Day for Night: World Domination

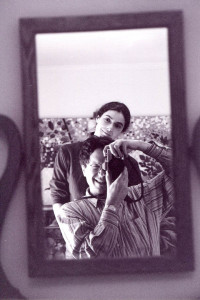

Gretchen Schaefer and Doug Hubley look skeptical in a 2008 publicity image. Photo by Kodak self-timer / Hubley Archives.

Hear Day for Night perform Charlie and Ira Louvin’s “When I Stop Dreaming” in 2018.

I admit that for a band that plays

four to eight public performances a year, and considers the high end of that range hectic, it may be grandiose to state that we ever “arrived.”

But if Day for Night did arrive, it was in 2008. And to my mind, the time of arrival was a private party that we played that October.

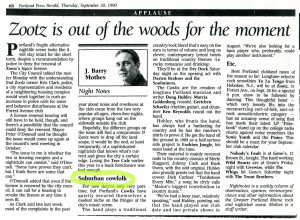

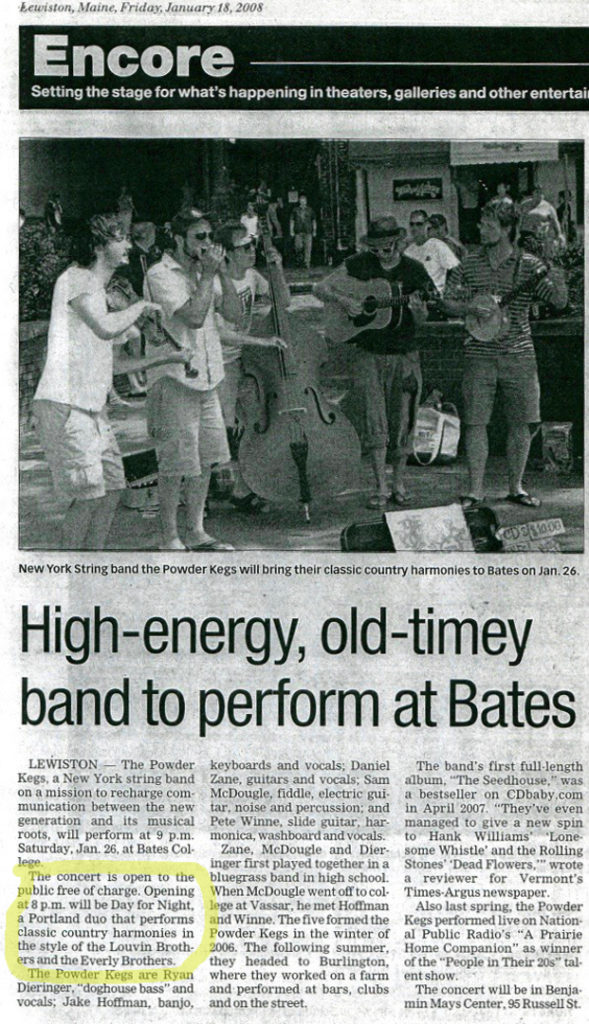

Day for Night rates a whole paragraph in the Sun Journal’s advance for the Jan. 2008 Powder Kegs gig. Hubley Archives.

It was an afternoon-to-evening bash in a big attractive loft in Brunswick. Gretchen Schaefer and I were joined by our friends Steve Chapman, on bass, and drummer Willy Thurston, and we called the foursome the Day for Night Orchestra.

A number of other acts were scheduled to play, most of them combinations and permutations of a group of people that, taken altogether, were the big band headlining the show. The ringleader was an impolite fellow who didn’t seem to want us there.

He fussed about this and was rude about that. We stowed our guitar cases in the wrong places at least twice. The coleslaw that we made from homegrown cabbage and brought for the potluck meal was an object of disdain.

Still and all, we were businesslike, played pretty well, put our hearts into it, connected with the listeners, and were polite to the man who didn’t want us there — who went on to confirm it, once the crowd started showing some enthusiasm, by running up to the mic and cutting off our set. His party, after all.

I nevertheless ended up feeling good about the whole thing. That show came late in a year of performances in diverse settings, from a concert at Bates College to the Cornish Apple Festival. It was a year in which we got established as Day for Night, finding our footing as an acoustic country duo after two decades in electric bands.

We worked the fussy man’s birthday party with a combination of aplomb and musical focus that told me that we’d found that footing (albeit, at the risk of contradicting my premise, as an acoustic duo with an electric rhythm section). If we walked away irritated with the birthday boy, we were very satisfied at how we handled his party.

I felt, in short, that we’d arrived.

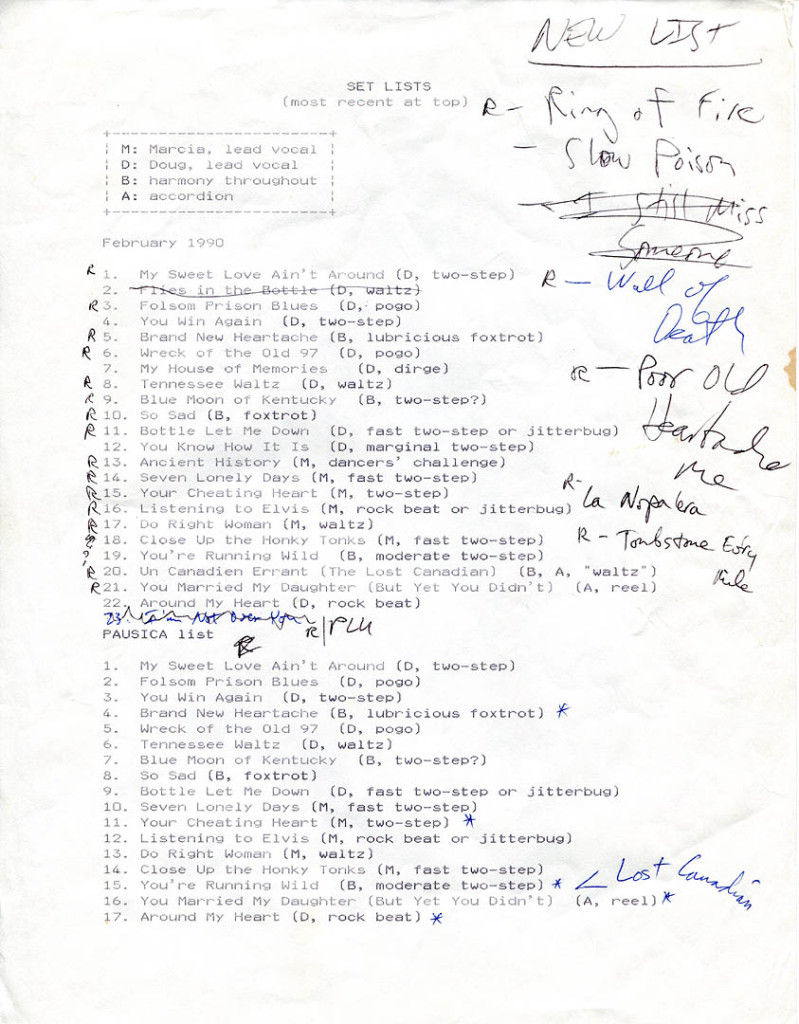

Yes, tape

As Gretchen and I started feeling more confident about Day for Night, I fired up — as I do pretty much reflexively at this late date — the single-cylinder publicity machine.

Top priority on that front was obtaining demo-quality recordings. Steve rolled the tape (yes, tape. Four-track tape!) for sessions in July 2007 and July 2008.

The 2007 demo landed us a short string of dates at the Frog & Turtle Gastropub, in Westbrook, where we were discouraged by the crash and clatter from the kitchen, directly behind us; but encouraged by Johnny Cash on the house sound system and the generosity of owner James Tranchemontagne.

The 2007 demo also helped get us a gig that shines on in my memory: a spot at Bates College, where I work, opening for a band of hipsters called the Powder Kegs. They were billed as an Americana band, which D4N also is, sort of. So I threw myself at the feet of the event sponsor, the student radio station.

The performance took place in January 2008. The night was frigid and starry, the campus walkways were glare ice.

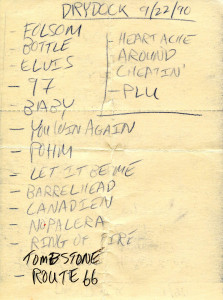

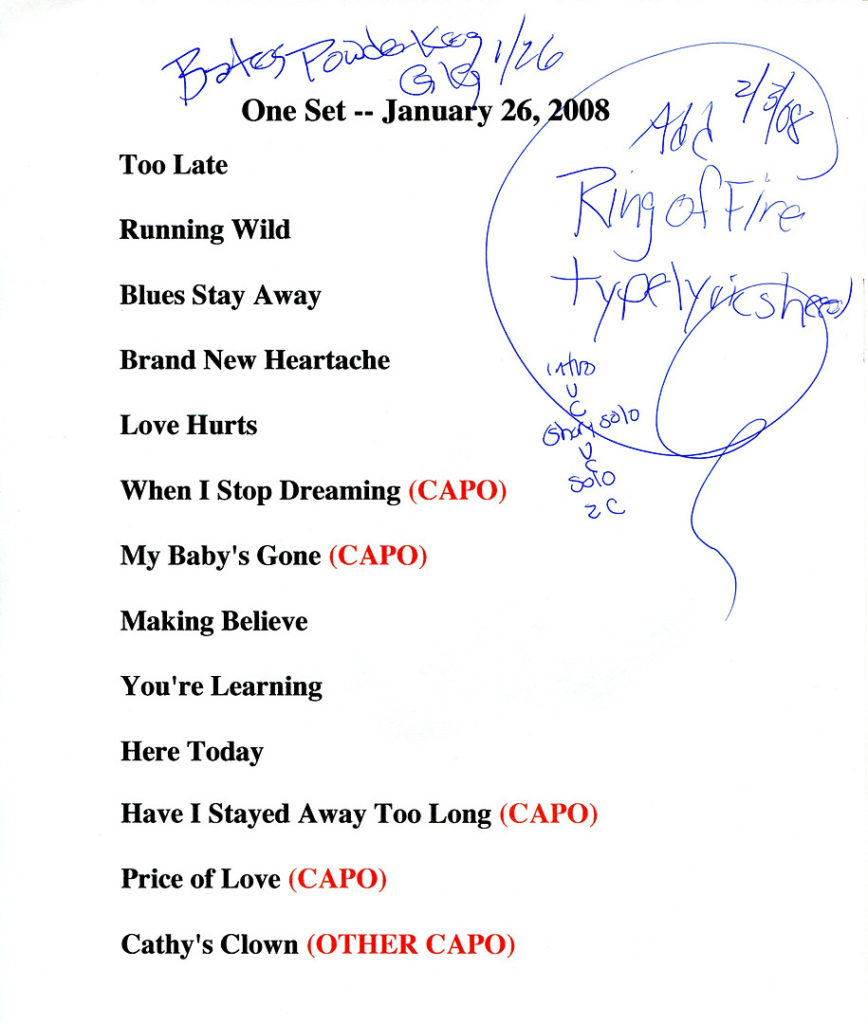

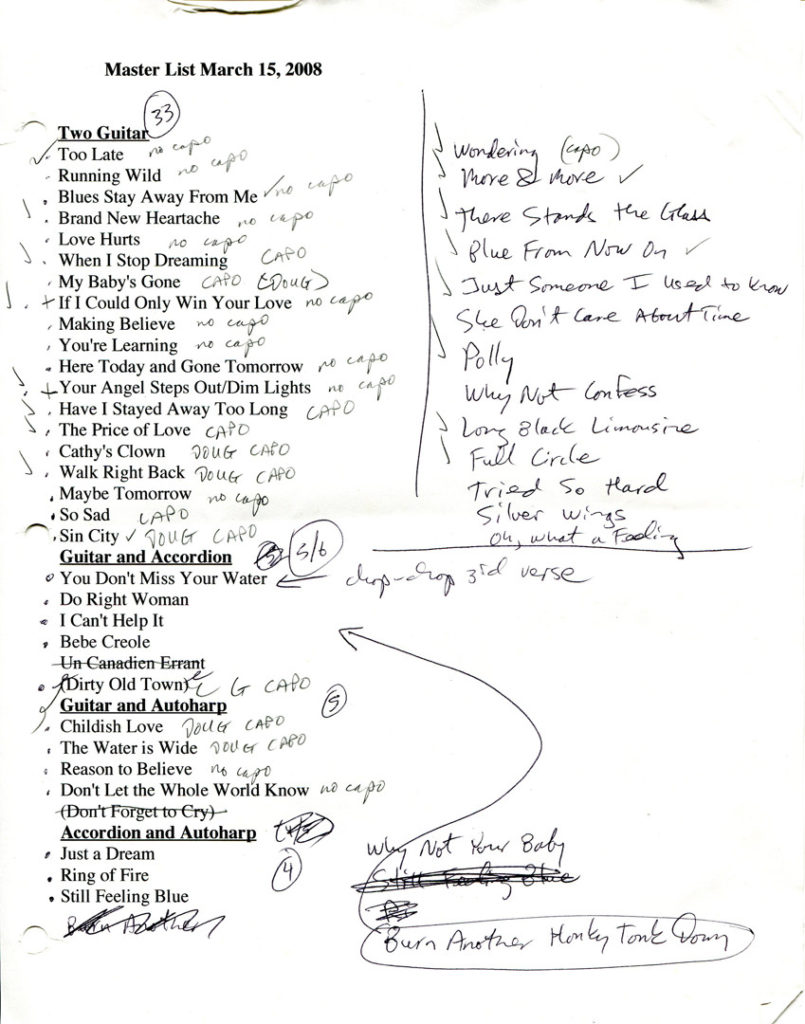

The setlist for Day for Night’s opening spot for the Powder Kegs (where are they now?) at Bates College in January 2008. We had learned every song here from the Louvin Brothers, Everly Brothers, or Gram Parsons and Emmylou Harris. We would soon begin broadening our catalog. Hubley Archives.

The publicity machine had coughed out a news release that, through the Lewiston Sun Journal, attracted an old-school country audience of 20 or 30. It was plain that those folks, people in their 50s and 60s and 70s, from Minot and Livermore Falls and Greene, weren’t there for the Powder Kegs. (After our set, one of those listeners talked to us at length about WWVA, the legendary West Virginia country radio station. I was flattered that he would associate Day for Night with the home of the “Jamboree.”)

We eschewed our usual multi-instrumental assault and stuck to two guitars. The sound operator knew his stuff, gave us perfect onstage sound, brought out our best. The locals really liked us — we could see and feel their attention. The Powder Kegs crowd hadn’t gotten there yet.

Okay, I’m romanticizing, but I recall that performance as one of Day for Night’s best-ever (even though I messed up the lyrics to “Cathy’s Clown”).

I incorporated the 2008 demo CD (yes, CD), which even had a picture of us on the label, into a proper press kit (albeit without any sort of treat like the key-pins that the Boarders had distributed).

Yes, four years into the Facebook era, and I was packing press kits in manila envelopes. I still keep a few of the kits around while I look for a museum that will take them.

One October evening we tromped around Portland with a sack of press kits. The kit failed to seduce Empire and Space Gallery, but did work some kind of magic with Blue, the Portland, Maine, nightspot where we went on to play a few times a year between 2008 and 2014. And, as I have noted in an earlier post, 2008 was the year we began our long run at the Cornish Apple Festival.

From the top, Day for Night’s first, second and current business cards. Gretchen designed the rooster crowing at the moon. Hubley Archives.

Hungry catalog

Simultaneous with the search for gigs in 2008 was a greed for new material.

A previous post describes how a select few artists — the Louvin Brothers, Everly Brothers, Gram Parsons — helped us set our musical compass. In fact, of the 32 songs we performed at a representative D4N date in May 2008, six came from the Everlys, seven from Parsons (including two that he learned from the Everlys) and 11 from the Louvins.

But soon enough, we’d mined out most of the appealing Louvins-Everlys-Parsons repertoire and were eyeing all the other country musicians out there. (Not literally “all.” Setting aside the songs I write, we knew from the start that c. 1938–1978 was our happy place in country music, and with a couple of exceptions we’ve haven’t ventured out of it. This approach was validated by many wasted hours spent watching the primetime soap opera Nashville.)

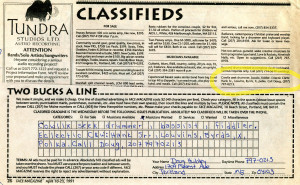

The Day for Night repertoire in mid-2008. Note our early lineup at left — Everlys, Louvins, too many instruments — and the new material at right, all arranged for two guitars and reflecting a wider range of influences. Hubley Archives.

Exacerbating the repertoire hunger was a sort of feedback loop: The more country we got, the less appropriate a lot of our older material became, so we were shedding material as fast as we added it. It was only inevitable that we’d bust out of our little repertory corral.

I dug deeper into artists I’d always liked. An example is the late Gene Clark, the former Byrd whose songwriting may be the color that’s deepest-dyed in my own compositions.

Harold Eugene Clark — Gene Clark — whose awkwardnesses with lyrics and music somehow translated into a higher order of pathos and poeticism. Clark, who was too passive to stop Crosby from taking the Gretsch away from him, but not too passive to drive a vintage Ferrari; whose two Columbia albums with the Byrds were the band’s best; and who was the only Byrd to bother bringing good original material to the quintet’s 1973 reunion LP.

Clark, not a pure country artist in style, but one of the purest in spirit.

In 2008, in a kind of fever, we learned his “Tried So Hard,” “She Don’t Care About Time,” “Why Not Your Baby” (on autoharp and accordion), “Full Circle Song” and “Polly.” The last two remain in our active repertoire. Later came “I Remember the Railroad.”

If Gene Clark material was a fad for us that year, the George Jones catalog was, and remains, a long-term project. We have claimed a few — “Beneath Still Waters” is one of our strongest numbers — but between the sui generis superiority of Jones’ singing and the tinniness of much of his material, it’s hard to find Jones numbers that suit both our abilities and our fussy tastes.

Gretchen was not a Buck Owens fan. (Fair enough. I mean, “Tiger by the Tail,” really? “Where Does the Good Times Go?” Obviously they doesn’t go where there’s grammar.) But he sure could sing, and in 2009 we picked up “Under Your Spell Again,” which remains a high point in our set.

We also started exploring artists we’d known about forever but hadn’t looked into. From Webb Pierce we got “There Stands the Glass,” “Wondering” and “More and More,” the latter two boasting lovely lead vocals by Gretchen Schaefer.

From Wynn Stewart came “The Long Black Limousine” (and “Playboy” is still on my to-do list).

I’d heard “Dim Lights, Thick Smoke (and Loud, Loud Music)” by the Flying Burrito Brothers, but we weren’t moved to learn it till we heard it by the Maddox Brothers and Rose. We combine “Dim Lights” with George Jones’ “Your Angel Steps Out of Heaven” in our so-called Cheating Housewives medley.

And, when I got home from work one day in 2008, Gretchen surprised me by launching into “Just Someone I Used to Know,” the brilliant Jack Clement number that we heard by Dolly and Porter.

In 2009, the “Trains” episode of Bob Dylan’s splendid “Theme Time Radio Hour” on SiriusXM gave us two hot tickets: Jimmy Martin’s “Mr. Engineer” and Johnny Cash’s “Train of Love.” (Ah, those Monday nights sitting in the Pontiac Vibe, listening to Bobby.)

And on it went, and on it goes. (Anyone for the Bailes Brothers?) 2008 was as big as the big time gets for Day for Night: four to eight gigs a year, from the Frog & Turtle to Blue to Andy’s Old Port Pub, from the Cornish Apple Festival to the Cornish Inn, from the Last House on the Left to the launch party for a friend’s hot dog cart on the banks of the Presumpscot River.

So we arrived and so here we are. For a couple of aging introverts, it could be worse.