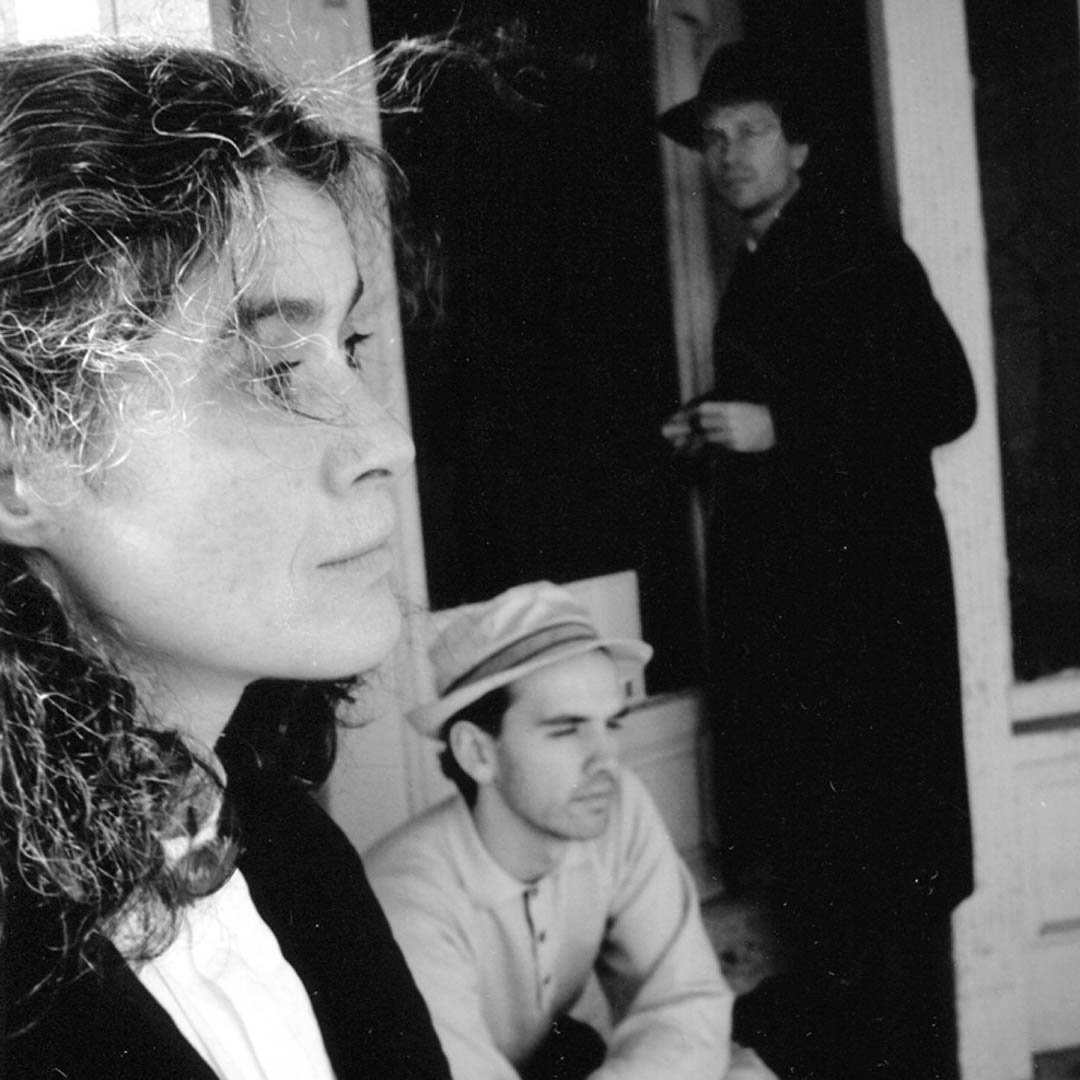

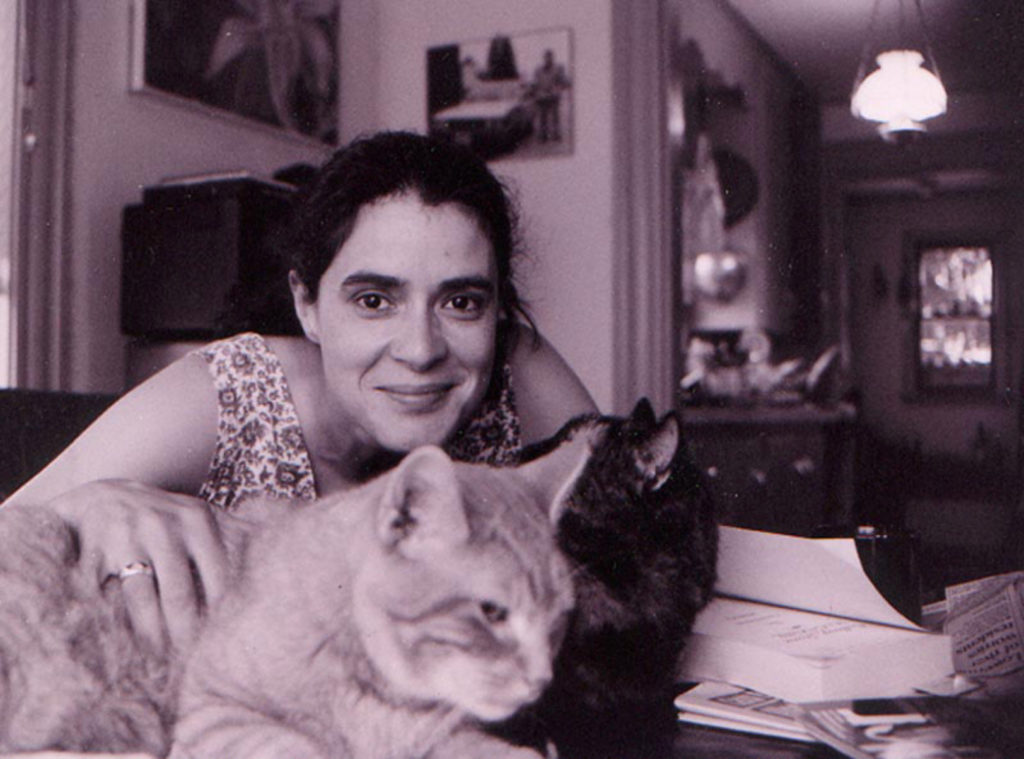

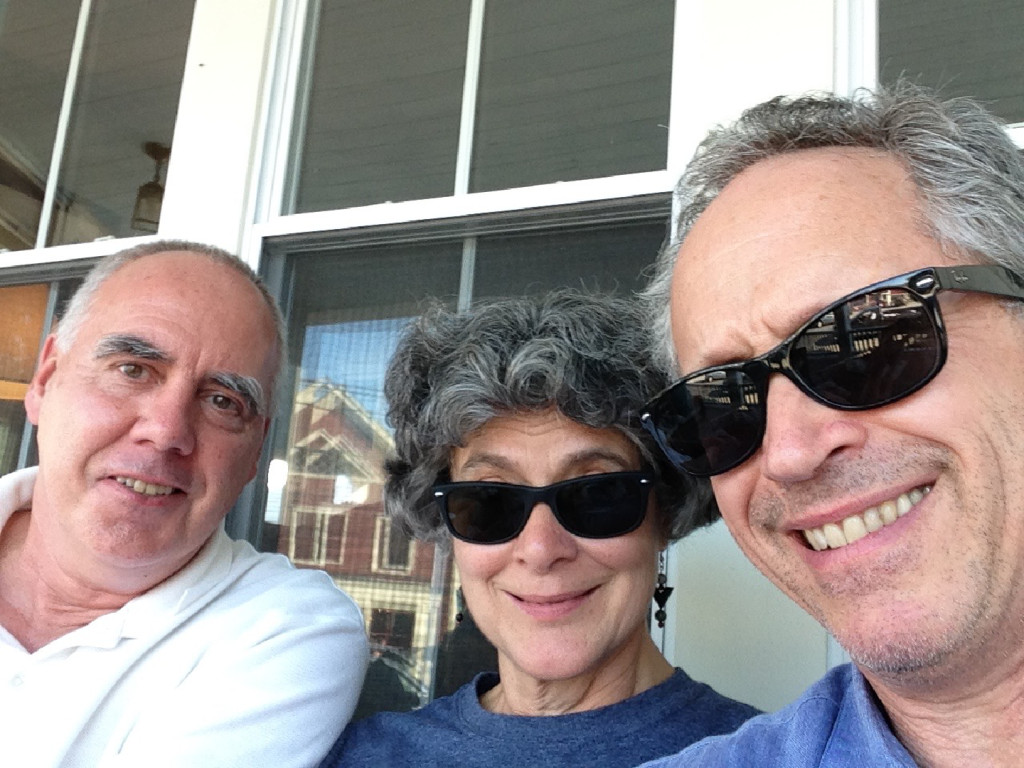

Gretchen Schaefer: Road manager, staff artist

The Fashion Jungle (1981–89) / As guitarist, bassist, singer: The Cowlix (1989–94) / The Boarders (1994–96) / Howling Turbines (1997–2004) / Day for Night (2007–)

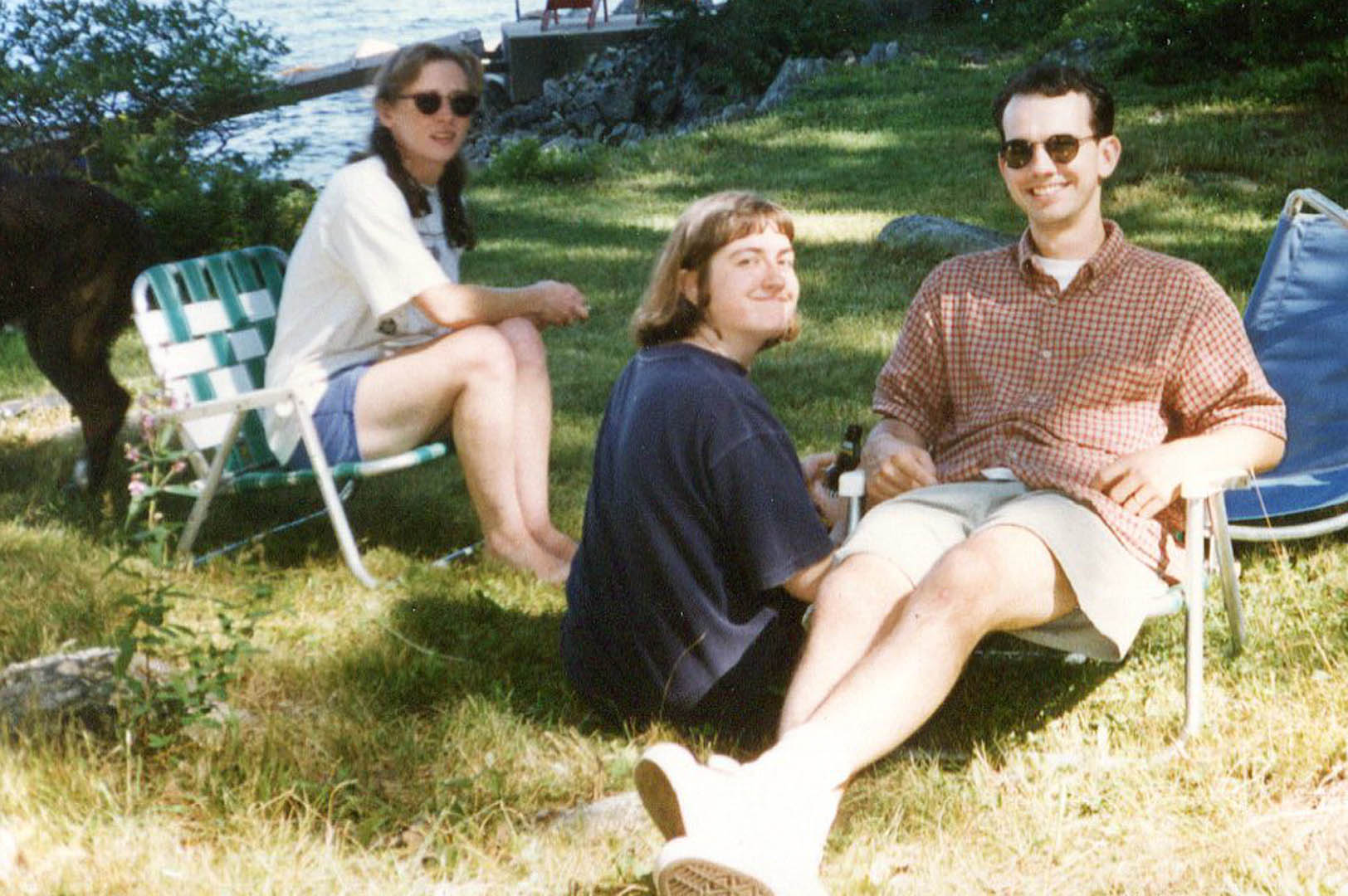

Gretchen and I met in a philosophy of art class at the University of Southern Maine in autumn 1981, at the time the original FJ quartet was coming apart. (So the FJ’s is not the only 40th anniversary worth celebrating in 2021.)

As our relationship grew, she became integral to the band as a roadie and contributing artist for FJ promotional efforts. In the FJ’s final months, we decided to open for ourselves under a different name and play classic country and rock, and Gretchen joined us on stage playing rhythm guitar. She and I have made music together ever since.

Gretchen says: The first gig I saw the Fashion Jungle play was at Kayo’s [Oct. 6, 1981], and I remember just being really impressed with the band. I didn’t really know you at the time, and people talk a lot of crap, so I did not have high expectations at all — I was basically thinking it was going to be terrible.

I was so surprised at how put together the band was, how professional it seemed, just how well-rehearsed and smooth your sound was. It was a thing — you really projected an image and a sound that was cohesive, and I found that very impressive.

The other thing that struck me was that you all could play on different instruments with some fluidity and authority. It never had occurred to me that people would be able to do that. I always figured in a band, everybody had their one instrument and that’s what they would play.

The original group seemed like this crazy mashup, but it all cohered. It seemed — not really circusy, but really exciting and kind of wild. That changed when it was just you and Ken and Steve. That was a whole different iteration of the band. I was around more for that, to see it shaping and building up, but it seemed more serious in a way than those early gigs.

With the Fashion Jungle, I was an observer mostly. I had a privileged position in that I was very close to the band, I was at a lot of rehearsals, recording sessions and gigs.

I loved it. It was exciting. I’d never been close to a band before — a real band that performed out. Just observing how bands acted and interacted with one another, and how it all came together and how gigs were gotten and played. And bands were such a big part of what we were all thinking about growing up.

Being able to do some of the artwork was something I really liked. It allowed me to participate in my own artistic way. I was trying to respond to the band, to take in your ideas and meld them with my own vision. I like that commission process a lot, assembling ideas together into a coherent whole. [An established mosaic artist now, doing business as Great Blue Mosaic, Gretchen designed posters, T-shirts and the cover image for the Six Songs audiocassette.]

That time of life seemed like the culmination of my youth. I’d had a lot of different experiences before that, but it seemed like a high point of the young part of my life, not only our relationship building but just being part of that milieu.

So many of the gigs blend together — all those gigs at Geno’s where I was tending the door with Alden. [Alden Bodwell had been a roadie and friend since the Curley Howard days. He passed away in December 2019.] There were certain fans that I would see at every gig. That little blonde skateboard girl — she looked too young to be there, for sure. She’d have a skateboard with her, she clearly was out of bounds, but she came to so many gigs.

Then there was that tall guy with the bushy, sandy hair who danced. A really bouncy dancer. And people like Seth Berner, Will Jackson, you would just see a lot at the gigs, they really liked the FJ.

Geno’s was gritty, like totally gritty. Then the Marble Bar was less gritty. The 1984 Maine Festival was the cool pinnacle, and Zootz seemed like this New York, groovy vibe, which was fun.

It was interesting to hear those same songs over and over at different gigs, and how they would change. They’d be faster or slower, the mood often would change with how you would emphasize the lyrics. It was interesting to me to hear that because I had not heard performances repeatedly like that.

“Shortwave Radio” was always very striking to me. It’s a really percussive song, and I thought that was interesting. That was probably a huge standout for me. “Je t’aime” is a great song, so sophisticated. Those Ken songs, like “Dumb Models” — I thought that was so funny. It was so apropos, and it was such an unapologetically boy view of things. The stripper song, “Entertainer.”

I always liked the postmortem after the gigs. We’d bring the equipment back, and there’d always be that little period of just hanging around for a few minutes, talking it over in the dark. It would be late at night. There was always the rating system: Ken would say, “Well, how do you think it went?” It was a scale of 1 to 10. Everybody would have to give their number.

And the whole divvying up of the money after a gig. Alden would always want to refuse his share, and you’d all have to force him to take some.

The Fashion Jungle as a band changed so much over time. It was interesting to see the rotating personnel piece of it. It had never occurred to me that there would be this changing cast of characters, and that somebody would continue to try to put it together again — “Are we going to actually try to replace that person? Are we just going to function as we are?” — and how that drove the music and how you presented yourselves.

Reading about other bands afterward, it made a lot more sense to me, having seen it firsthand, how difficult it is to keep a group of people all going in the same direction for very long, especially people at a really volatile time of life. You were all in that young adult time, where people were making pretty big life decisions that affected the band.

Jeff Stanton: Road manager, staff photographer-videographer

The Fashion Jungle (1981–89) / The Cowlix (1989–94) / The Boarders (1994–96) / Howling Turbines (1997–2004) / Day for Night (2007–)

Living and working at Patty Ann’s Superette, Jeff and his siblings attracted friends of diverse ages to the Stanton family’s variety store. The roots of several bands, including the FJ, were set deep in this fertile social scene, which produced the Curley Howard Band and its successors, as well as the Pathetix and the Foreign Students. Featuring the latter two bands and the Mirrors (1980) and the FJ (1981), “Corner Night” concerts paid tribute to this South Portland phenomenon. Jeff has amassed an important photographic record of these bands, their descendants and their times.

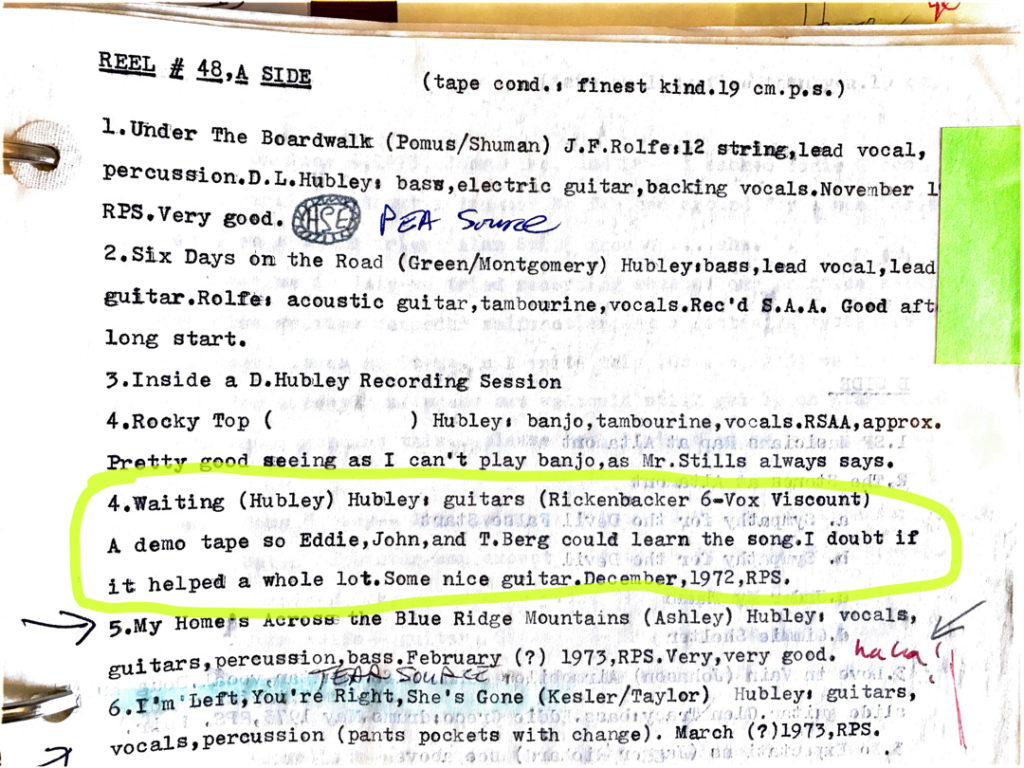

Jeff says: In connecting with friends of my siblings in the neighborhood, I was, I guess, an observer or a witness to several individuals’ musical development. I would go back as far as Truck Farm — you and John Rolfe and Tom Hansen. That was the seeds in the soil there. Things were germinating then. [Truck Farm, 1971–72, was my first performing band, another decadal milestone for 2021. John Rolfe went on to form the Foreign Students and The Luxembourgs.] I even remember it when I was away at school — the people who played guitar and how others would gather around.

One of the things that I really appreciate about the whole experience was the social connections I made. It was good for me. The bonds that were created then, they’ve endured. We’ve grown as friends.

And being part of that creative enterprise was cool. That goes back to that whole Corner experience, where there was a whole nexus, network, of activity, and people coming and going. It made my social interaction very easy, because I didn’t have to get outside myself — everybody was coming there, for whatever reason. It was a neighborhood vortex. That circle of interaction and creative expression was very satisfying.

I did make some effort to document visually, in photographs, what was happening. And then not being a musical participant, I wanted to contribute some way, so being able to lug equipment, I was certainly capable of doing that. That made me feel I was part of it.

There’s one memory I have from Geno’s where I was talking to a girl, and we were talking about the band. This always stuck with me — she said “crucial,” the music being crucial, or “essential.” It was just this attractive girl I was talking to, and I didn’t really know her. I don’t know if she knew you guys, so it was just interesting to hear a stranger comment about the music, which I thought was cool.

I enjoy live performances now, but I often didn’t go to hear other local bands. I think as a social activity, the FJ actually got me to go out to hear music, probably because I’d been introduced to it — I was desensitized, a little bit more comfortable with it.

I remember once hearing somebody being disappointed by a concert because it didn’t sound like the album. But part of the appeal of live music is that it’s an ephemeral expression, and the result of everything that’s happened to that point. And it’s appealing to hear the same songs live more than once.

If you had gone only once, and they played really fast, “really fast” would be the memory. But there are other times when there’s a different vibe. I know it’s probably different for band members who rehearse and rehearse, and that’s why one has to appreciate when they can bring some freshness to it.

Besides, sometimes “too fast” is just what you need.

I reread some Basement posts, and I’ve been listening to FJ music over the course of things. It’s interesting how listening to it brings this well of emotion back up. It was a high point, it was something that brought things together, got us together.

Whenever I go by there now, heading out to Cape Elizabeth and seeing the Corner, I don’t see a bunch of kids hanging around. I don’t see guitarists standing up against the side of the building, or people sitting on the side, or skateboarding in the parking lot there. I sometimes think of that time and wonder, if I had approached life differently and decided to set out on my own and not stayed at the store — well, things would be a lot different. I would be very interested and curious to know what different things would have sprouted for everybody else, too.

The FJ wove some vibrant threads, tones, and textures into the fabric of my experiences at that period — nights at Jim’s and Geno’s were always an event. I don’t know what the warp and woof of the fabric of my being would be without the various FJ interactions and influences. I imagine the patterns would be different.

More from the Fashion Jungle on Bandcamp and in Notes From A Basement

- See the complete Notes from a Basement posts featuring the Fashion Jungle, sorted by oldest first or newest first.

- See my discography at Bandcamp, which includes 12 albums by the FJ.

- See way too many images including several FJ galleries.

And here’s a blow-by-blow listing of chapters in the FJ story, in Notes and on Bandcamp, starting with the oldest (note that some titles may diverge):

- Faster, Louder, More Fun: The Fashion Jungle Arrives: Notes | Bandcamp

- Fashion Jungle: Late for the Party: Notes | Bandcamp

- Standing on the Corner . . . Suitcase in My Hand: Notes | Bandcamp

- Wheels Within Wheels: Chapman Joins the Fashion Jungle: Notes | Bandcamp

- Three in a Match, or the Jungle at Jim’s: Notes | Bandcamp

- Dial K for Keys: Torraca Joins the Fashion Jungle: Notes | Bandcamp

- Little Cries: Fashion Jungle in Studio, Part I: Notes | Bandcamp

- Six Songs: Fashion Jungle in Studio, Part II: Notes | Bandcamp

- Fashion Jungle: End of the Affair: Notes | Bandcamp

- Fashion Jungle: Knights and Free-lances: Notes | Bandcamp

- Fashion Jungle: Veterans’ Club: Notes | Bandcamp

- Fashion Jungle: Audio Out — Video In: Notes | Bandcamp

- Together Again: Videos of the Fashion Jungle at ’20 Years of a Basement’: Notes | Bandcamp

- Other Voices: The Fashion Jungle, 40 Years Later: Notes | Bandcamp (album planned for summer 2021)

Notes from a Basement text and D. Hubley photos copyright © 2012–2021 by Douglas L. Hubley. All rights reserved.